In this chapter, we start with the main reason for having a brain in the first place: movement. We then take a tour of the structures, treating the brain as if it had a layers. We start on the surface, standing on the wrinkled ‘cortex’, then dig down to the bizarrely shaped structures that lie within. We pretty much think we’re done when we get to the brain stem. But then we’re startled to find a whole extra mini-brain tucked in at the back of the skull, and that it contains 80% of all the neurons! What’s going on there? Next, we try and be helpful by providing a couple of boxes, one that tells you how to find where you are in the brain (kind of your neural satnav), and then a quick summary of the methods neuroscientists have used to figure out how the brain works.

- ‘The main reason for having a brain is for coordinated movement‘ – The view that the evolutionary origin of the brain is solely about movement is called ‘motor chauvinism’. Here’s a short talk by Daniel Wolpert called “The real reason for brains” where he lays out the evidence: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7s0CpRfyYp8

- ‘Trees don’t move and they have no brains, not even a nervous system‘ -While trees don’t have nervous systems, they have sensory systems of sorts, which can detect damage and trigger plant-wide responses. See: Muday GK, Brown-Harding H. Nervous system-like signaling in plant defense. Science. 2018 Sep 14;361(6407):1068-1069. doi: 10.1126/science.aau9813. PMID: 30213898.

- ‘Leeches have a nervous system that is distributed across their bodies‘ – Leeches have lots of brains: for aficionados, here’s how the leech’s nervous system works: Kristan WB Jr, Calabrese RL, Friesen WO. Neuronal control of leech behavior. Prog Neurobiol. 2005 Aug;76(5):279-327. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.004. Epub 2005 Nov 2. PMID: 16260077.

The tour: Cortex

- ‘The cortex is a sheet of neurons for processing information. It’s just a bit smaller than a sheet of A3 paper‘ – If you’re peckish, here’s another way to think about the size of the cortex: The human cortex is like a pizza, about 50cm across. Deep dish or thin crust, you ask, licking your lips. Well, its average depth is 4 to 5mm, so we’d say thin crust. The cat’s cortex, by comparison, is more the size of a chocolate chip cookie, at 10cm across. Neuroscience can make you hungry. But our advice is that too many carbohydrates can be bad for you.

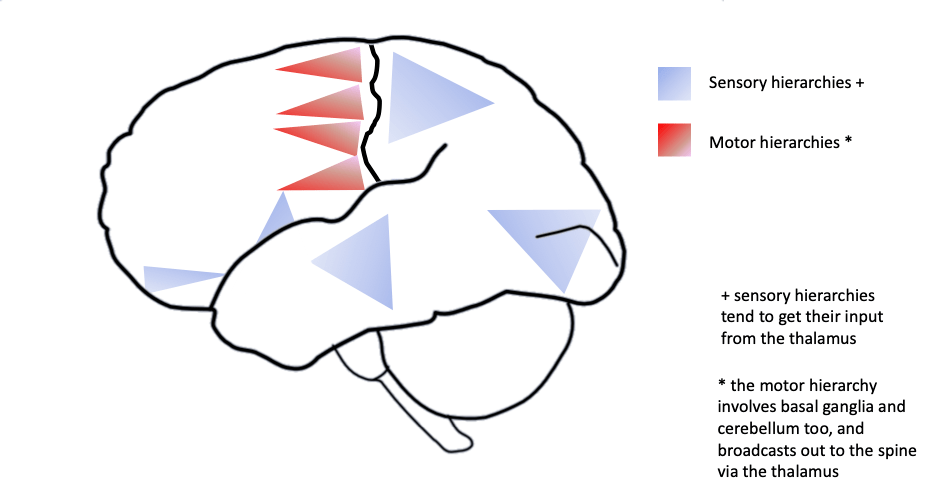

- Here’s a figure showing where you’ll find the sensory hierarchies, each shown by a blue triangle (wide base, narrow top). There’s one per lobe for occipital [vision], temporal [audition], parietal [external body sensation], insula [internal body sensation], and the olfactory bulb [smell]. And then there’s the red motor hierarchies in the frontal lobe, with their base in the motor strip:

- ‘We saw in the section on evolution that humans have more cortex. This means that humans can build their sensory and motor towers higher than other animals‘ – For more on how the greater amount of human cortex allows for towers with more levels, see: Finlay, B. L., & Uchiyama, R. (2014). Developmental mechanisms channeling evolution. Trends in Neurosciences, 38(2), 69-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2014.11.004. They say: ‘[There is a systematic amplification of] hierarchical organization on the rostrocaudal [front-to-back] axis in larger brains. Recent work has shown that variation in ‘cognitive control’ in multiple species correlates best with absolute brain size, and this may be the behavioral outcome of this progressive organizational change’ (p.69). They go on to say: ‘Within the frontal lobe, an increasing hierarchy of decision abstraction with progressively frontal position has been described. The increasing convergence of hierarchically arranged multiple cortical areas on a frontal lobe, itself hierarchical, may be the direct physical correlate of the ability to compare and decide between behavioral alternatives. The automatic increase in the power of hierarchical organization in larger brains for cognitive control, useful to specialist and generalist alike, and driven by conserved developmental mechanisms, may be the key to understanding the advantage of larger brains in nature’ (p.75). In other words, if your species has a bigger brain, the bigger frontal cortex can self-organise across development to provide more sophisticated control over behaviour.

Deeper layers

- ‘If the anterior cingulate is damaged, you can have the same sensation of pain as before, but not be bothered by it anymore‘ – Damage to anterior cingulate leads to preserved pain sensation without linked emotional response: Xiao Xiao, Yu-Qiu Zhang (2018). A new perspective on the anterior cingulate cortex and affective pain. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 90, 2018, Pages 200-211, ISSN 0149-7634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.03.022.

- ‘We said these were ancient memory systems‘ – For the evolutionary history of the amygdala, see: Pabba (2013). Evolutionary development of the amygdaloid complex. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2013.00027. For evolutionary history of the hippocampus, see: Allen TA, Fortin NJ. The evolution of episodic memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jun 18;110 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):10379-86. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301199110.

- ‘These memories can be sequences of moments, like short video snippets‘. Isn’t that cool? For this work, see: Reddy et al. (2021). Human hippocampal neurons track moments in a sequence of events. Journal of Neuroscience 4 August 2021, 41 (31) 6714-6725; DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3157-20.2021. They say: “We show that temporal context modulates the firing activity of human hippocampal neurons during structured temporal experiences … These findings suggest that human hippocampal neurons could play an essential role in temporally organizing distinct moments of an experience in episodic memory.”

- ‘The hippocampus brings together information from all the senses to create snapshot memories of places and events‘. It may also store information about the internal system state in the prefrontal cortex, so that you can answer indignant questions like, what were you thinking?

- ‘Emotions themselves are sets of highly variable instances‘ – emotions are highly variable instances determined by context, see: Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions Are Made (2017, Macmillan). See here for a summary of these ideas. The different types of fear example come from a magazine interview with Feldman promoting her book (Psychologist magazine).

- Cingulate cortex and parahippocampal gyrus are brokers from cortex to the limbic system structures. Technically, these broker areas are ‘mesocortex’ rather the ‘neocortex’. Mesocortex is the transitional areas of the cerebral cortex, formed at borders between true isocortex, evolutionarily newer (hence neo=new) with its common six-layered structure across the sheet (hence iso=same), and the evolutionarily older, 3- or 4-layered allocortex that comprises structures like the hippocampus and olfactory cortex.

- ‘It’s making these selections every few hundred milliseconds‘ – Basal ganglia make action selections every few hundred milliseconds, see: Lindroos R, Dorst MC, Du K, Filipovic ́ M, Keller D, Ketzef M, Kozlov AK, Kumar A, Lindahl M, Nair AG, Pérez-Fernández J, Grillner S, Silberberg G and Hellgren Kotaleski J (2018) Basal Ganglia Neuromodulation Over Multiple Temporal and Structural Scales—Simulations of Direct Pathway MSNs Investigate the Fast Onset of Dopaminergic Effects and Predict the Role of Kv4.2. Front. Neural Circuits 12:3. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2018.00003: They say: “Activation of DAergic terminals within striatum can trigger movement within a few hundred milliseconds”

- ‘The first glimmers of consciousness begin only when the thalamus grows connections up to the cortex‘ – For the proposal that thalamus connecting to the cortex marks the developmental onset of consciousness, here considered in the context of pain experience, see: Lee SJ, Ralston HJP, Drey EA, Partridge JC, Rosen MA. Fetal Pain: A Systematic Multidisciplinary Review of the Evidence. JAMA. 2005;294(8):947–954. doi:10.1001/jama.294.8.947. E.g., “the capacity for conscious perception of pain can arise only after thalamocortical pathways begin to function, which may occur in the third trimester around 29 to 30 weeks’ gestational age” (p.952)

- ‘Eighty percent of the brain’s neurons sit in the cerebellum‘ – The cerebellum contains 80% of the neurons in the human brain, and the number of neurons in the cerebellum scales with the number of neurons in the cortex across species: Herculano-Houzel S (2010). Coordinated scaling of cortical and cerebellar numbers of neurons. Front. Neuroanat. 4:12. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2010.00012. They say: “Strikingly, in contrast with the volumetric preponderance of the cerebral cortex in most mammals, the vast majority of brain neurons are located in the cerebellum across a range of mammals. For instance, the cerebellum holds 60% of all brain neurons in the mouse, small shrews, and marmoset; 70% in the rat, guinea pig and macaque; and 80% in the agouti, galago, and human” (p.1)

- ‘If you were to take an adult human cerebellum and unfold it‘ – For the unfolded adult human cerebellum, see: Martin I. Sereno, Jörn Diedrichsen, Mohamed Tachrount, Guilherme Testa-Silva, Helen d’Arceuil, Chris De Zeeuw (2020). The human cerebellum has almost 80% of the surface area of the neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Aug 2020, 117 (32) 19538-19543; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2002896117. They say: “The unfolded and flattened surface comprised a narrow strip 10 cm wide but almost 1 m long” (p.19538)

- ‘One good example of the models that the cerebellum builds of how to move the body is the phenomenon of sea legs‘ – For more on the idea that sea legs or ‘land sickness’, and the longer lasting version called Mal de Debarquement syndrome, arise as a consequence of forming of an inappropriate internal predictive model in the cerebellum, see: Hain TC, Helminski JO. Mal de Debarquement. in “Vestibular Rehabilitation”, 2nd edn (Ed. S. Herdman), 2007. And see https://dizziness-and-balance.com/disorders/central/MdDS.html for recent discussion, and here for an overview of Mal de Debarquement syndrome.

- The cerebellum seems important given it holds preponderance of the brain’s neurons, but oddly, damage it in an adult and all you see is clumsy motor movements and problems with motor learning. Damage the basal ganglia by contrast, and you lose the ability to initiate voluntary action. Hum.

The simple life

- How the brain works in a simple vertebrate: You’ll still need a cerebellum by the way – this structure is found across vertebrates. Don’t underestimate the complexity of delivering smooth motor behaviour, whether you are a concert pianist or a frog munching on a fly.

- ‘Let’s start with a simple vertebrate, before the limbic system has scaled up, when the cortex is but a wafer‘ – Simple vertebrate vs vertebrates with scaled-up limbic systems. We’re making out that frogs are dummies… Well, even though the frog is a largely stimulus-driven amphibious creature, its brain still has a yet-to-be-scaled-up version of the limbic system: Laberge F, Mühlenbrock-Lenter S, Grunwald W, Roth G. Evolution of the amygdala: new insights from studies in amphibians. Brain Behav Evol. 2006;67(4):177-87. doi: 10.1159/000091119. Epub 2006 Jan 23. PMID: 16432299: They say: “the histology of amphibian brains gives an impression of relative simplicity when compared with that of reptiles or mammals … [however] the connectivity of the amphibian telencephalon portends a capacity for multi-modal association in a limbic system largely similar to that of amniote vertebrates.” So they are dummies laced with potential.

- ‘In ancestral brain-making plans, this management role may once have fallen to the cingulate cortex‘ – Cingulate cortex as pre-mammalian integrating structure over limbic and basal ganglia, from Amthor, F. (2016). Neuroscience for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: New Jersey, USA.

- ‘Because scaling up the cortex is an evolutionarily new thing, the cortex is sometimes called the neocortex‘ – You’ll find a similar non-scaled up version of the cortex in birds, where it’s called the pallium. Pallium is Latin for cloak, while cortex is Latin for bark. The scaled-up human cortex is scrunched up to fit in the skull, giving it a more wrinkled appearance, hence the surface of bark, while the pallium is a smoother enclosing structure, hence cloak. Recent evidence suggests that the neurons in the mammalian cortex are evolutionarily different from the neurons in the pallium, implying that the cortex and pallium may have similar functional roles but have different evolutionary origins: Woych J, Ortega Gurrola A, Deryckere A, Jaeger ECB, Gumnit E, Merello G, Gu J, Joven Araus A, Leigh ND, Yun M, Simon A, Tosches MA. Cell-type profiling in salamanders identifies innovations in vertebrate forebrain evolution. Science. 2022 Sep 2;377(6610):eabp9186. doi: 10.1126/science.abp9186.

- ‘The most ancient parts of the brain aren’t left alone when other parts enlarge but end up co-evolving with them, so that, at least in terms of types of neurons, the brain is a mosaic of old and new across all its parts’ – Hain D, Gallego-Flores T, Klinkmann M, Macias A, Ciirdaeva E, Arends A, Thum C, Tushev G, Kretchmer F, Tosches MA**, Laurent G** (2022). Molecular diversity and evolution of neuron types in the amniote brain. Science 377 (6610). For discussion, see: https://www.quantamagazine.org/gene-expression-in-neurons-solves-a-brain-evolution-puzzle-20230214/

- ‘But that would be a mistake: an old-fashioned, early 20th Century Freudian view of the mind‘ – The example for rejecting an incorrect Freudian view of impulsivity is adapted from: Cesario, J., Johnson, D. J., Eisthen, H. L. (2020). Your brain is not an onion with a tiny reptile inside. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(3), 255-60: They say: “All animals make decisions between actions that involve trade-offs in opportunity costs [guarantee returns now versus less predictable rewards further in the future] … impulsivity can be understood as an adaptive response to the contingencies present in an unstable environment rather than a moral failure in which animalistic derives overwhelm human rationality” (p.258).

Postscript

- To situate where we are in understanding the function of different structures of the brain, it may be worth mentioning that there are still structures where we don’t know what they do. For example, the claustrum (Latin meaning ‘to shut’) is a thin sheet of neurons and glial cells located between the insula lobe and the putamen (part of the basal ganglia). It is one of the most densely connected structures in the brain, connecting to cortical areas (e.g., the prefrontal cortex, but also multiple sensory areas) and subcortical structures such as the thalamus, often with bi-direction connections between these regions. It’s found across all mammals. What is it for? Perhaps, given its connectivity, it is involved in the integration of cortical inputs, such as vision, sound, and touch, into a single experience. Some have speculated that it plays a role in generating the unified experience of consciousness. Koch et al. (2016) discuss a case study of a patient ‘implanted with electrodes for remedial surgery to treat epileptic seizures’ and how ‘electrical stimulation of the white matter tract underneath the claustrum caused the patient to stare blankly ahead, seemingly unconscious, until the stimulation had stopped, without subsequent recall and without causing any seizure activity’; but then another who had had the claustrum and neighbouring limbic structures destroyed bilaterally through herpes simplex encephalitis, who nevertheless appeared to be conscious. Confusing, huh? Perhaps the claustrum plays a computational role in binding and coordination, a kind of conductor for the neural orchestra, keeping all the plays (perceptual, cognitive, and motor) in synch? We don’t know. And that’s where we’re at. (p.310, Koch C, Massimini M, Boly M, Tononi G. Neural correlates of consciousness: progress and problems. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016 May;17(5):307-21. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.22. PMID: 27094080).