How does the brain get to work the way it does? A human starts off as a single fertilised egg, which has to grow into a body and a brain. Does the brain change in the way it works as it grows? What is it that grows anyway since (as we shall see), babies are born with pretty much all the neurons they are ever going to have. What is the difference between development and learning? How do we upload content to our brains? These are the questions we answer in Chapter 7. Once again, here and there we compare the way the brain works and how your mobile phone works. Imagine you unpacked your new mobile phone handset and found in the box just a single silicon chip and a sliver of screen, just a flake of chrome housing. ‘Don’t worry’, say the instructions, ‘it’ll grow into a proper phone, so long as you feed it. And it’ll programme itself, so long as you interact with it and treat it right.’ ‘Oh, um, okay’, you say uncertainly, ‘but will it end up with the correct version of the latest operating system?’ ‘Yeah, definitely, sort of’, reply the instructions, ‘I mean, it depends on what they teach it at phone school.’

Here’s the evidence we refer to in the chapter.

Development:

- ‘Sucking toes is often enthralling‘ – Babies suck their toes, often between 4 and 6 months. Here’s some science on that.

- ‘The brain gets four times bigger from birth to adulthood, but 80% of that growth has already occurred by age two’ – Non-linear brain growth, see e.g., Stiles J, Jernigan TL. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol Rev. 2010 Dec;20(4):327-48. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4. Epub 2010 Nov 3. PMID: 21042938; PMCID: PMC2989000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2989000/

- ‘The average rate of generating neurons prenatally is 250,000 a minute‘ – 250,000 neurons generated per minute, statistic from: Budday S, Steinmann P and Kuhl E (2015) Physical biology of human brain development. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:257. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00257

- ‘Pretty much all the neurons you’re going to get are present in your brain when you’re born (only the hippocampus and olfactory bulb can add new neurons as they go)‘ – Why doesn’t the cortex add extra neurons after birth, only the hippocampus and the olfactory bulb? One possible reason is the way the cortex stores knowledge. Most memory systems encode knowledge across networks of neurons. These ‘distributed’ representations are key to extracting concepts, that is, general representations that pull themes from many instances. Adding in new neurons later won’t be helpful because the new neurons can’t be easily integrated into these distributed codes. The Beatles composed and performed their music as a four-piece – a fifth member added years later won’t easily fit in. The hippocampus, by contrast, encodes instances using ‘localist’ coding not distributed networks – one solo artist per tune. New neurons can be recruited for this purpose because there is a reduced requirement to collaborate with neighbours to store memories of moments. You turn up, you memorise an instance. Fitness fanatics take note: The ability of the hippocampus to generate new neurons also seems to depend on the physical demands placed on the organism. Rodents put on a treadmill generate more new neurons. So, for a better episodic memory, head to the gym (find out more here: Liu PZ, Nusslock R. Exercise-Mediated Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus via BDNF. Front Neurosci. 2018 Feb 7;12:52. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00052.). What about smell, why is the olfactory bulb also able to generate new neurons? The olfactory bulb probably retains the ability to generate new neurons because chemically detecting smells eventually contaminates the sensory neurons, so new ones are required.

- ‘If you put some embryonic neurons in a warm, friendly petri dish, it’s a surprise to see how much they wriggle‘ – Here are some mouse cortical neurons in a dish. See how they reach out and try to connect with each other. Thanks to Ane Goikolea-Vives and Helen Stolp for this video.

- ‘There’s not much in the way of content. For that, you need self-organisation‘ – To find out more about self-organisation and development, see: Sirois S, Spratling M, Thomas MS, Westermann G, Mareschal D, Johnson MH. Précis of neuroconstructivism: how the brain constructs cognition. Behav Brain Sci. 2008 Jun;31(3):321-31; discussion 331-56. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0800407X. PMID: 18578929. Or read the whole book! https://www.amazon.co.uk/Neuroconstructivism-Constructs-Cognition-Developmental-Neuroscience/dp/0198529910. And here’s something more recent: Astle DE, Johnson MH, Akarca D. Toward computational neuroconstructivism: a framework for developmental systems neuroscience. Trends Cogn Sci. 2023 Aug;27(8):726-744. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2023.04.009. Epub 2023 May 31. PMID: 37263856.

- ‘The different levels of the sensory and motor hierarchies are part of the broad wiring diagram, but the hierarchy doesn’t yet have organisation‘ – Re the newly grown hierarchy doesn’t yet have organisation: See work by Ghislaine Dehaene-Lambertz exploring the earliest stages of the language system: Two regions of the brain involved in language processing in adults – Wernicke’s area at the back for language comprehension, and Broca’s area at the front for language production – both show activation as if they are communicating with each other, before the infant has begun to learn language. Dehaene-Lambertz G. The human infant brain: A neural architecture able to learn language. Psychon Bull Rev. 2017 Feb;24(1):48-55. doi: 10.3758/s13423-016-1156-9.. See here for recent work showing how genetic programmes wire up primary sensory and motor cortex, but secondary or higher functional regions in cortex self-organise based on activity – and the larger your cortex (e.g., in human versus mouse), the more functional areas self-organisation produces: Imam N, L Finlay B. Self-organization of cortical areas in the development and evolution of neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Nov 17;117(46):29212-29220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2011724117.

- ‘Recent in evolutionary terms – the hominid brain has tripled in size over the last two million years‘ – The brain has tripled in size over 2 million years: Zhang J. Evolution of the human ASPM gene, a major determinant of brain size. Genetics. 2003 Dec;165(4):2063-70. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.2063. PMID: 14704186; PMCID: PMC1462882.

- ‘A few constant landmarks found across all mammals with larger brains … These landmarks are the primary sensory regions and the primary motor cortex‘ – The few consistent sensory and motor landmarks across larger brained mammals, and the relation of cortical size to cognitive control, from Finlay & Uchiyama (2015). E.g., the advantage of having a bigger brain: ‘In a massive study of some 36 species conducted in multiple laboratories, superior performance on two measures of ‘cognitive control’ was correlated with absolute brain size. In another study of primates alone, the time an individual would wait for a preferred reward was also correlated with absolute brain size … The increasing convergence of hierarchically arranged multiple cortical areas on a frontal lobe, itself hierarchical, may be the direct physical correlate of the ability to compare and decide between behavioural alternatives. The automatic increase in the power of hierarchical organization in larger brains for cognitive control, useful to specialist and generalist alike, and driven by conserved developmental mechanisms, may be the key to understanding the advantage of larger brains in nature.” (p.74-75). Finlay BL, Uchiyama R. Developmental mechanisms channeling cortical evolution. Trends Neurosci. 2015 Feb;38(2):69-76. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.11.004. Epub 2014 Dec 11. PMID: 25497421.

- ‘The post-natal brain overproduces connectivity … and then cuts back the connections that haven’t been used‘ – Timing of grey matter peaks, see: Toga AW, Thompson PM, Sowell ER. Mapping brain maturation. Trends Neurosci. 2006 Mar;29(3):148-59. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.007. Epub 2006 Feb 10. PMID: 16472876; PMCID: PMC3113697.

- ‘This means that the reduction of plasticity linked to optimisation (sometimes referred to as sensitive periods) is mainly a feature of low-level sensory and motor systems‘ – For discussion of sensitive periods and learning: see Thomas, M. S. C. (2012). Brain plasticity and education. British Journal of Educational Psychology – Monograph Series II: Educational Neuroscience, 8, 142-156; and: Knowland, V. C. P., & Thomas, M. S. C. (2014). Educating the adult brain: How the neuroscience of learning can inform educational policy. International Review of Education, 60, 99-122. DOI:10.1007/s11159-014-9412-6

- The immune system may be involved in the pruning process and the immune system can sometimes go wrong. Sometimes it is over-enthusiastic. This may be one cause of schizophrenia: immune-system induced over-pruning in the prefrontal cortex, occurring in late adolescence or early adulthood, disrupts the modulatory system’s control of the posterior content-systems. See (warning, neuroscience is quite heavy duty!): Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, Davis A, Hammond TR, Kamitaki N, Tooley K, Presumey J, Baum M, Van Doren V, Genovese G, Rose SA, Handsaker RE; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Daly MJ, Carroll MC, Stevens B, McCarroll SA. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature. 2016 Feb 11;530(7589):177-83. doi: 10.1038/nature16549. Epub 2016 Jan 27.

- Disruptions to the pruning process may also be implicated in the different cognitive processes associated with autism, causing cortical sensory information to be more detailed and fractionated: Thomas MS, Davis R, Karmiloff-Smith A, Knowland VC, Charman T. The over-pruning hypothesis of autism. Dev Sci. 2016 Mar;19(2):284-305. doi: 10.1111/desc.12303. Epub 2015 Apr 6. PMID: 25845529. pdf.

- Somatosensory cortex may be an exception when it comes to the reduction of plasticity of low-level sensory systems. This is likely because the somatosensory system, which must map the sense of touch across the body surface, has to adjust throughout development while the body surface grows, which can continue throughout the first two decades of life. However, such extended sensory plasticity has also been linked to maladaptive responses, such as the emergence of phantom limbs (and limb pain) following loss of a limb: Andoh J, Milde C, Tsao JW, Flor H. Cortical plasticity as a basis of phantom limb pain: Fact or fiction? Neuroscience. 2018 Sep 1;387:85-91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.11.015. Epub 2017 Nov 16. PMID: 29155276.

- ‘You’ll sometimes hear that. That the teenage brain is radically rewired, that it undergoes a major period of growth and restructuring‘ – Examples of wild claims that the brain rewires / reorganises in adolescence: https://www.turningpointschool.org/middle-school-brain-radical-rewiring/, https://www.fife.gov.uk/kb/docs/articles/education2/supporting-children-in-school/educational-psychology-service/teenagers-brains-and-behaviour, https://www.turningpointschool.org/middle-school-brain-radical-rewiring/

- ‘That’s the press, anyhow.’ – Adolescent behaviour and elevated risk taking: here’s the sort of evidence that supports that characterisation: Saragosa-Harris NM, Cohen AO, Reneau TR, Villano WJ, Heller AS, Hartley CA. Real-World Exploration Increases Across Adolescence and Relates to Affect, Risk Taking, and Social Connectivity. Psychol Sci. 2022 Oct;33(10):1664-1679. doi: 10.1177/09567976221102070. Epub 2022 Sep 14. PMID: 36219573.

- ‘To answer this, let’s take a brief digression to a species where this challenge is writ even larger: the honeybee.’ – Here and in the next four paragraphs are sources for research on the honeybee brain (particularly for the apiarists among you!). Bee brain structures are linked to behaviour rather than age: Mercer, A. R. (2001). The predictable plasticity of honey bees. In Christopher A. Shaw, Jill McEachern (Eds.) Towards a theory of neuroplasticity. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203759790

- Foragers like to be in the light, and changes in bee behaviour are linked to phototaxis (the preference to move towards or away from a light source): Ben-Shahar Y, Leung HT, Pak WL, Sokolowski MB, Robinson GE. cGMP-dependent changes in phototaxis: a possible role for the foraging gene in honey bee division of labor. J Exp Biol. 2003 Jul;206(Pt 14):2507-15. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00442. PMID: 12796464. And: Nouvian, M., Galizia, C.G. Complexity and plasticity in honey bee phototactic behaviour. Sci Rep 10, 7872 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64782-y

- Role of genes in the change of behaviour: Ben-Shahar, Y., Robichon, A., Sokolowski, M.B. & Robinson, G.E. (2002) Behavior influenced by gene action across different time scales. Science 296, 742–744.

- Whitfield, C.W., Cziko, A.M. and Robinson, G.E. (2003) Gene Expression Profiles in the Brain Predict Behavior in Individual Honey Bees. Science, 302, 296-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1086807

- Brain plasticity changes in the shift to foraging: Shapira, M., Thompson, C.K., Soreq, H. et al. Changes in neuronal acetylcholinesterase gene expression and division of labor in honey bee colonies. J Mol Neurosci 17, 1–12 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1385/JMN:17:1:1

- ‘The adolescent brain is not off the rails‘ – For comparison of positive and negative views of adolescent brain development: Crone EA, Dahl RE. Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012 Sep;13(9):636-50. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313. PMID: 22903221.

- ‘These are all maladaptive changes in the do-it or don’t-do-it to change how I feel network, that is, oscillations between the limbic system, the behavioural initiation system, and the reward system‘. What’s this do-it or don’t-do-it to change how you feel network? It’s the fronto-striatal system including dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, supplementary motor area, and associated basal-ganglia structures, including links to limbic structures such as the amygdala. This network has been implicated in a range of neurodevelopmental conditions including Tourette’s syndrome, obsessive compulsive disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, autism, and depression. See: Bradshaw JL, Sheppard DM. The neurodevelopmental frontostriatal disorders: evolutionary adaptiveness and anomalous lateralization. Brain Lang. 2000 Jun 15;73(2):297-320. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2308. PMID: 10856179. Note, since this book was published, the field has moved towards using terminology of differences instead of disorders, and conditions instead of syndromes, distinguishing between neurotypicality and neurodiversity (see Chapter 8).

- ‘On the up elevator stand general and verbal knowledge, creative problem solving and wisdom‘ – Older brains are wiser: Baltes, P. B., and Staudinger, U. M. (2000). Wisdom: A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue towards excellence. America Psychologist, vol.55, pp.122-136.

- ‘Give older adults a simple task like memorising a list of words while walking, and the requirement to do two things at once causes a decline in memorisation to focus on walking‘ – Evidence that walking interferes with memorisation in older adults: Li, K. Z., Lindenberg, U., Freund, A. M., and Baltes, P. B. (2001). Walking while memorizing: Age-related differences in compensatory behavior. Psychological Science, Vol. 12(3), pp.230-237.

- ‘Across adulthood, you can see subtle changes in brain structure. There’s grey matter loss‘ – Observations of reduction in grey matter across adulthood: Resnick SM, Pham DL, Kraut MA, Zonderman AB, Davatzikos C. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults: a shrinking brain. J Neurosci. 2003 Apr 15;23(8):3295-301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03295.2003. PMID: 12716936; PMCID: PMC6742337.

- ‘White matter shows subtle alterations detectable in the fibre tracts linking distant brain regions‘ – Re changes in brain microstructure across adulthood. The fibre tracts showing changes are as follows: the genu of the corpus callosum, connecting the bilateral prefrontal lobes; the corticospinal tract, a major neural tract in the human brain for motor function; the fornix, a C-shaped bundle of fibres inside cerebral hemispheres which is an important output tract of the hippocampus; the superior longitudinal fasciculus connecting posterior lobes to the frontal lobe in each hemisphere, particularly the perisylvian areas (frontal, temporal, and parietal); and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus, a fibre bundle transferring information between the occipital and the temporal lobes. See: Tian L, Ma L. Microstructural Changes of the Human Brain from Early to Mid-Adulthood. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017 Aug 7;11:393. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00393. PMID: 28824398; PMCID: PMC5545923.

- ‘And under the hood, there is a continuing dance between the processes of growth, maintenance, and the regulation of loss‘ – Changes in brain activation with aging, see: Grady CL, Maisog JM, Horwitz B, Ungerleider LG, Mentis MJ, Salerno JA, Pietrini P, Wagner E, Haxby JV (1994) Age-related changes in cortical blood flow activation during visual processing of faces and location. J Neurosci 14:1450–1462. And: Roberto Cabeza, Cheryl L. Grady, Lars Nyberg, Anthony R. McIntosh, Endel Tulving, Shitij Kapur, Janine M. Jennings, Sylvain Houle and Fergus I. M. Craik. (1997). Age-Related Differences in Neural Activity during Memory Encoding and Retrieval: A Positron Emission Tomography Study. Journal of Neuroscience 1 January 1997, 17 (1) 391-400; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00391.1997

- Um, wait, the person’s name will come to me – When memory begins to fail, why is it that the first thing to suffer is the ability to remember people’s names? Names are part of semantic knowledge, which is formed from networks of related meanings (cows, cats, and dogs are all animals; they share some features, four legs, but differ in others, climbing trees). The knowledge is stored in the hub at the top of the visual sensory hierarchy in the front of the temporal lobe. Our ability to retrieve names depends in part how perceptually and semantically distinct a meaning is, as well as how frequently we utilise it. However, people are very perceptually similar to each other (same number of eyes, same body shapes) and have overlapping properties (work colleagues, friends). This makes them both perceptually and semantically confusable, which makes it harder to retain the link to their unique names. This is why when the temporal lobe declines, or is even jet lagged, name retrieval suffers. For more, see: Passingham, R. (2016). Cognitive neuroscience: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p.52-53.

- The adult brain still retains plenty of plasticity. For example, see Braga et al. (2017) for the changes in an adult brain when a previously illiterate 45-year-old Brazilian man learned to read. Braga and colleagues say: “Initially, the participant did not activate neural circuits for reading when he was exposed to words; gradually, however, he began to present activation in left occipitotemporal cortex, at the visual word form area. This increase was accompanied by a decrease in face responses. Reading-related responses also emerged in language-related areas of the inferior frontal gyrus and temporal lobe. Additional activations in superior parietal lobe, superior frontal gyrus and posterior medial frontal cortex suggested that reading remained dependent on effortful executive attention and working memory processes. Nevertheless, the results indicate that adult plasticity can be sufficient to induce rapid changes in brain responses to written words and faces in an unschooled and illiterate adult.” Braga, L.W., Amemiya, E., Tauil, A., Suguieda, D., Lacerda, C., Klein, E., Dehaene-Lambertz, G. and Dehaene, S. (2017), Tracking Adult Literacy Acquisition With Functional MRI: A Single-Case Study. Mind, Brain, and Education, 11: 121-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12143

- The ability to find alternative ways to utilise brain areas to deliver the same behaviour is called cognitive reserve – the brain finds other ways to do things. Can’t remember Mr. Skipper’s name? Remember it rhymes with a smoked fish you have for breakfast, visualise him eating a kipper. There, you’ve automated your name retrieval via support from the visual system! There is a related notion of brain reserve – the amount of neural tissue and its level of integrity that you had to start with, before aging got going. If you have more brain stuff, you can afford to lose more before the loss will affect functioning, thereby staving off the effects of aging for longer. See: Stern Y, Barnes CA, Grady C, Jones RN, Raz N. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience. Neurobiol Aging. 2019 Nov;83:124-129. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.03.022.

Learning:

- ‘The brain can’t help but learn. And yet, learning is such hard work‘ – For exploration of the idea that sometimes learning is too much effort in the context of education, see: Daniel T. Willingham (2021). Why Don’t Students Like School? A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for Your Classroom (2nd Ed). Jossey Bass: A Wiley Imprint.

- ‘Learning has different meanings depending on whether you’re working in education, psychology, or neuroscience‘ – The definition of learning from the teaching perspective was taken from the UK government’s 2019 version of the Early Career Framework for teachers, from the table ‘How Pupils Learn (Standard 2 – Promote good progress)’. Learning as ‘a lasting change in pupils’ capabilities or understanding’ is listed as the first fact that early career teachers need to know about how pupils learn. The definitions of learning in education and psychology were taken from OECD (2007) Understanding the Brain: The Birth of a Learning Science. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Page 212: “From a psychological perspective, learning can be defined as a change in the efficiency or use of basic cognitive processes, both conscious and unconscious, that promotes more effective problem solving and performance in the tasks of everyday life… From an educational point of view learning also has to be regarded in its relation to action in the world. Learning therefore not only concerns an expansion of knowledge but also a change in action patterns”

- ‘Let’s begin by getting a sense of why learning is hard. There’s an old science fiction film called The Matrix‘ – Here’s a YouTube clip of how skill learning works in The Matrix: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOZnP4dZYK0

- ‘Famously, the brain can be blind to information entering the senses which are not the focus of attention (because it is engaged on another task)‘ – Take the inattention blindness test: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo: task, count how many basketball passes the white team makes.

- Read the paper at: Simons, Daniel J.; Chabris, Christopher F. (1999). Gorillas in our midst: sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception. 28 (9): 1059–1074. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.65.8130. doi:10.1068/p2952. PMID 10694957.

- ‘The dinner bell goes and your tummy rumbles expectantly. This is called classical conditioning‘ – For the role of nucleus basalis in classical conditioning, see: Weinberger NM. The nucleus basalis and memory codes: auditory cortical plasticity and the induction of specific, associative behavioral memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003 Nov;80(3):268-84. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00072-8. PMID: 14521869. And: Guo W, Robert B, Polley DB. The Cholinergic Basal Forebrain Links Auditory Stimuli with Delayed Reinforcement to Support Learning. Neuron. 2019 Sep 25;103(6):1164-1177.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.06.024. Epub 2019 Jul 24. PMID: 31351757; PMCID: PMC7927272.

- ‘Mental effort. It turns out that mental effort costs, and the brain doesn’t like paying.’ – For more on learning and mental effort. Friendly version: Kramer A-W, Huizenga HM, Krabbendam L and van Duijvenvoorde ACK (2020) Is It Worth It? How Your Brain Decides to Make an Effort. Front. Young Minds 8:73. doi: 10.3389/frym.2020.00073. Less friendly version: Asako Mitsuto Nagase, Keiichi Onoda, Jerome Clifford Foo, Tomoki Haji, Rei Akaishi, Shuhei Yamaguchi, Katsuyuki Sakai and Kenji Morita. Neural Mechanisms for Adaptive Learned Avoidance of Mental Effort. Journal of Neuroscience 7 March 2018, 38 (10) 2631-2651; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1995-17.2018.

- ‘Why should mental effort cost? One idea is that activities that involve extended use of the … prefrontal cortex … leads to build up of toxic neurotransmitter metabolites‘ – For more on what might be costly about mental effort: Wiehler A, Branzoli F, Adanyeguh I, Mochel F, Pessiglione M. A neuro-metabolic account of why daylong cognitive work alters the control of economic decisions. Curr Biol. 2022 Aug 22;32(16):3564-3575.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.07.010. Epub 2022 Aug 11. PMID: 35961314;

- ‘[Mental effort] is unlike physical effort, where part of getting fit is to learn how hard you can push yourself‘ – For debates on how the brain regulates physical effort, see: Inzlicht M, Marcora SM. The Central Governor Model of Exercise Regulation Teaches Us Precious Little about the Nature of Mental Fatigue and Self-Control Failure. Front Psychol. 2016 May 4;7:656. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00656. PMID: 27199874; PMCID: PMC4854881.

- ‘Conceptual memory by contrast, finds it harder to learn information that is inconsistent with its previous knowledge‘ – For evidence on how inconsistent conceptual knowledge is harder to learn: van Kesteren MT, Rijpkema M, Ruiter DJ, Morris RG, Fernández G. Building on prior knowledge: schema-dependent encoding processes relate to academic performance. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014 Oct;26(10):2250-61. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00630. Epub 2014 Apr 4. PMID: 24702454.

- ‘Eight interacting mechanisms of learning, then. And each has a preferred diet of experience that will optimise how abilities and knowledge change.’ – To illustrate the idea that different learning systems require different diets of experience, let’s take a concrete example. For children with speech and language difficulties, therapists often help the children with behavioural training to target and improve different language skills. Therapists might target phonology (speech sounds), which relies on perceptual systems (the auditory hierarchy). They might target syntax (grammar), which relies on the procedural learning system for automated sequencing. They might target vocabulary, which relies on the conceptual system and the retrieval of declarative knowledge (the anterior temporal lobe hub). One report by Lindsay and colleagues summarised the evidence of what diet of experience worked best for improving each skill. For phonology, intensive interventions were more effective than those of long duration. For those targeting syntax, interventions of long duration were more effective than short intensive ones. For vocabulary, long duration was important but not intensity – children did better with short bursts over an extended time. The rate-limited aspect of learning was investigated by Smith-Lock and colleagues. In a grammar treatment, they found that the same dose of 8 hours of training was more effective delivered weekly over 8 consecutive weeks than daily over 8 consecutive days. These differences in optimal regimes for intervention reflect the preferred diet of experience for different learning mechanisms, as well as time for consolidation and opportunities for practice. Evidence sources: Lindsay and colleagues: Lindsay, G., Dockrell, J. E., Law, J., Roulstone, S., & Vignoles, A. (2010). Better communication research programme: First interim report. Research report DFE-RR070. London, UK: Department for Education. Smith-Lock and colleagues: Smith-Lock, K., Leitão, S., Lambert, L., Prior, P., Dunn, A., Cronje, J., … Nickels, L. (2013). Daily or weekly? The role of treatment frequency in the effectiveness of grammar treatment for children with specific language impairment. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 255–267. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.777851. Discussion of learning mechanisms and intervention: Thomas, M. S. C., Fedor, A., Davis, R., Yang, J., Alireza, H., Charman, T., Masterson, J., & Best, W. (2019). Computational modelling of interventions for developmental disorders. Psychological Review, 26(5), 693-726. doi: 10.1037/rev0000151.

- ‘The brain also has an overarching principle: Try to make all processes automatic‘ – For evidence on automaticity, executive loops, motor loops, and the basal ganglia: Seger CA, Spiering BJ. A critical review of habit learning and the Basal Ganglia. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011 Aug 30;5:66. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00066. PMID: 21909324; PMCID: PMC3163829

- ‘In the limbic system, the amygdala doesn’t readily forget what situations it finds threatening … the only way to get rid of this information is to actively overwrite it‘ – For more on how to erase fearful memories (fear extinction), see: Quirk GJ, Paré D, Richardson R, Herry C, Monfils MH, Schiller D, Vicentic A. Erasing fear memories with extinction training. J Neurosci. 2010 Nov 10;30(45):14993-7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4268-10.2010. PMID: 21068303; PMCID: PMC3380534.

- The brain can take advantage of its widespread circuits for perceiving and understanding other people to learn skills by observation, so-called ‘modelling’. Michael Jackson … pioneered a dance called moonwalking‘ – See lots of people moonwalking on TikTok (go on, watch the compilation and try to copy the moves!): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IFRMrUjEI7Y

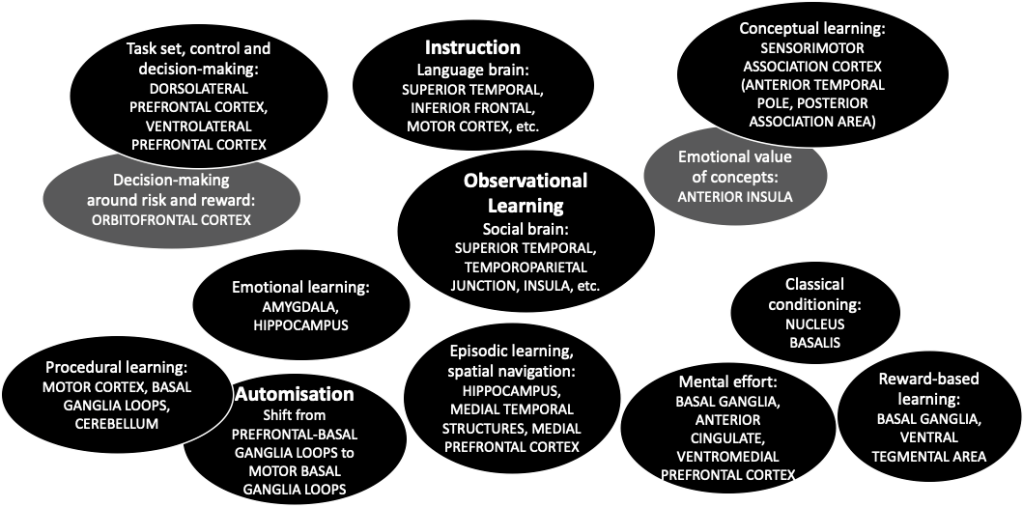

- Here’s a bubble diagram pulling together all the bits of the brain involved in ‘learning’:

- ‘So, we say to the teacher standing in the front of the class of thirty students, good luck with that. (Perhaps that is too pessimistic. We have, after all, written another book on how to use knowledge of how the brain works to help with teaching!)‘ – Here’s our book on using knowledge of how the brain works to improve teaching, written with Cathy Rogers: Rogers, C., & Thomas, M. S. C. (2022). Educational Neuroscience: The Basics. Routledge: London, UK. ISBN 13: 978-1032028552