In this chapter, we get stuck into how a neuron works, and how neurons talk to each other. It turns out that neurons have both important electrical properties and important chemical properties. And that they are not even properly connected to each other. Which brings us on to neurotransmitters. Neurons are not properly connected but they can transmit to each other… And when we’ve got this far, it all begins to sound so complicated that we lose confidence that something like this could have ever evolved starting from, presumably, some kind of amoeba living in a primeval puddle. So then we explain how neurons probably evolved. And then we introduce you to a happy neuron.

- ‘Neurons don’t just pass on the stimulation they receive to the next neurons like a baton – they only pass it on if their threshold is exceeded, and it is in this way that they make a decision’ – Technically, we say the mathematical function that transforms the input into the output is non-linear. Output doesn’t steadily go up with increases in input, which would be linear, just amplifying a signal rather than processing it; instead, output goes up suddenly when a certain level of stimulation is exceeded, making it non-linear. There is a sharp increase when the neuron’s threshold is exceeded. This is what we mean by saying the neuron makes a mini-decision. In this sense, then the brain is a non-linear computational device, part of the broader theory of neural computation.

Electrical properties of neurons

- Figure 4.1, one of Cajal’s original drawings of neurons, is taken from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PurkinjeCell.jpg

- ‘The whole process, from initial opening of channels to the return to -70mv, takes about 3-4 milliseconds’ – Voltage gated channels flip open in 3-4 msecs. We compare that to the blink of an eye, which is about 100 msecs.

- How many inputs to each neuron? On average, a neuron receives inputs from 10,000 other neurons. This is one of the reasons why a neuron has dendrites: there just isn’t enough room for 10,000 axons to make contact with the cell body of a neuron, it’s too small. So the cell body grows a tree with plenty of branches for all those axons to make contact with.

- ‘When neurons are working hard – lots of action potentials, lots of resetting – calcium ions build up outside the neuron. This creates a signal that is passed on to nearby vessels (by astrocytes – see later!). In turn the vessels dilate and bring in more oxygenated blood‘ – The link between sustained neural activity, astrocyte activity, calcium signalling, and the regulation of vascular tone is modestly complicated. For researchers, this is important, because the link between neural activity and the Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent signal used in functional MRI depends upon these relationships. If you want a taste of this complexity, see this paper: Wang X, Takano T, Nedergaard M. Astrocytic calcium signaling: mechanism and implications for functional brain imaging. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;489:93-109. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-543-5_5. PMID: 18839089; PMCID: PMC3638986; or this paper: Hillman EM. Coupling mechanism and significance of the BOLD signal: a status report. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:161-81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014111. PMID: 25032494; PMCID: PMC4147398.

Chemical properties of neurons

- How big is a synaptic gap or cleft? For those fond of splitting hairs, the size of the synaptic gap is about one three thousandth of the width of a human hair.

- ‘The synapse is so small that the molecules of neurotransmitter can diffuse over to the postsynaptic membrane in a half a millisecond’ – half a millisecond estimate comes from here: Welsh, T. (2015). It feels instantaneous, but how long does it really take to think a thought? Conversation.

- ‘Well, direct wired connections are found in some places in the brain‘ – these are called electric synapses. See here: Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors. Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001. Electrical Synapses. For recent work on where these are found in the brain and what they do, see this paper: Vaughn MJ and Haas JS (2022). On the Diverse Functions of Electrical Synapses. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 16:910015. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.910015

- ‘In 1973, Bliss and Lomo managed to directly test the idea.’ – Here’s the classic paper testing Hebb’s idea that the more frequently a presynaptic neuron stimulates a postsynaptic neuron, the stronger that synapse will become and the more likely it will be to fire in the future, now called long-term potentiation: Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973 Jul;232(2):331-56. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. PMID: 4727084; PMCID: PMC1350458.

- ‘There are two hundred and thirty-seven types of neuron‘ – 😃 we made up this number and picked the value 237 for two reasons: (a) to show how spurious precision is in answering this question; and (b) based on some attempts to answer the question which suggest the number of types, as used by neuroscientists in practice, is in the hundreds: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/brainwaves/know-your-neurons-classifying-the-many-types-of-cells-in-the-neuron-forest/

Wow, I mean, literally, where did all that come from?

- ‘How can this kind of spectacular specialist cellular function have come about through evolution?‘ – For the evolution of neurons, the arguments are based on: Kristan, W. B. (2016). Early evolution of neurons. Current Biology 26, R937–R980, October 24, 2016 R951. Kristan also says: ‘Did neurons evolve more than once? Almost certainly. [While in most species, neurons are derived from the same epidermal line as skin cells] some cnidarian [aquatic invertebrate] neurons derive from endodermal cells … It may turn out that, once a cell type has acquired the basic molecular constituents to make action potentials and synapses, making these cells into neurons was relatively easy’ (p.R954)

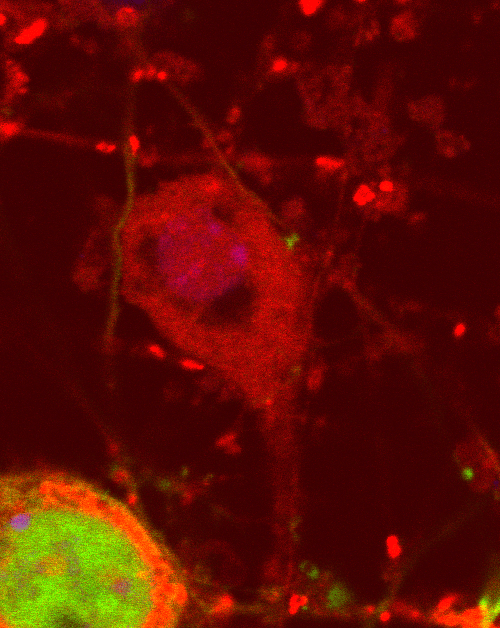

- Here’s the happy neuron in full colour. Dr. Ane Goikolea-Vives generated this image in Dr. Helen Stolp‘s lab while investigating mitochondria in mouse neurons using staining techniques. Here’s some more information on this image to give a sense of what in vitro investigation of neurons involves. Ana comments: ‘I found this neuron by pure chance while imaging a target cell. This is a mouse embryonic day 14 cortical neuron, from the lateral / outermost side of the brain, which spent 7 days in culture. I’m not sure what the eyes and mouth of the happy face are, maybe vacuoles [spaces within the cytoplasm of a cell, enclosed by a membrane and typically containing fluid] or an artifact such as non-homogenous staining. This staining is not perfect as it stains mitochondria randomly. My target cell is the one that stands out with properly stained mitochondria (red), and the happy face is in the very background with no mitochondria at all. So the happy neuron didn’t pick up the staining. In the happy neuron image I sent you, I cropped the original image and adjusted the brightness and contrast to see the big smile. The mouth and eyes could also be due to the exact z-plane in the microscope and the happy neuron’s shape. I was aiming to image the target cell’s mitochondria network and since I took this image with the SP8 Leica confocal microscope, I only have an image of that exact z location, so the image lacks the rest of the things that could be over or under that exact scan of the cell. We could assume the lines in the image are dendrites, but we don’t know for sure if they are dendrites or axons since I didn’t stain specifically for those. There are neurites [small outgrowths from neuronal bodies] from other neurons that don’t appear in this field of view so it’s also possible the neurites we see in this image are a mix from different neurons. Mitochondria sit among actin filaments and microtubules. The green is enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP). I infected these cells with an eGFP-expressing adenovirus, so that a percentage of cells only were green. This eases visualisation and selection of cells for imaging.’

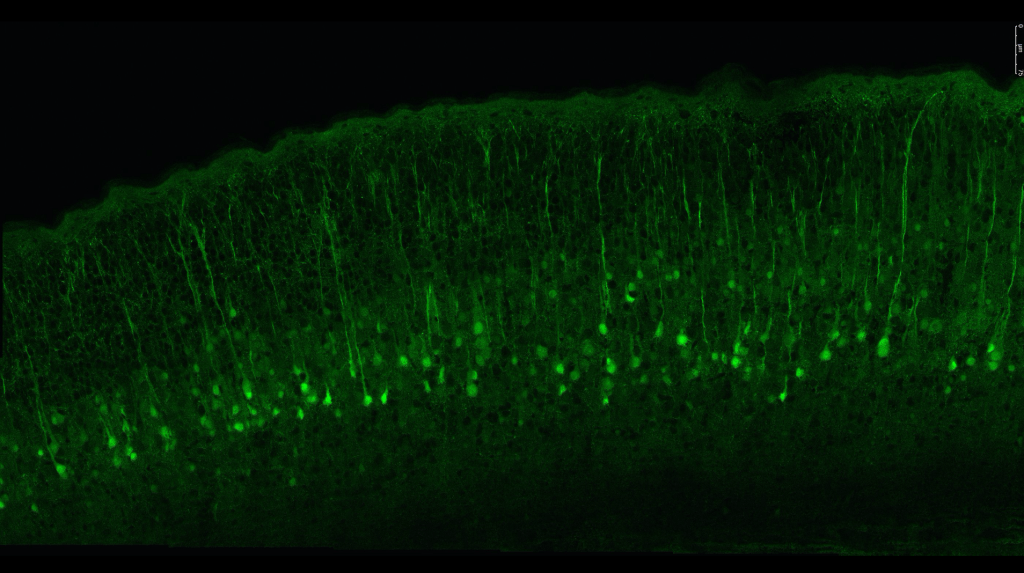

- Here’s another of Ana’s images captured in Helen Stolp’s lab, showing how neurons are organised in the cortex of the mouse brain.