In this chapter, we introduce important aspects of evolutionary theory for understanding how the brain works. For example, many of the basic properties of cells, neurons, and brains are common across a lot of species. And when we look across mammals, although brains vary in size, there are no new bits of the brain for specific complex behaviours observed in a given species. It seems that mammals all use pretty much the same plan for growing their brains, with the knobs set a bit differently. So: bats don’t have a new part of the brain for their specialism of echolocation; humans don’t have a new part of the brain for their specialism of language. This begs the question: how do you get species-specific behaviours for all the different mammalian species if their brains have similar structures (albeit scaled differently)? Why do sheep flock while wolves hunt? Why do moles dig and bats fly? Why do pigs forage for truffles and people post selfies? We provides the answers.

- ‘Back in 1973, a wise person once said that nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. The same holds for the brain.‘ -The wise person was evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No

- We were slightly tired of evolutionary diagrams always showing the ascent of ‘man’. What about women? We asked Scarlet to sketch an alternative for fun, so she included a fashion model as the culmination of homo sapiens rather than a businessman. But the final cartoon was a little too racy for us to include in the book! Here it is:

- ‘First, many of the basic properties of cells, neurons, and brains are common across a lot of species. They are, in the terminology of the field, highly conserved.’ Here’s Barbara Finlay’s list of what properties of the mammalian brain are highly conserved, that is, consistent across species: “There’s one big aspect of conservation that seems to me to be missing because of the general emphasis there has been on tinkering and modification. This is the general body and brain plan (macro, 450 million years ago) and fundamental mechanisms that are also conserved (meso-micro), like the list of fundamental neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, excitation, inhibition (analog) to action potential (digital), Hebbian learning, lateral inhibition/ sparse coding, perhaps some network features we don’t fully understand yet” (personal communication).

- ‘The functions of neurons have taken eons to evolve.‘ – For more on where the functionality of neurons probably came from: Kristan, W. B. (2016). Early evolution of neurons. Current Biology, 26, R949-54. “Surprisingly, single-celled organisms not only have voltage-gated channels but also have many of the genes for presumed synapse-specific molecules, such as enzymes for producing and releasing transmitters and structural proteins that produce postsynaptic responses to the transmitter” … “A reasonable guess is that voltage-gated channels functioned to regulate intracellular ions and water of the ancestral prokaryotes, to keep them from bursting in the hypotonic water that was their environment, and were only later specialized for communication” … “Three kinds of gated channels probably evolved independently: voltage-gated channels, stretch-gated channels, and ligand-gated channels (probably used by animals initially for finding algae and bacteria by sensing their exuded chemicals)” … “It is a reasonable guess that most neurons in most animals are evolutionarily derived from epithelial [skin] cells.” Chemical signalling probably evolved from sensory cells, electrical signalling from motor cells (p. 953, col.1).

- ‘Within mammals, you see similar structures from rats to cats to chimpanzees to humans‘ – Common brain regions across vertebrates: Cesario, J., Johnson, D. J., Eisthen, H. L. (2020). Your brain is not an onion with a tiny reptile inside. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(3), 255-60. Figure 1 caption: “All vertebrates possess the same basic brain regions, here divided into the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. Colouring is arbitrary but illustrates that the same brain regions evolve in form; large divisions have not been added over the course of vertebrate evolution”.

- You can spot some differences in the split between amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, suggesting that the type of neurons that make up the cortex (the outer layer of the brain) look like an innovation for mammals: Woych J, Ortega Gurrola A, Deryckere A, Jaeger ECB, Gumnit E, Merello G, Gu J, Joven Araus A, Leigh ND, Yun M, Simon A, Tosches MA. Cell-type profiling in salamanders identifies innovations in vertebrate forebrain evolution. Science. 2022 Sep 2;377(6610):eabp9186. doi: 10.1126/science.abp9186. Epub 2022 Sep 2. PMID: 36048957.

- ‘The Brain-Builder-5000‘ – Yes, knob #3 is a metaphor for the genetic controls on brain development! Each knob would correspond to the concerted actions of 1000s of genes influencing the developmental process. But we’re not introducing genetics just yet. It is currently unknown what the full set of genes would be that constitute the brain-making machine (minimally, we’d expect multiple genes to be involved in setting each of the controls, even if the controls are few). In principle, this set of genes is hard to uncover, because it’s a highly conserved plan: these genes don’t vary between people, their precise function is too important. The only way to find out what these genes do is to mutate them one by one in an animal model. Even then, some of the genes have backups which take over if a target gene is mutated, making it look like the gene does nothing.

- For a better idea on the redundancy in genetic mechanisms, see the work on the yeast genome, where most of the 5000 genes seem to ‘do nothing’ if you mutate them individually – i.e., there is no effect on developmental outcome. The same sized patch of mould grows on your jam (or in the petri dish). As Michael Costanzo said in his 2016 paper summarising this work: “A study on yeast ten years ago found only one in five genes were essential to the yeast’s survival. Since then, research has found a fraction of our genes are essential in human cells too – most genes are ‘buffered’ to protect the cell from mutations and environmental stresses. This makes it difficult when trying to work out which genes are responsible for certain phenotypes, particularly when interactions occur”. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3808143/The-chatter-inside-cells-maps-genes-interact-help-fight-inherited-diseases.html. Costanzo M, et al. A global genetic interaction network maps a wiring diagram of cellular function. Science. 2016 Sep 23;353(6306):aaf1420. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1420.)

- Nevertheless, state-of-the-art genomics has begun to identify which genetic variants may have been selected to produce different primate brain structures and functions, by comparing variations in the genomes across 52 primate species, with brains spanning 3cm3 in size to 1300cm3 in size. This analysis has identified genes involved in influencing both brain size and neurotransmitter function, so the knobs on the Brain-Builder-5000 may yet swing into view! Shao Y, Zhou L, Li F, Zhao L, Zhang BL, Shao F, Chen JW, Chen CY, Bi X, Zhuang XL, Zhu HL, Hu J, Sun Z, Li X, Wang D, Rivas-González I, Wang S, Wang YM, Chen W, Li G, Lu HM, Liu Y, Kuderna LFK, Farh KK, Fan PF, Yu L, Li M, Liu ZJ, Tiley GP, Yoder AD, Roos C, Hayakawa T, Marques-Bonet T, Rogers J, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Schierup MH, Yao YG, Zhang YP, Wang W, Qi XG, Zhang G, Wu DD. Phylogenomic analyses provide insights into primate evolution. Science. 2023 Jun 2;380(6648):913-924. doi: 10.1126/science.abn6919. Epub 2023 Jun 1. PMID: 37262173. See especially Figure 4 and p.919.

- Why does our Brain-Builder-5000 have only THREE KNOBS, you may ask? Of course, the genetic controls on brain development are vastly more complicated, but we gave the Brain-Builder-5000 just three knobs to reflect a statistical analysis of variation in the relative size of brain regions across species, as well as just within humans. This analysis used a technique called principal components analysis to find out how many main dimensions the sizes of bits of the brain seemed to vary over. For example, for the cross-species analysis: Finlay, Hinz, Darlington 2011, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0344, p.2114 commented: “Three features predominate in mammalian brain scaling: high intercorrelation of structure volumes, distinct allometric scaling for each structure and relative independence of the olfactory – limbic system from the rest of the brain. At this point, we can consider nine major taxonomic groups, using the brain divisions employed in the original analyses of Stephan & Manolescu. The first two principal components of volume variation account for 99.01 per cent of the total volume variation in this set of 160 mammals. The first factor is highly loaded on the cortex, cerebellum, diencephalon and mesencephalon, accounting for 96.47 per cent of the total variance. The second principal component loads most highly on the olfactory bulb, and next on olfactory cortex, hippocampus, septum and subicular cortices, accounting for 2.61 per cent of the variance. In addition, a third component relates body size independently to the sizes of the medulla and cerebellum—this factor is small, but significant, and has been reported in other kinds of analyses. Finally, each brain division has a distinct allometry [method of scaling], with each brain subdivision increasing at a different slope as brain volume increases overall. In particular, the neocortex and cerebellum scale with absolute brain volume at high slopes so that very large brains become disproportionately composed of these two structures”. So that’s where the three knobs came from.

- This work has also drilled down to assess variation in the sizes of bits of the brain just within humans, see: Charvet, Darlington & Finlay 2013, Doi:10.1159/000345940. The Charvet paper also highlights that the limbic system might have partly independent variation in humans from the rest of the brain, which is relevant for later in Chapter 8 where we argue that intelligence and personality may vary independently: Charvet et al. comment: “We performed a principal component analysis to capture the structure of variation between brain region volumes in humans. Such an analysis shows that the first, second and third principal components account for 49.42, 14.04 and 9.76% of the total variation, respectively. The first component loads highly on the isocortex, mesencephalon, medulla, diencephalon, cerebellum and striatum. The second principal component loads on limbic structures such as the olfactory cortex, the septum and to a lesser extent the subicular cortices. The third component loads highly on the hippocampus and subicular cortices. These findings show that the limbic structure volumes are in part dissociable from remaining brain region volumes in our sample of human brains.” Still three knobs, though!

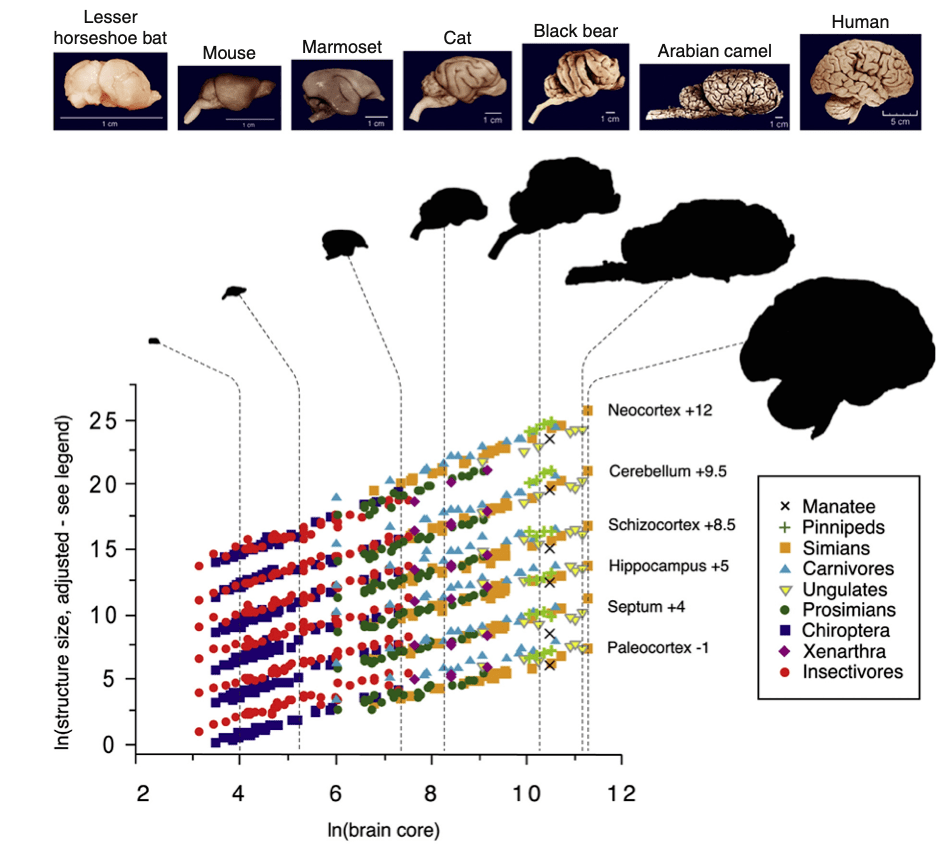

- The book contains a sketch of the data, but here’s the relevant plot from Charvet et al. (2013) showing the cross-species scaling of brain parts against whole brain size. (This is a colour version created for: Finlay, B.L., Uchiyama, R., 2017. The Timing of Brain Maturation, Early Experience, and the Human Social Niche. In: Kaas, J (ed.), Evolution of Nervous Systems 2e. vol. 3, pp. 123–148. Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN: 9780128040423). Note, this is a log-log plot to make the trajectories look more linear; and that the intercepts have been separated so the lines don’t lie on top of each other (the amount each line has been shifted up is shown next to the label, e.g., +12 next to neocortex). These tweaks are for clarity: this main point of the plot is to show that relationships hold across species and the lines for each part have different gradients. It suggests a common brain building plan, where the apparent differences in size of, say, the neocortex across species, are just a consequence of the different rate of scaling of each part within the plan, as you scale up the whole size.

- What’s the explanation for the different scaling? It turns out that the bits that develop last when building a brain are the ones that get disproportionately larger as you scale the whole thing. This in turn is due to the consequence of letting progenitor cells (the ones that will shortly produce the neurons that construct the brain structure) carry on sub-dividing for a bit longer, so they’re more of them to build the bigger brain. Think of it like this. Leave the programme run 10 minutes longer, you might have 2 progenitor cells. Leave it run 10 minutes longer again, each will subdivide, and you get 4 cells. 10 minutes longer and you get 8 cells, then 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512. As you let the programme run on longer, the eventual structure gets larger at a continuously increasing rate. This is why the human frontal cortex is super big, and the dolphin’s super super big.

- ‘There is no special new part of the bat-brain for navigating using sound‘ – For those wanting to know about bat brains and echolocation, see: Moss CF, Sinha SR. Neurobiology of echolocation in bats. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003 Dec;13(6):751-8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2003.10.016.

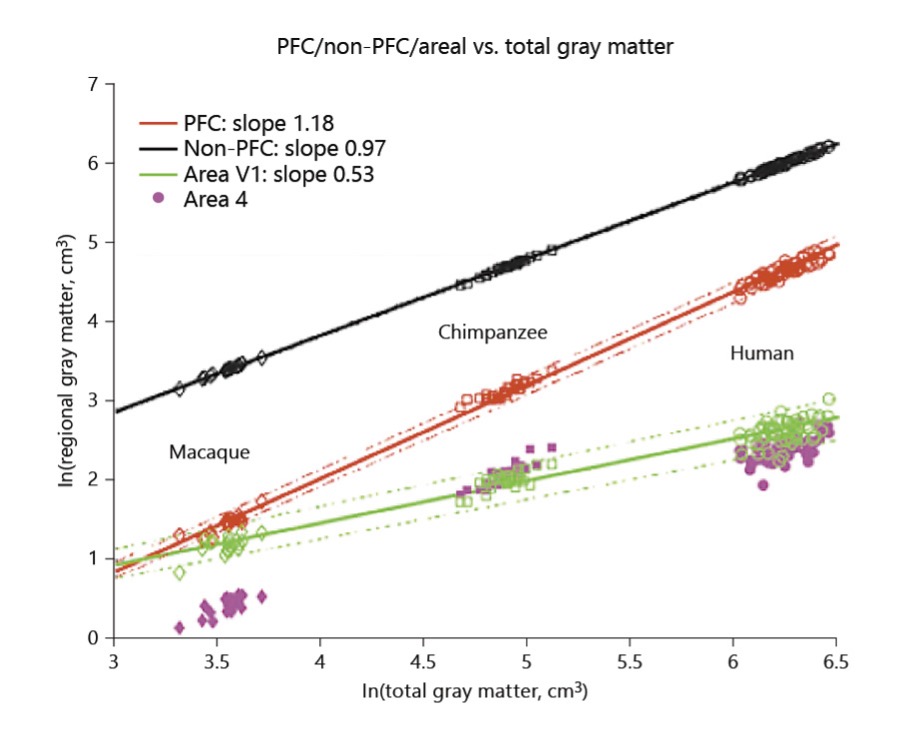

- Here’s the plot looking at variation within each species, for three different primate species. Barbara Finlay says this about the macaque / chimpanzee / human plot: “Human PFC is not disproportionately large, but predictably large. That is, it obeys the scaling formula.” She says (personal communication): “Here’s my favourite plot, a massive amount of data from human, chimp and monkey magnetic resonance imaging. These multiple points on the graph are all individual animals, and look how the individual cortical area volumes each hug their regression lines, all different slopes… I reprinted this in a Karger Symposium paper this year”: Finlay, B. L. (2019). Generic Homo sapiens and Unique Mus musculus: Establishing the Typicality of the Modeled and the Model Species. Brain Behavior and Evolution, 93, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500111. Figure from: Donahue CJ, Glasser MF, Preuss TM, Rilling JK, Van Essen DC. Quantitative assessment of prefrontal cortex in humans relative to nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018 May;115(22):E5183–92. The key point, folks, variation within each species looks like it’s the same as variation between species!

- ‘The variations we see from the smallest adult human brain to the largest correspond to letting this neuron-producing programme run for about 8 days shorter or longer‘ – 8 extra days of brain (isocortex) development to capture within-human variation, taken from Charvet et al. (2013, p.9, p.10): “Simple extension of neurogenesis duration could be the cause of human brain expansion, applied to all brain regions, but with different allometric consequences depending on the relative duration of each brain part production”. DOI: 10.1159/000345940

- Um, if brain size scales with body size, do taller people have bigger brains? And does that then make them more intelligent (since intelligence correlates about 0.3 with brain size)? Answer, yes, a little bit. See: Eero Vuoksimaa, Matthew S. Panizzon, Carol E. Franz, Christine Fennema-Notestine, Donald J. Hagler, Michael J. Lyons, Anders M. Dale, William S. Kremen. Brain structure mediates the association between height and cognitive ability. Brain Structure and Function, 2018; DOI: 10.1007/s00429-018-1675-4

- Per above, we’ll mention again that when we later come to differences between humans, it turns out there are different knobs on the Brain-Builder-5000 for setting the parameters of the cortex and the limbic system (separate principal components of structural variation in morphometric analyses). This partly explains why intelligence (cortex driven) and personality (limbic system driven) are different kinds of human variation, or indeed, types of structural variation across mammals. Though Charvet et al. say (2013, p.10): “Why the limbic system volume varies relatively independently from other brain regions within and across species is not clear.” So, they haven’t yet found the knobs. And as we’ll see later, some of the variation in limbic functionality is likely to be due to distribution of hormone receptors for neuropeptides like vasopressin and oxytocin, not just the size of structures.

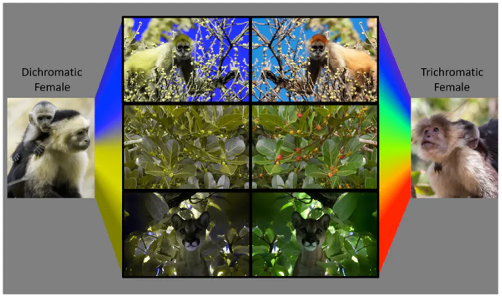

- ‘With modern genetic methods, it’s possible to create a new breed of mice which have additional detectors in their retinas for red light‘ – The mice who see red: Jacobs, G. H., Williams, G. A., Cahill, H. & Nathans, J. 2007 Emergence of novel color vision in mice engineered to express a human cone photopigment. Science 315, 1723–1725. (doi:10.1126/science.1138838)

- For what the blue-yellow vision guys see, see: https://theconversation.com/inside-the-colourful-world-of-animal-vision-30878

- ‘Brains are generalists and will work with whatever sensory information they receive to drive adaptive behaviour.’ – Extending the idea that the central nervous system is a generalist, this means that there’s no destiny in the outcomes of brain development. For example, there’s no detailed function a part of the cortex is intrinsically for. Give a brain a different periphery, sensory input, motor opportunities, or give it a different world to interact with, you get a different functional brain structure (e.g., for recognising written words, for swiping touchscreens). The brain-making machine makes brains with a range of functional outcomes depending on the experiences they receive.

- ‘If the brain-making plan is similar across species, with the knobs set just a bit differently, how do you get species-specific behaviours for all the different mammalian species?‘ – The message here is structure doesn’t predict function. Or to put it another way, it’s hard to look at an animal’s brain structure and tell what its particular behavioural repertoire will be. By the same token, it’s hard to tell what abilities a given human will have based on a scan of their brain structure, beyond some vague guess on their intelligence based on overall brain size. This difficulty in linking brain structure differences to behavioural differences is even found in the field of sex differences in humans. There are sometimes differences in the characteristic behaviour of the sexes, but these are hard to spot in brain structure: van Eijk L, Zhu D, Couvy-Duchesne B, et al. Are Sex Differences in Human Brain Structure Associated With Sex Differences in Behavior? Psychological Science. July 2021. doi:10.1177/0956797621996664.

- ‘The special abilities of each species are likely to come from several sources.’ – The three origins of species-specific behaviours are taken from: Finlay, Barbara L., Hinz, Flora, and Darlington Richard B. 2011. Mapping behavioural evolution onto brain evolution: the strategic roles of conserved organization in individuals and species. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B3662111–2123. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0344

- ‘Evolution generally takes a long time to make any big changes‘ – Finlay (personal communication) says: ‘In general true. However, there are some things that can change pretty quickly, which is interesting – there’s some work just now that Darwin’s finch’s beaks might be like that, also dietary modifications like lactose, or the shift to nocturnal in owl monkeys I worked on, things that have a fundamental environmental instability to them, with peripheral and neural components. In the case of predictable / unpredictable environment (stress) you might get a distinct, epigenetic path to relate life history to an environmental assessment (like Nettle/ Belsky) for small numbers of generations, which is very widespread in vertebrates. But for big reallocations of energy and structure in the brain, you’re completely right!’