This chapter views the brain as if it were a computer, and figures out what kind of computer it would have to be – since it has to do its computations with neurons and it must store all its knowledge in the strength of the connections between them. It turns out that it will have to work very differently from a digital computer, which moves information very quickly between general purpose processing devices (the CPU, RAM, hard disk). Instead, the brain uses devices like hierarchies, maps, hubs, and networks. We venture into the executive suite in the prefrontal cortex, a region renowned for decision making and cognitive control capacities, to see what’s going on in there. We consider how the human brain processes its favourite content: other people. And how the brain is always trying to predict what is about to happen next so it can be ready – but this makes it fall for magic trips. And we finish by considering how the brain decides whether or not it’s happy, deep down.

The cortical sheet

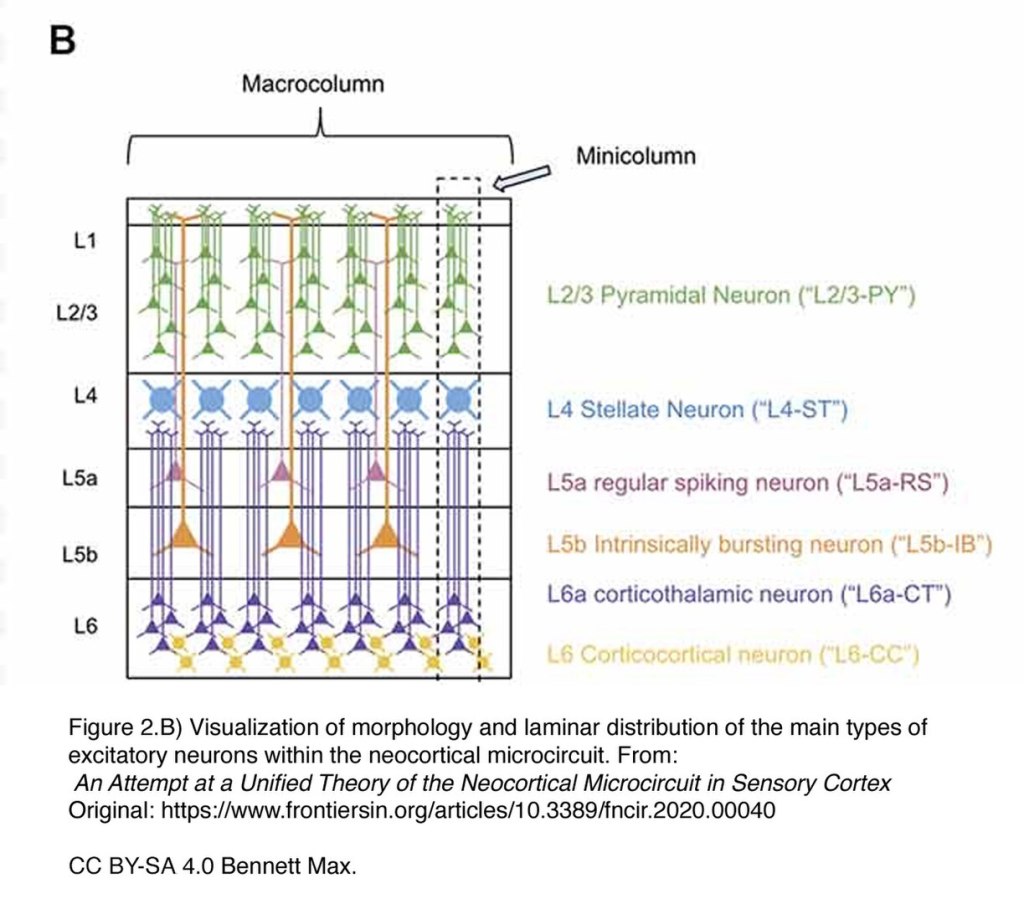

- ‘Broadly speaking, the cortical sheet looks the same all over … On the small scale, the neurons are organised into mini-columns that span the six layers, each of around 100 neurons; it’s a tiny consistent circuit, which is then repeated millions of times across the cortical sheet‘ – Here’s a nice diagram showing this basic unit of computation, from: Bennett, Max (July 2020). An Attempt at a Unified Theory of the Neocortical Microcircuit in Sensory Cortex. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 14: 40. doi:10.3389/fncir.2020.00040 (Figure 2B):

The digital computer – a way the brain could have worked but doesn’t

- ‘In our recent history, chess has been held up as the game not just of kings but of geniuses‘ – Chess as a metaphor for intelligence: ‘the game not just of kings…’ quote adapted from https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/a-brutal-intelligence-ai-chess-and-the-human-mind/

- Digital computation and mapping the brain to the mind #1: The metaphor of a digital computer also cautions us against expecting a simple mapping from psychological concepts to brain processing. As we’ve seen, one thing in the mind is many things in the brain. But consider, would it make any sense to ask which part of a Nintendo Switch runs Super Mario Kart or Grand Theft Auto? Which part of the Nintendo Switch produces the cars in these games? (other consoles are available). Would it make any sense to ask which part of the MacBook runs the Inbox on your email? (other computer brands are available). Obvious units of functionality do not readily align with units of mechanism even in a digital computer.

- Digital computation and mapping the brain to the mind #2: As well as serving as a metaphor of the mind, the digital computer (or at least, the microprocessor it contains) has allowed neuroscientists to test the adequacy of their methods to reveal the workings of an information processing device, such as functional magnetic resonance, lesion studies, electrophysiology, or single cell recording. In this case, the functional architecture is completely understood because it was designed by humans. Researchers asked: if you were to use neuroscience methods on a computer chip, could you figure out how it works? Here’s what these guys did: in an analogy to functional magnetic resonance imaging, scientists tested which parts of the chip got hotter when the system played three different 1980s video games, Donkey Kong, Space Invaders, and Pitfall; in an analogy to lesion studies, they tested which games or parts of games failed when different bits of the chip were damaged; and in an analogy to electroencephalography and single cell recording, they examined the correlations between electrical signalling in individual transistors on the chip and game performance. They found that these methods only recovered a rudimentary sketch of the microprocessor’s function, compared to the known correct answer (sequential control of logic gates). This example demonstrates exactly how hard the enterprise of neuroscience is, at least with the methods we currently have. See: Jonas E, Kording KP (2017) Could a Neuroscientist Understand a Microprocessor? PLoS Comput Biol 13(1): e1005268. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005268.

How does the brain work, then?

- ‘Because knowledge is built into the structure of the brain – in the strength of the connections between neurons – it is very hard to move around‘ – For more on how computation in neural networks requires a different sort of overall computer architecture, see: Thomas, M. S. C., & McClelland, J. L. (2023). Connectionist Models of Cognition. In: R. Sun (Ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of Computational Cognitive Sciences (pp. 29-79). Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108755610. Uncorrected proof.

- ‘A hippocampus can store perhaps 50,000 memories, and you have a hippocampus on each side of your brain‘ – Here’s a paper showing how this estimate of the hippocampus’s memory capacity was derived: Kesner, R. P., & Rolls, E. T. (2015). A computational theory of hippocampal function, and tests of the theory: New developments. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 48, January 2015, Pages 92-147. The estimate is based on how many neurons there are in the hippocampus, how many connections there are between them, and computer science theory of the information that can be stored within neural networks. WARNING: may contain heavy-duty neuroscience!

Hierarchies, maps, hubs, and networks

- ‘These topographic maps are also retained as you ascend the hierarchies. Nearby neurons in the higher map continue to be activated by nearby neurons in the map below‘ – Topographic maps are found in higher cortical areas: Sood MR, Sereno MI. Areas activated during naturalistic reading comprehension overlap topological visual, auditory, and somatotomotor maps. Human Brain Mapping. PMID 27061771 DOI: 10.1002/hbm.23208

- We show the visual hierarchy as an example. Here’s a paper outlining what the smell hierarchy might look like, from odours to scents (at least in our mammalian cousin, the mouse): Yang W, Sun QQ. Hierarchical organization of long-range circuits in the olfactory cortices. Physiol Rep. 2015 Sep;3(9):e12550. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12550. PMID: 26416972; PMCID: PMC4600391. And here’s some work on the human hierarchical smell system: Zhou G, Lane G, Cooper SL, Kahnt T, Zelano C. Characterizing functional pathways of the human olfactory system. Elife. 2019 Jul 24;8:e47177. doi: 10.7554/eLife.47177. PMID: 31339489; PMCID: PMC6656430.

- ‘How does the brain know that the red colour goes with the apple shape and the orange colour with the orange shape? This is called the binding problem.’ – Here’s a recent paper speculating on how the brain might solve the binding problem: Roelfsema PR. Solving the binding problem: Assemblies form when neurons enhance their firing rate-they don’t need to oscillate or synchronize. Neuron. 2023 Apr 5;111(7):1003-1019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.03.016. PMID: 37023707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2023.03.016. This author, Pieter Roelfsema, argues for the view that “enhanced neuronal firing rates bind features into coherent object representations, whereas oscillations and synchrony are unrelated to binding.”

- How do you store integrated knowledge across different content-specialised systems… The brain’s solution to this problem is to have hubs‘ – Here’s a paper outlining one method neuroscientists use for discovering hubs, outlining the main hubs identified with the method, and how they change across development: Oldam, S., & Fornito, A. (2019). The development of brain network hubs. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, Volume 36, April 2019, 100607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.12.005

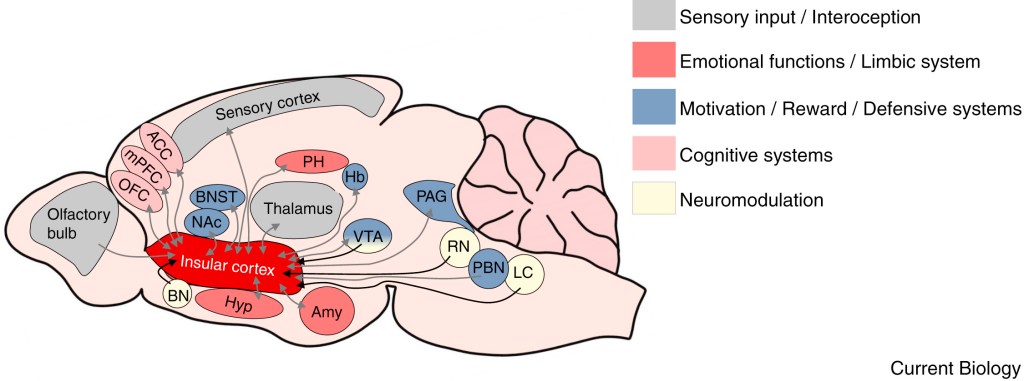

- ‘Hubs are regions where information is brought together and bound into single representations. A hub is therefore a focus of connectivity in the brain’s overall network … The insular lobe has a hub that integrates sensory information from the cortex with emotion information from the limbic system to give valence (emotional value) to concepts‘ – Here’s a great diagram of the insula in the mouse, showing all the connectivity from different brain areas leading into this hub. The image is from: Gogolla N. The insular cortex. Curr Biol. 2017 Jun 19;27(12):R580-R586. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.010 (Figure 2).

- Interestingly, the brain’s hubs are vulnerable components. Two major hubs, the anterior temporal cortex (amodal representations of semantic categories) and the hippocampus (episodic memory and spatial maps) are two of the systems that first show decay in Alzheimer’s disease, producing a loss of word meaning knowledge in the former, and loss of autobiographical memory and navigation skills in the latter: Meichen Yu, Marjolein M. A. Engels, Arjan Hillebrand, Elisabeth C. W. van Straaten, Alida A. Gouw, Charlotte Teunissen, Wiesje M. van der Flier, Philip Scheltens, Cornelis J. Stam, Selective impairment of hippocampus and posterior hub areas in Alzheimer’s disease: an MEG-based multiplex network study, Brain, Volume 140, Issue 5, May 2017, Pages 1466–1485, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx050. And more recently from same authors: Yu, M., Sporns, O. & Saykin, A.J. The human connectome in Alzheimer disease — relationship to biomarkers and genetics. Nat Rev Neurol 17, 545–563 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00529-1.

- Speculatively, this vulnerability may be because hub zones are frequently activated and wear out first when the whole system is declining: de Haan W, Mott K, van Straaten ECW, Scheltens P, Stam CJ (2012) Activity Dependent Degeneration Explains Hub Vulnerability in Alzheimer’s Disease. PLOS Computational Biology 8(8): e1002582. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002582

Horses for courses

- In other mammals, such as rats, the hippocampus looks like it acts as a spatial map of the immediate environment to aid navigation. Cells in the rat hippocampus reliably fire when the rat revisits the same location in their environment. These neurons are called ‘place cells’. When rats learn a route through their environment, the same order of location cells is reactivated during sleep, as if the rat were replaying the memory snippet of its path in its dreams (Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL. Replay of neuronal firing sequences in rat hippocampus during sleep following spatial experience. Science. 1996 Mar 29;271(5257):1870-3. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1870. PMID: 8596957). In humans, the hippocampus likely contributes to this spatial navigation role as well, because damage to the structure in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with loss of navigation abilities (getting lost and disorientated). But human hippocampus is often associated with the broader notion of episodic or autobiographical memory. Nevertheless, it appears to function in a similar way to our rodent cousins. For example, the storage of ’sequence of events’ information in the hippocampus was recently demonstrated in the human brain as well (Reddy et al. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3157-20.2021).

- One could reconcile the autobiographical memory and spatial map functions of the hippocampus either by viewing human autobiographical memories as frequently rooted in the place they occur, so linked to navigation; or the rat’s main interest in life being about the places it has explored, sewers and rubbish bins and the like, so that its autobiographic memory is mainly filled up with places it has visited.

- ‘We do know that once memories are stored in cortex, surgeons can reactivate very specific memories with pinpoint stimulation of cortex during open brain surgery, while the patient is awake‘ – To trigger specific episodic memories by focal stimulation of exposed cortex, the relevant regions to trigger vivid episodic memories are generally in the temporal lobe, variously lateral, ventral, occipito-temporal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus. The example of the coat-on-backwards memory is taken from page 5 of: Jonathan Curot, Franck-Emmanuel Roux, Jean-Christophe Sol, Luc Valton, Jérémie Pariente, et al. Awake Craniotomy and Memory Induction Through Electrical Stimulation: Why Are Penfield’s Findings Not Replicated in the Modern Era?. Neurosurgery, 2020, 87 (2), pp.E130-E137. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyz553, pdf here. The example of high-school memories is taken from: Jacobs J, Lega B, Anderson C. Explaining how brain stimulation can evoke memories. J Cogn Neurosci. 2012 Mar;24(3):553-63. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00170. Epub 2011 Nov 18. PMID: 22098266, on page 555.

- There are still disputes in exactly how the hippocampus works. For example, the neuroscience here juggles between two theories, one that the hippocampus stores immediate memories of events and then these are later transferred to cortex; the other that the cortex forms long-term memories straight away but can only build them very slowly, while the hippocampus forms them quickly, after which the memories weaken. Here’s the sort of experiment that neuroscientists are designing to decide which idea is right, this one run with mice with glowing brains: Kitmura, T., Ogawa, S., Roy, S., et al. (2017). Engrams and circuits crucial for systems consolidation of a memory. Science, 7 Apr 2017, Vol 356, Issue 6333, pp. 73-78. DOI: 10.1126/science.aam6808

Inside the executive suite

- ‘There are neuroscientists who prefer this view of the frontal cortex, as just a gradient of greater abstraction/invariances, of greater complexity as one travels forward in the brain from motor cortex‘ – For neuroscientists who prefer the view of prefrontal cortex as a back-to-front gradient of increasing abstraction of control, see, e.g., Badre D. Cognitive control, hierarchy, and the rostro-caudal organization of the frontal lobes. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008 May;12(5):193-200. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.004. Epub 2008 Apr 9. PMID: 18403252.

- ‘This extensive connectivity supports the prefrontal cortex’s role in cognitive control, and in integrating between state of arousal, emotions, and plans‘ – By contrast, as an example of neuroscientists who prefer to think of PFC in terms of modulation rather than abstraction, Miller and Cohen (2001) define the PFC’s function in this way: “we propose that cognitive control stems from the active maintenance of patterns of activity in the prefrontal cortex that represent goals and the means to achieve them. They provide bias signals to other brain structures whose net effect is to guide the flow of activity along neural pathways that establish the proper mappings between inputs, internal states, and outputs needed to perform a given task.” (p.167). See: Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167

- ‘The prefrontal cortex has been estimated to contain 8% of the neurons in the cortex‘ – Stat that prefrontal cortex contains 8% of cortical neurons: Mariana Gabi, Kleber Neves, Carolinne Masseron, Pedro F. M. Ribeiro, Lissa Ventura-Antunes, Laila Torres, Bruno Mota, Jon H. Kaas, Suzana Herculano-Houzel. (2016). No relative expansion of the number of prefrontal neurons in primate and human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Aug 2016, 113 (34) 9617-9622; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1610178113.

- ‘Benchmarking the computational power you get out of a bunch of neurons. It only takes one million neurons to run a honeybee … A single prefrontal cortex has the computational power of a hive of 1,300 bees‘ – When we were trying to benchmark the computational power of the prefrontal cortex, we were initially thinking in terms of megabytes and gigabytes, or numbers of parameters, but this proved too unconstrained. (We got to something like figuring that each cubic millimetre of the brain had maybe a billion synapses, perhaps sorting a gigabyte of information, 1 byte per synapse, enough to store 500 copies of the novel War and Peace, or a 90 minute movie…). But really, in formal computational terms, we don’t yet know the processing power of even a single neuron given its complex dendrites, receptors, electrical properties, axonal arbors, and neurotransmitter repertoires…

- So instead, we decided to benchmark computational power based on the complexity of behaviour a given number of neurons could generate, albeit in a quite different species. Here’s our reference for the claim that the honeybee brain contains around a million neurons: Menzel R, Giurfa M. Cognitive architecture of a mini-brain: the honeybee. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001 Feb 1;5(2):62-71. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01601-6. PMID: 11166636. And here’s what the honeybee brain can do: “Bees, for example, can count, grasp concepts of sameness and difference, learn complex tasks by observing others, and know their own individual body dimensions, a capacity associated with consciousness in humans. They also appear to experience both pleasure and pain. In other words, it now looks like at least some species of insects—and maybe all of them—are sentient” (Chittka, 2023). That’s what makes it seem so odd that with thirteen hundred times this processing power, our prefrontal cortex can’t keep a 9-digit telephone number in mind…

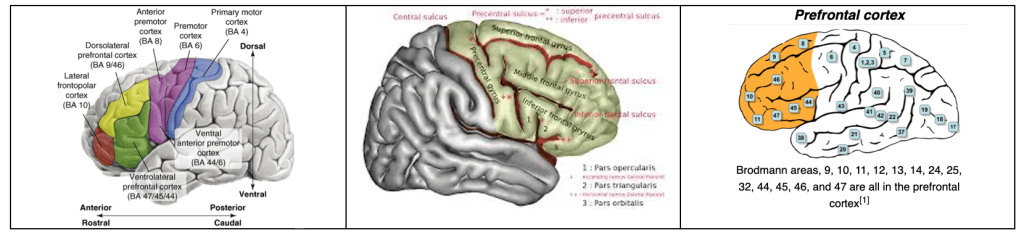

- ‘Neuroscientists have been particularly confusing in how they refer to regions in the prefrontal cortex, mixing up spatial location and gyri and Brodmann areas‘ – Re terminology and prefrontal cortex: The frontal cortex is a domain where neuroscientists have been particularly confusing in their use of terminology. Some refer to regions of the frontal cortex as to whether they are on a gradient of back to front (caudal to rostral, posterior to anterior); some as to whether regions are on top (dorsal), underneath (ventral), in the middle (medial) or to the side (lateral); some refer to a list of Brodmann areas, like 44 or 10; some use names of areas (Broca’s area, frontal operculum; some even include the cingulate cortex); some refer to locations by the characteristic folds in the cortical sheet, the gyri and sulci (in the frontal cortex, there are three main gyri and the sulci in between them: superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri; add a fourth, the precentral gyrus at the back which houses the primary motor cortex, to make up the rest of the frontal lobe). All this terminology has led to confusion between neuroanatomists, neuroscientists, and cognitive neuropsychologists about what happens where. We use a simpler scheme to identify areas of the prefrontal cortex with three questions: Are you on top or underneath? Are you in the middle or at the sides? Are you lying right at the front just above the eye sockets (orbits)?

- Here’s some example graphics grabbed from the internet that use the different labelling approaches, brain brain area (left), by sulcus and gyrus (centre), and by Brodmann area (right):

- ‘Other machinery here is involved in re-orienting spatial attention to perceptual events occurring outside the current focus of attention‘ – For example of ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the reorienting of spatial attention: Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron. 2008 May 8;58(3):306-24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.017. PMID: 18466742; PMCID: PMC2441869.

- You know, actually, we’ve mentioned attention in several places in the book so far, referring to different bits of the brain that may have attention-linked roles. For clarity, let’s pull those together here, in a nice bubble diagram. When the brain pays attention, here’s what it does: task set maintenance and switching, appetitive influencing of perceptual features, detecting and filtering of emotionally salient stimuli, top-down biasing of sensory features in perception, orienting to a region in space for action, inhibiting distracting information, tracking a small number of moving objects, sensory prediction for space of bodily touch, mental effort, fast automatic switching between sensory modalities, and an alarm system. These are the bits of the brain that do attention:

- ‘If you ask someone to roleplay, to act not like themselves, you’ll see this machinery becoming less active‘ – Evidence of reduced activation in dorsomedial PFC when you’re acting: Brown S, Cockett P, Yuan Y (March 2019). The neuroscience of Romeo and Juliet: an fMRI study of acting. Royal Society Open Science. 6 (3): 181908. doi:10.1098/rsos.181908.

- ‘If you’re going to display acts of courage to overcome your fears (go on, grab the snake), this machinery will be buzzing away, inhibiting emotions and activating plans‘ – For evidence that courage involves ventromedial PFC: Nili U, Goldberg H, Weizman A, Dudai Y (June 2010). Fear thou not: activity of frontal and temporal circuits in moments of real-life courage. Neuron. 66 (6): 949–62. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.009.

- ‘When you make a decision from the gut, when you make a decision about risk, reward, and danger, when you decide to gamble, it’s your orbitofrontal cortex‘ – Regarding the orbitofrontal cortex and gambling, we’re not super good about making decisions about risks and rewards, certainly not in terms of probability. If we were, there wouldn’t be a gambling industry, because in gambling the “house”, not you, always wins in the long run… And we know that… And we still gamble.

- ‘YouTube curators have compiled a video of 35 instances of characters in films having bad feelings about things‘ – Here are those 35 movie scenes where Hollywood characters saying they have ‘a bad feeling about this’: https://youtu.be/ZGLHW1hY-CY

- ‘Why the limited capacity?‘ – Speculations on why PFC may have a limited capacity: Botvinick, M.M. and Cohen, J.D. (2014). The Computational and Neural Basis of Cognitive Control: Charted Territory and New Frontiers. Cogn Sci, 38: 1249-1285. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12126. See p.1268-9.

- ‘The prefrontal cortex is also affected by stress … even while other cognitive functions such as rapid learning are actually improved‘ – Evidence that PFC function is impaired by stress but learning is improved: Arnsten, A. F. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 10(6), 410-422. doi:10.1038/nrn2648.

So, what does a concept look like?

- ‘The brain is full of partial representations, fragments of knowledge, that coalesce, perhaps sometimes uniquely, to provide concepts adapted to circumstances‘ – Partial representations of concepts: Fuller explanations about how the brain develops partial representations of knowledge can be found in: Sirois S, Spratling M, Thomas MSC, Westermann G, Mareschal D, Johnson MH. Précis of neuroconstructivism: How the brain constructs cognition. Behav Brain Sci. 2008 Jun;31(3):321-31; discussion 331-56. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0800407X. PMID: 18578929. pdf.

The brain’s favourite content

- ‘Human cortical size may be more about Christmas dinner than Christmas intrigue‘ – What’s more important for brain size, the size of your social group or what your typical level of nutrition support? Here’s the social brain hypothesis: Dunbar, R. I. M. The social brain hypothesis. Evol. Anthropol. 6, 178–190 (1998). Here’s the diet hypothesis: DeCasien, A., Williams, S. & Higham, J. Primate brain size is predicted by diet but not sociality. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 0112 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0112. And here’s some recent doubts about the correlations underpinning the social brain hypothesis: Lindenfors P, Wartel A, Lind J. ‘Dunbar’s number’ deconstructed. Biol Lett. 2021 May;17(5):20210158. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2021.0158. Epub 2021 May 5. PMID: 33947220; PMCID: PMC8103230.

- ‘Many systems contribute to processing ‘people’ information in the brain‘ – For a consideration of the types of computations that the brain runs to process other people (because we’re in the computation chapter), see: Molapour T, Hagan CC, Silston B, Wu H, Ramstead M, Friston K, Mobbs D. Seven computations of the social brain. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2021 Aug 5;16(8):745-760. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsab024. PMID: 33629102; PMCID: PMC8343565. The seven social computations that these authors list are: (i) social perception; (ii) social inferences, such as mentalizing; (iii) social learning; (iv) social signalling through verbal and nonverbal cues; (v) social drives (e.g., how to increase one’s status); (vi) determining the social identity of agents, including oneself and (vii) minimizing uncertainty within the current social context by integrating sensory signals and inferences. Human brains love people.

- ‘In the immediate future, artificial intelligence will likely only augment rather than entirely replace the human driver‘ – Here’s some discussion on the immediate future of autonomous vehicles: Hancock, P. A., Nourbakhsh, I., & Stewart, J. (2019). On the future of transportation in an era of automated and autonomous vehicles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Apr 2019, 116 (16) 7684-7691; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1805770115

There are two sides to every brain

- ‘You’re deemed prettier if there’s one eye on each side of your face (evenly spaced)‘ – See here for more on facial symmetry and attractiveness.

- ‘You’ve got two duplicate computers to start with. If one gets broken early on, you can use the other instead. This is a principle we apply to human-made devices that we really, really want to work, like the James Webb telescope‘ – completely redundant computer systems in the James Webb telescope: see here for more on JWST.

- ‘Don’t fall for brain myths, unless you happen to be using only 10% of your brain‘ – For more on brain myths about left and right brain thinkers, see: http://www.educationalneuroscience.org.uk/resources/neuromyth-or-neurofact/left-brain-versus-right-brain-thinkers/.

- Hey, the 10% of your brain myth even has its own Wikipedia page!

- ‘The characteristic preference for manipulating objects with the right hand isn’t just a human characteristic. It is found in other primates too‘ – Evidence that right-handedness is common to primates: Forrester, G. S., Quaresmini, C., Leavens, D. A., Mareschal, D., & Thomas, M. S. C. (2013). Human handedness: An inherited evolutionary trait. Behavioural Brain Research, 237, 200-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.037

- ‘An exaggeration of a much longer evolutionary trend towards encouraging the two hemispheres to have slightly different functions and to work in parallel‘ – For more on the evolutionary bias for hemispheric functional specialisation: MacNeilage, P. F., Rogers, L., & Vallortigara, G. (2009, June). Origins of the left and right brain. Scientific American, 301, 160–167.

- ‘Aphasic patients with left hemisphere damage frequently retain the ability to swear‘ – For more on swearing and the right hemisphere, see: Hansen, S. J., McMahon, K. L., & de Zubicaray, G. I. (2019). The neurobiology of taboo language processing: fMRI evidence during spoken word production. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 14(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsz009: They say: “The ability to swear is frequently intact and fluent among aphasic patients (van Lancker and Cummings, 1999). Broca’s (1861) famous patient ‘Leborgne’, often described as only being able to produce the word ‘tan’, in fact augmented his limited speech output with an occasional curse, the oath ‘Sacre nom de Dieu’ (Code, 2013).”

- ‘The processing of space in the right hemisphere appears to be more holistic and integrative … The left hemisphere may be biased to process features and detail‘ – The “Navon task” shows this difference in drawing – adults with left-side damage produce drawings with global patterns but not detail, while adults with right-side damage produce drawings with detail but not global organisation. See: Lamb MR, Robertson LC, Knight RT. Component mechanisms underlying the processing of hierarchically organized patterns: inferences from patients with unilateral cortical lesions. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1990 May;16(3):471-83. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.3.471. PMID: 2140405.

- ‘Perhaps this is achieved by tweaking the range of connectivity in the neural circuits in each hemisphere, shorter connections in the left, longer in the right‘ – We speculate here about what brain properties produce functional specialisation for high-level behaviours. It is still a mystery what the genes are that prompt the consistent hemispheric functional specialisation in primates as a developmental outcome. The genes do not seem to be the same as those that signal location the left and right brain in embryonic development. See: Patric Kienast et al. The Prenatal Origins of Human Brain Asymmetry: Lessons Learned from a Cohort of Fetuses with Body Lateralization Defects, Cerebral Cortex, Volume 31, Issue 8, August 2021, Pages 3713–3722, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab042

- ‘If the left hemisphere is damaged in early childhood in exactly the regions that would cause aphasia in adults, the child can still develop to acquire language skills in the normal range‘ – For more on the effects of focal brain damage on language in children: Bates E, Reilly J, Wulfeck B, Dronkers N, Opie M, Fenson J, Kriz S, Jeffries R, Miller L, Herbst K. Differential effects of unilateral lesions on language production in children and adults. Brain Lang. 2001 Nov;79(2):223-65. doi: 10.1006/brln.2001.2482. PMID: 11712846.

- ‘Similarly for visual attention in childhood, development allows the undamaged hemisphere to contribute to the acquisition of skills in the normal range‘ – For more on visual neglect in children, see: Trauner DA. Hemispatial neglect in young children with early unilateral brain damage. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003 Mar;45(3):160-6. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000318. PMID: 12613771.

- ‘What doesn’t make sense, though, is why the left side of the brain should receive inputs from and control the right side of the body, and vice versa. Where does this ‘contra-lateral’ pattern come from?‘ – The leading theory on how contra-lateral brain organisation evolved is the axial twist hypothesis. This paper lays out the hypothesis and presents direct evidence of the twisting embryo during early development in chicks: de Lussanet, Marc H.E., & Osse, Jan W.M. (2012). An ancestral axial twist explains the contralateral forebrain and the optic chiasm in vertebrates. Animal Biology. 62 (2): 193–216. arXiv:1003.1872. doi:10.1163/157075611X617102. Note, there is a competing hypothesis called the somatic twist, but as you can see, the explanation generally involves twisting.

Living in the future, borrowing from the past

- ‘However, in its awake state, the brain is always in the game, primed for the most likely next move, predicting what it’s likely to see next, getting relevant circuits ready to fire‘ – For the idea that sensory systems bounce around in states near to the most likely next input to accelerate the speed of perception, see: Hartmann C, Lazar A, Nessler B, Triesch J. Where’s the Noise? Key Features of Spontaneous Activity and Neural Variability Arise through Learning in a Deterministic Network. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015 Dec 29;11(12):e1004640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004640. PMID: 26714277; PMCID: PMC4694925.

- ‘predicting what it’s likely to see next‘ – For a detailed exposition of how prediction works through bottom-up and top-down connectivity in the hierarchical visual sensory system, see: Singer W. Recurrent dynamics in the cerebral cortex: Integration of sensory evidence with stored knowledge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Aug 17;118(33):e2101043118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101043118. PMID: 34362837; PMCID: PMC8379985.

- ‘Some of this prediction is about guiding action‘ – For more on cerebellar prediction errors, see: Schlerf, J., Ivry, R. B., & Diedrichsen, J. (2012). Encoding of sensory prediction errors in the human cerebellum. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32(14), 4913–4922. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4504-11.2012

- ‘anticipating the sensory consequences of your actions on your body, and sometimes ignoring them‘ – Some researchers have also argued that the predictive brain explains why we can’t tickle ourselves – because our motor cortex tells our somatosensory cortex that the stimulation was caused by ourselves, so it’s just not funny: Blakemore SJ, Wolpert D, Frith C. Why can’t you tickle yourself? Neuroreport. 2000 Aug 3;11(11):R11-6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00002. PMID: 10943682. Although, that said, oddly enough, you can tickle the roof of your mouth with your tongue. Go on, try it.

- ‘Some of the prediction is about guiding learning. Let’s say you walk into your very own kitchen.’ – The kitchen example is adapted from: Greve, A., Cooper, E., Kaula, A., Anderson, M. C., & Henson, R. (2017). Does prediction error drive one-shot declarative learning? Journal of Memory and Language, Volume 94, 2017, Pages 149-165, ISSN 0749-596X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2016.11.001.

- ‘If you don’t get the balance right, you’ll suffer hallucinations: you’ll see your ideas and not reality… When there is too much dopamine in the system – as is sometimes the case in Parkinson’s Disease when treatment is given to replace missing dopamine – the result can be hallucinations‘ – Source for types of hallucination in Parkinson’s Disease: https://www.parkinson.org/Understanding-Parkinsons/Symptoms/Non-Movement-Symptoms/Hallucinations-Delusions. Here’s a review of what’s known about hallucinations, though it’s still not an entirely clear picture: Kumar S, Soren S, Chaudhury S. Hallucinations: Etiology and clinical implications. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009 Jul;18(2):119-26. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.62273. PMID: 21180490; PMCID: PMC2996210. Recent evidence suggesting that excess striatal dopamine leads to an overestimation of the reliability of expectation, causing hallucinations: Cassidy CM, Balsam PD, Weinstein JJ, Rosengard RJ, Slifstein M, Daw ND, Abi-Dargham A, Horga G. A Perceptual Inference Mechanism for Hallucinations Linked to Striatal Dopamine. Curr Biol. 2018 Feb 19;28(4):503-514.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.12.059. Epub 2018 Feb 2. PMID: 29398218; PMCID: PMC5820222.

- ‘As one individual with autism described it, ‘I began to fear all those unknown paths‘ – The quote on the experience of perception in autism is taken from: Bogdashina, O. (2004). Communication Issues in Autism and Asperger Syndrome, Jessica Kingsley, p.60. The argument that perception in some individuals with autism is insufficiently driven by expectations is presented in Pellicano, E., and Burr, D. (2012). When the world becomes “too real”: a Bayesian explanation of autistic perception. Trends. Cogn. Sci. 16, 504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.08.009.

- The argument that delusions and autism are opposite ends of a predictive / top-down continuum, too much prediction vs. too little, is based on: Andersen BP. Autistic-Like Traits and Positive Schizotypy as Diametric Specializations of the Predictive Mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science. July 2022. doi:10.1177/17456916221075252

- ‘Notably, the hyper-sensitivity does not extend to noises that the individual has generated themselves, because these are predictable‘ – Kanner’s note that autistic children can tolerate self-generated noise: can be found in Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child 2, 217–250. Quote from p.245.

- Magic tricks and their neuroscience explanations: these examples are inspired by: Macknik, S., Martinez-Conde, & Blakeslee, S. (2011). Sleights of mind: What the neuroscience of magic reveals about our brains. Profile Books. See p. 144-7. The book reveals other brain foibles that are exploited in magic, such as in card tricks and mind reading.

- Question: What do you call a magician who has lost the magic? Answer: Ian.

Keeping score

- ‘Part of our happiness is whether we can predict what’s going to happen, or perhaps more importantly, whether we can accurately predict what sized reward we are going to get‘ – For evidence, see: Blain B, Rutledge RB. Momentary subjective well-being depends on learning and not reward. Elife. 2020 Nov 17;9:e57977. doi: 10.7554/eLife.57977. PMID: 33200989; PMCID: PMC7755387.

- ‘Previous happiness fades with time, so our more recent reward prediction errors are weighed more heavily‘ – The ‘non-social’ happiness model combines definite rewards, probabilistic rewards, and reward prediction errors, see p.3 in: Rutledge RB, de Berker AO, Espenhahn S, Dayan P, Dolan RJ. The social contingency of momentary subjective well-being. Nat Commun. 2016 Jun 13;7:11825. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11825. PMID: 27293212; PMCID: PMC4909984.

- ‘What we need is a separate system that represents value in a common currency; and then allows value-based decisions to be made with respect to the demands or preferences of different content-specific systems.‘ – For the proposal that ventromedial prefrontal cortex serves as the broker of value across content-specific systems, ventral tegmental area within striatum serves as the reward and reward prediction calculator, and that there are separate regions for intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, see: Benjamin Chew, Bastien Blain, Raymond J. Dolan, Robb B. Rutledge (2021). A Neurocomputational Model for Intrinsic Reward. Journal of Neuroscience 27 October 2021, 41 (43) 8963-8971; DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0858-20.2021

- ‘Your happiness might go up if you give them some of your stuff to make life fairer‘ – For a neural model of giving, from the perspective of adolescent brain development at least, see Figure 1 in: Eveline A. Crone and Andrew J. Fuligni (2020). Self and Others in Adolescence. Annual Review of Psychology 2020 71:1, 447-469. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050937

- ‘To count other people in your happiness sum‘ – For the ‘social’ happiness model, see p. 4 in: Rutledge RB, de Berker AO, Espenhahn S, Dayan P, Dolan RJ. The social contingency of momentary subjective well-being. Nat Commun. 2016 Jun 13;7:11825. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11825. PMID: 27293212; PMCID: PMC4909984.

- ‘The key to happiness in life is low expectations which can always been exceeded (but not to lower your expectations so much that you’re miserable)‘ – Here’s what the American film director of the LEGO movie, Christopher Miller, had to say on reward prediction errors: “low expectations is the key to happiness in life”. But, added some scientists more recently, don’t lower your expectations so much that you’re miserable: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-9616121/Scientists-suggest-key-HAPPINESS-lowering-expectations.html. Because then you just won’t enjoy the LEGO movie.