This is our wrap up chapter. We recap how the brain works (see, it wasn’t that complicated after all). We acknowledge the stuff we still don’t understand (detailed circuitry, functional dynamics). We emphasise some of the themes that emerged (themes like: what is one thing in psychology is many things in the brain; where you are is what you do as a way to think about content-specific processing mechanisms; and that evolution does not pre-specify banana detectors in the brain to emphasise that the central nervous system starts out as a generalist and adapts to experience). And then we go back to our opening puzzles, and run through which properties of the brain explain some of the more idiosyncratic ways our minds work. Why is it, for instance, that I can forget what the capital of Hungary is, but not that I’m afraid of spiders? Now we can tell you. And here are some final wrap up points:

- One of the themes of the book is the challenge of linking entities we have invoked to explain the mind (memory, attention, personality, and so forth) with how the brain works. We used the motto, what is one thing in psychology is many things in the brain. This one-to-many relationship may be one reason why the mind can seem to work in different ways in different contexts – because a particular context engages a different subset of the mechanisms that deliver the psychological process.

- Now our journey is complete, you may have spotted another complication that makes things even harder for the psychologist: there may be more than one thing in the brain doing approximately the same thing in terms of psychological function. Because of the pathway that evolution followed, we can see layering of similar functions from evolutionarily older and newer structures (newer often being an issue of scaling, with self-organisation allowing new functionality in the latterly upscaled parts); and then emergent division of labour between these systems. Here were two examples that leapt out at us: the basal ganglia, anterior cingulate, and prefrontal cortex each have a contribution to choice-of-behaviour. And second, the thalamus and prefrontal cortex each have a contribution to attentional selection of perceptual information. No one ever said the link between mind and brain was going to be easy!

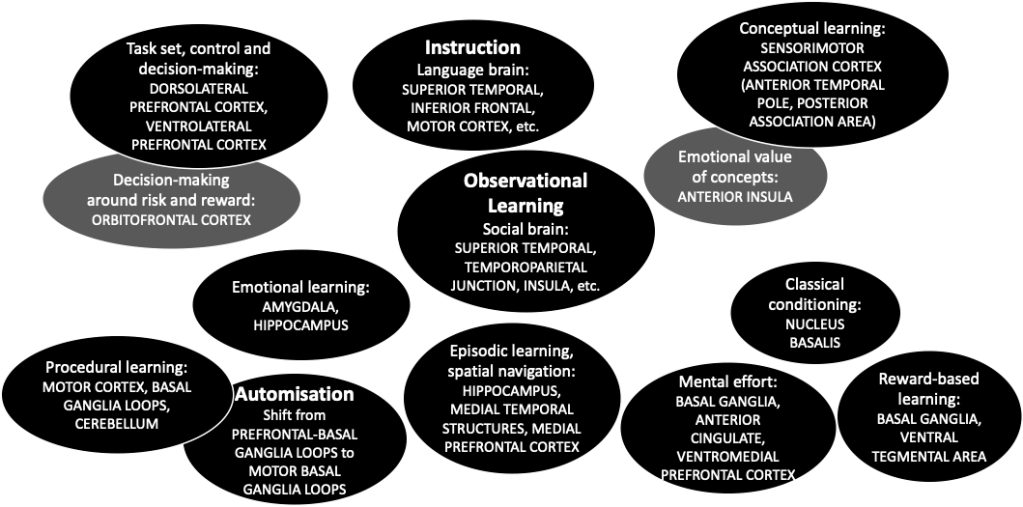

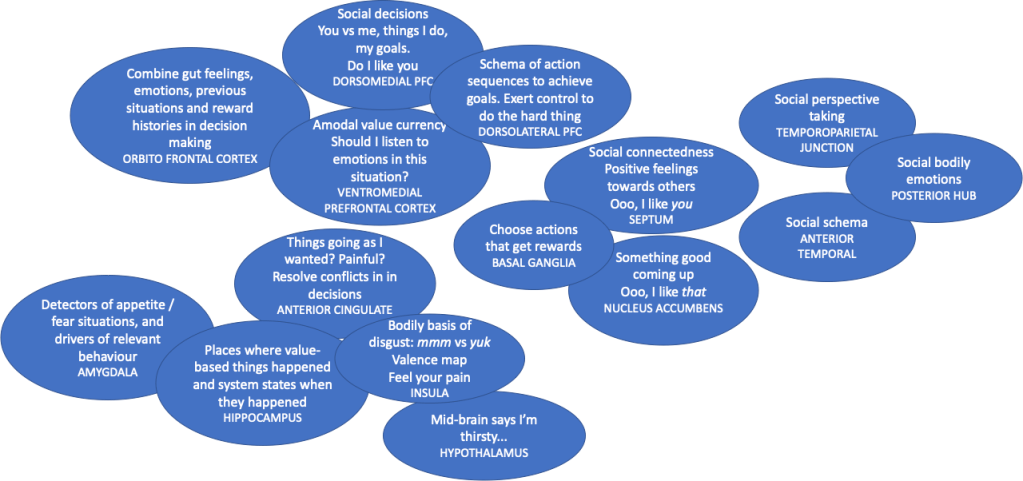

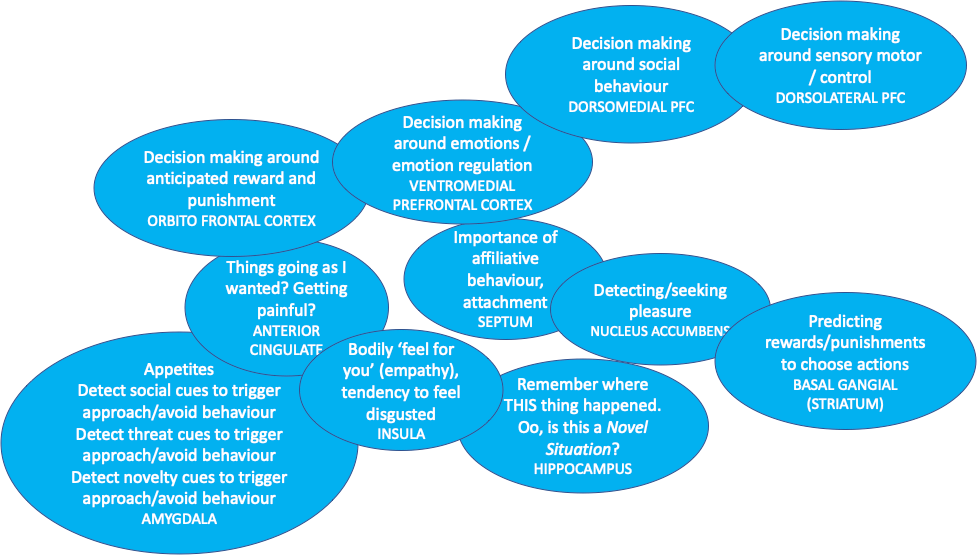

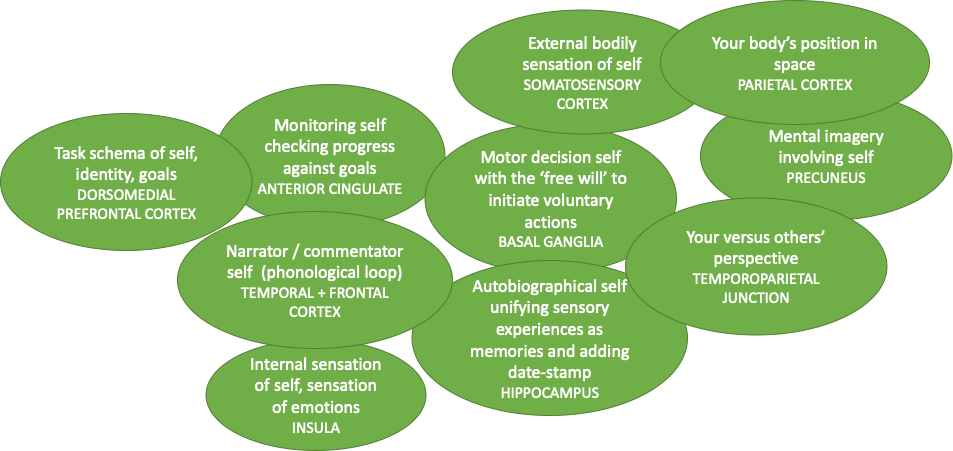

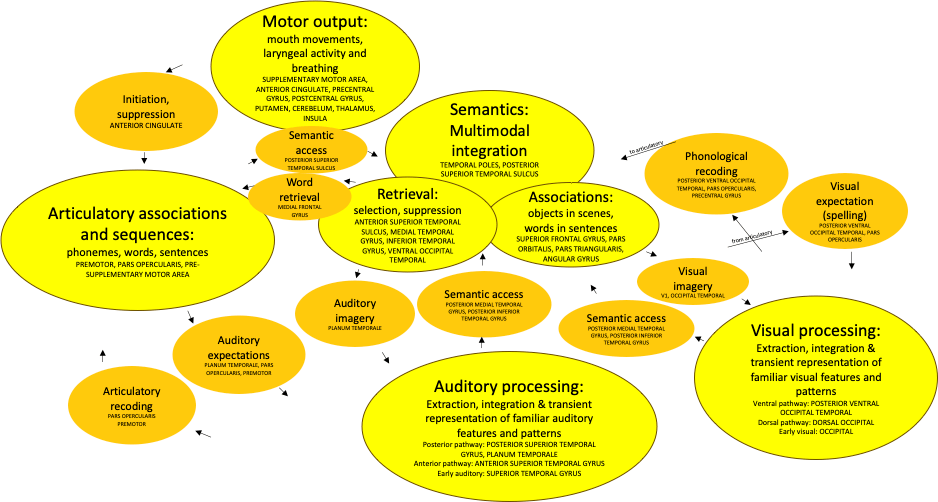

- As we’ve gone along, we have introduced ‘bubble diagrams’, to show the various brain systems involved in producing behaviours linked to psychological concepts, typically involving a combination of content-specific systems, parts of the modulatory system, the reward-sensitive action selection system, the emotional limbic system, and the motor smoothing cerebellar system. We’ll finish by bringing these diagrams together here. Respectively, these show the brain mechanisms linked to learning, value, personality, the self, language, and attention. Together, they perhaps begin to give a sense of how the concepts within psychology – invoked to explain and predict high-level, whole-organism behaviour – map to the predominantly sensorimotor concerns of the brain, its multiple circuits developed to process other people, its pursuit of emotional goals and rewards, and its endeavours to make decisions around situations of uncertainty and risk. Thanks for reading!

- Learning:

- Value:

- Systems tuned differently to generate different personalities:

- The self:

- Language (we had to distinguish mechanisms and pathways on this one!):

- Attention:

And finally, if you’ve just finished reading the book, you may have been startled by last line, a confession that erudite authors such as ourselves sometimes struggle to spell the word ‘acquiesce’. Readers, joking aside, we can assure you that we do know how to spell acquiesce. We have even once or twice managed to correctly spell the word ‘acquiescence’. We of course employ the well-known English spelling rule ‘i before e, even if there’s cs and ss and qs all over the place, like, you know, you could have 3 cs in a word and i might still come before e but other times it doesn’t.’ It is the language of Shakespeare.