This chapter considers how brains might work differently in different individuals. We consider what in the brain corresponds to dimensions such as intelligence and personality, and from where these differences might originate (sometimes referred to as the nature/nurture problem). We consider larger scale variations, in the form of developmental conditions (sometimes with disabilities) and giftedness. We consider changes in behaviour caused by acquired brain damage. And we consider what happens when the functional dynamics of the brain are disrupted in psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia and depression. Sometimes these mental health conditions have been explained in terms of alterations to neurotransmitter systems. Does that kind of explanation really work? How does it link to the effectiveness (or not) of drugs that target neurotransmitter systems?

- ‘The main difference between brains is their size‘ – Average human brain taken from this article comparing human and Neanderthal brains: https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/neanderthal-brains-bigger-not-necessarily-better. Range taken from Christopher Koch’s 2016 Scientific American article “Does brain size matter”: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/does-brain-size-matter1. Here’s another paper that gives a range of variation in human brains, this time in a comparison to other species. 36 male and female brains 16-21 years old varied from 1,035cm3 to 1,712cm3: Charvet CJ, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Variation in human brains may facilitate evolutionary change toward a limited range of phenotypes. Brain Behav Evol. 2013;81(2):74-85. doi: 10.1159/000345940.

- ‘Male brains are around 11% bigger than female brains, in line with differences in the sizes of male and female bodies‘ – Recent meta-analysis of sex differences in brain structure and function: Eliot L, Ahmed A, Khan H, Patel J. Dump the “dimorphism”: Comprehensive synthesis of human brain studies reveals few male-female differences beyond size. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021 Jun;125:667-697. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.026.

- ‘There are two main dimensions across which brain function differs. The first is what psychologists call intelligence. The second is what psychologists call personality. They seem to be largely independent sorts of variation‘ – Intelligence and personality are independent: Stankov L. Low Correlations between Intelligence and Big Five Personality Traits: Need to Broaden the Domain of Personality. J Intell. 2018 May 1;6(2):26. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence6020026.

- ‘Having a bigger brain explains about 10% of the variation in intelligence, so maybe just having more cortical neurons does the job‘ – In their study of variations in human brain size, Charvet and colleagues estimated that extended the developmental phase of generation of neurons by between 7 and 8 days would produce the difference in the range of overall brain sizes they observed in their sample of humans. They pointed out that for reference, the total time from conception to the end of generating cortical neurons is 110-120 days in humans. Charvet CJ, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Variation in human brains may facilitate evolutionary change toward a limited range of phenotypes. Brain Behav Evol. 2013;81(2):74-85. doi: 10.1159/000345940.

- ‘Some argue that ‘general’ cognitive ability comes from a ‘general’ mechanism‘ – Domain-general mechanism accounts of general intelligence, see: Deary, I.J., Cox, S.R. & Hill, W.D. Genetic variation, brain, and intelligence differences. Mol Psychiatry 27, 335–353 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01027-y

- ‘Genetic research also points to the contribution of many different low-level properties‘ – Genetics points to multiple low-level properties underlying intelligence: Hill WD, Marioni RE, Maghzian O, Ritchie SJ, Hagenaars SP, McIntosh AM, Gale CR, Davies G, Deary IJ. A combined analysis of genetically correlated traits identifies 187 loci and a role for neurogenesis and myelination in intelligence. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Feb;24(2):169-181. doi: 10.1038/s41380-017-0001-5.

- ‘Similar dimensions of behaviour are seen in other social primates such as chimpanzees’ – These dimensions are also linked to limbic brain structures in primates: Latzman, R., Boysen, S., & Schapiro, S. (2018). Neuroanatomical Correlates of Hierarchical Personality Traits in Chimpanzees: Associations with Limbic Structures. Personality Neuroscience, 1, E4. doi:10.1017/pen.2018.1

- For example, here’s a paper on the role of the amygdala in aggression: Siever LJ. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Apr;165(4):429-42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111774.

- And one on the role of the hippocampus in novelty detection: Kafkas A, Montaldi D. How do memory systems detect and respond to novelty? Neurosci Lett. 2018 Jul 27;680:60-68. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.01.053.

- ‘The monogamy of the prairie vole over the polygamy of the otherwise highly similar montane vole involves more receptors for oxytocin‘ – Oxytocin differences in receptor distribution in prairie vs. meadow voles. Notably, this is in the form of differences across both appetitive and rewards structures: T. James Matthews, Dominique A. Williams, Liana Schweiger (2013). Social Motivation and Residential Style in Prairie and Meadow Voles. The Open Behavioral Science Journal, 2013, 7: 16-23. And: Insel TR, Shapiro LE. Oxytocin receptor distribution reflects social organization in monogamous and polygamous voles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Jul 1;89(13):5981-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5981.

- ‘Exactly how the tuning of different sub-cortical structures produces personality types is still being figured out‘ – We discuss the role of hormones and neurotransmitters in tuning sub-cortical systems to alter personality. The vole example is relevant to variations in human personality if we assume that the variation observed between species is echoed by variation within species. We have some grounds for this view, since this assumption is necessary for new species to evolve out of old, and it is supported by the brain morphometry patterns (see the Brain-maker-5000) discussed in Chapter 3. The same scaling rules for the size of parts of the brain across mammalian species also hold for variations within primate species.

- Voles are a nice example of the role of neurohormonal regulation tuning behaviour but not the only one. A recent comparison by Qi et al. (2023) across Asian colobine primates, a set of closely related monkey species, explored the genetic differences associated with variations in the complexity of their social systems across species, from solitary living to large multi-level societies. The study concluded that more complex social systems emerged in species that were adapted to cold climates, where co-operative behaviour is more important for survival. Crucially, the increase in social complexity may have been triggered through selection of gene variants to promote maternal care in nurturing babies in cold conditions. The authors found that “glacial periods during the past 6 million years promoted the selection of genes involved in cold-related energy metabolism and neurohormonal regulation. More-efficient dopamine and oxytocin pathways developed in odd-nosed monkeys, which may have favoured the prolongation of maternal care and lactation, increasing infant survival in cold environments. These adaptive changes appear to have strengthened inter-individual affiliation, increased male-male tolerance, and facilitated the stepwise aggregation from independent one-male groups to large multilevel societies.” Once more, we see the involvement in tuning appetitive and reward systems in driving the emergence of complex behaviour. (Qi XG, Wu J, Zhao L, Wang L, Guang X, Garber PA, Opie C, Yuan Y, Diao R, Li G, Wang K, Pan R, Ji W, Sun H, Huang ZP, Xu C, Witarto AB, Jia R, Zhang C, Deng C, Qiu Q, Zhang G, Grueter CC, Wu D, Li B. Adaptations to a cold climate promoted social evolution in Asian colobine primates. Science. 2023 Jun 2;380(6648):eabl8621. doi: 10.1126/science.abl8621.)

- ‘So the tuning that represents different personality types will likely involve a range of the systems we have encountered before‘ – Here are some examples of papers figuring out what brain differences line up with what personality types (though these two papers measure the size of structures, which is probably not quite the best place to look since personality differences will tune the functionality of the relevant structures): DeYoung CG, Hirsh JB, Shane MS, Papademetris X, Rajeevan N, Gray JR. Testing predictions from personality neuroscience. Brain structure and the big five. Psychol Sci. 2010 Jun;21(6):820-8. doi: 10.1177/0956797610370159. And: Wright CI, Williams D, Feczko E, Barrett LF, Dickerson BC, Schwartz CE, Wedig MM. Neuroanatomical correlates of extraversion and neuroticism. Cereb Cortex. 2006 Dec;16(12):1809-19. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj118.

Nature or nurture?

- ‘Let’s say that of the tenth of a percentage point of DNA that varies between humans‘ – Statistic that 0.1% of the human genome varies between humans, stat taken from: https://www.genome.gov/dna-day/15-ways/human-genomic-variation

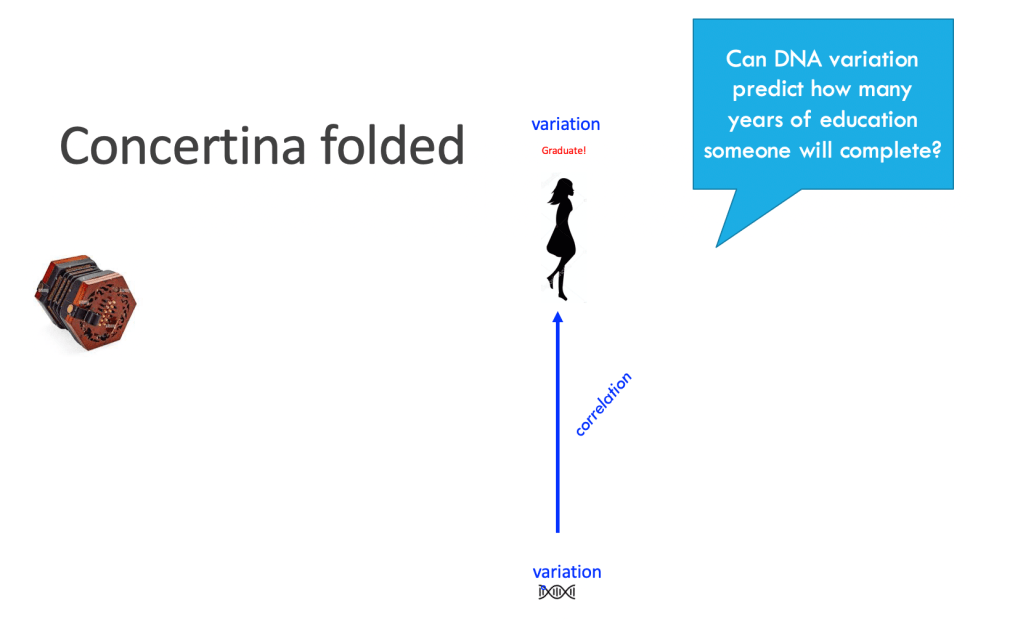

- ‘But behaviour itself comes from a long chain of interactions with the world as you develop‘ – Let’s illustrate this idea with an example we call the causal concertina. A concertina is an instrument whose sound is generated by stretching and squeezing a central bellows, but here, trust us, we’re using it as a metaphor.

- Let’s consider correlating genetic variation, perhaps even of individual letters of DNA, with how many years you spend in education, like these guys do. We can think of this as a correlation when the concertina is squeezed and so the developmental process is hidden in the folds.

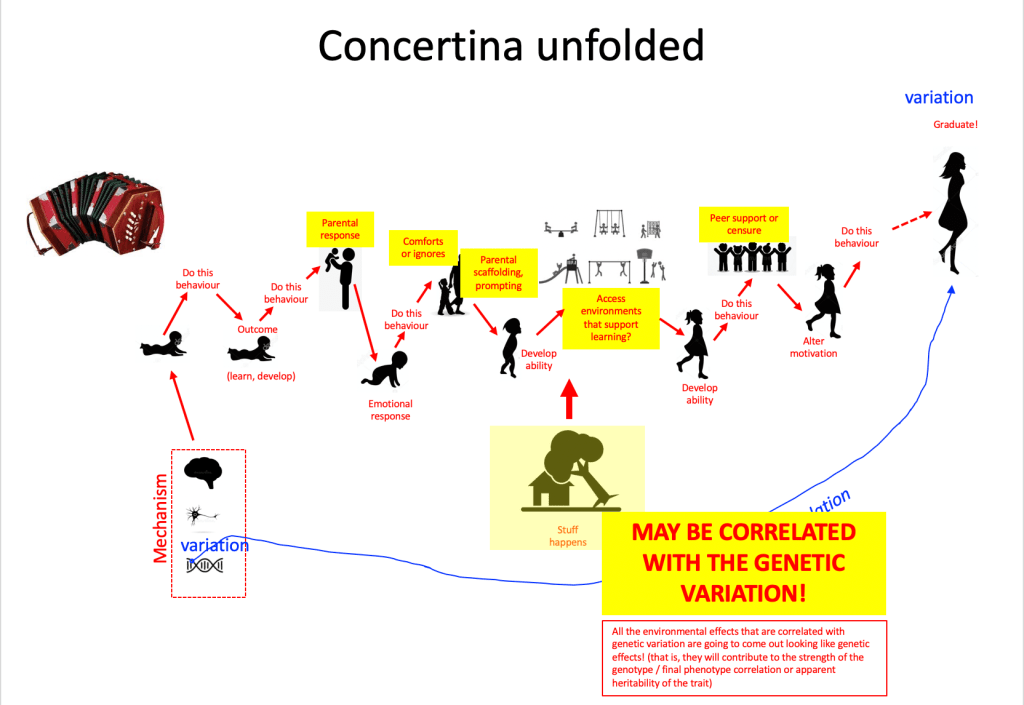

- Now let’s stretch the concertina, and unfold all the developmental interactions with the environment, physical, with home, playground, and school environments, social, with caregivers and peers; add in the circumstances and events that may affect an individual, as their dreams are buoyed on clouds of hope or dashed on the rocks of misfortune…

- For sure, you can still run that correlation between genetic variation and final educational attainment, but now you can see how far you are reaching across development, and how many interactions with the environment you are collapsing over. Crucially, a bunch of those environments you interact with (those shown in yellow below) are likely to be correlated somewhat with your genetic variation. For example, how your parents react to your behaviour (comfort you or scold you) – they share your genes; the richness of your home or neighbourhood resources – they in part reflect your parents’ station in life, partly influenced by their genes, which you share; the peer group you choose for yourself (party people or thoughtful discussion group) – your choices are partly influenced by your genes. Together, this means that contributions of genetic variation to brain development or function become thoroughly entwined with environmental influences across lifespans. Yes, it’s true, the measured genetic variation may seem to predict half of the variation in outcomes when the concertina is folded, but this hides a complex web of developmental processes.

- Shifting to the environmental side for a moment, one factor we can measure that seems to predict variation in brain development is family socioeconomic status (SES). SES indexes a range of differences that track with families who are struggling economically or who are more prosperous, such as parental education and family income. It is a well-studied environmental factor observed to affect children’s development. In a large enough sample of children (over a thousand), small differences in the thickness of the cortex were found to correlate with SES levels, with stronger effects seen in the temporal and frontal lobes. Higher SES was associated with slightly thicker cortex. Noble KG, Houston SM, Brito NH, Bartsch H, Kan E, Kuperman JM, Akshoomoff N, Amaral DG, Bloss CS, Libiger O, Schork NJ, Murray SS, Casey BJ, Chang L, Ernst TM, Frazier JA, Gruen JR, Kennedy DN, Van Zijl P, Mostofsky S, Kaufmann WE, Kenet T, Dale AM, Jernigan TL, Sowell ER. Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nat Neurosci. 2015 May;18(5):773-8. doi: 10.1038/nn.3983.

- However, the functional implications of these structural differences are less clear: Farah MJ. The Neuroscience of Socioeconomic Status: Correlates, Causes, and Consequences. Neuron. 2017 Sep 27;96(1):56-71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.034. Models of the mechanisms influenced by variations in SES are needed to test out the possibilities: Thomas, M. S. C., & Coecke, S. (2023). Associations between socioeconomic status, cognition and brain structure: Evaluating potential causal pathways through mechanistic models of development. Cognitive Science. DOI:10.1111/cogs.13217

- ‘There’s a theorem in statistics which stipulates that simply by adding together lots of small effects, you end up with [a normal] distribution‘ – The statistical theorem that you get a bell-shaped curve by adding together enough random variables is called the Central limit theorem. Here’s one version: Let x1, x2, …, xn be a sequence of random variables that are identically and independently distributed, with mean of 0 and variance B2 . Let the sum Sn = 1/sqrt(n)(x1+…+xn). Then the distribution of the normalized sum, Sn, approaches the normal distribution, N(0,B2), as n goes to infinity. In other words, team, add together enough random variables, whatever their individual distributions, and the sum takes on a normal distribution! See Lyon, A. (2014). Why are Normal Distributions Normal? The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 2014 65:3, 621-649. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axs046

- ‘genetic similarity explains about half the variation in intelligence (maybe a little bit higher) and about half the variation in personality (maybe a little bit lower)‘ – Estimate of heritability of intelligence from Deary et al. 2022: Deary IJ, Cox SR, Hill WD. Genetic variation, brain, and intelligence differences. Mol Psychiatry. 2022 Jan;27(1):335-353. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01027-y.

- Estimate of heritability of personality at 40%: Vukasović T, Bratko D. Heritability of personality: A meta-analysis of behavior genetic studies. Psychol Bull. 2015 Jul;141(4):769-85. doi: 10.1037/bul0000017.

- Estimate of heritability of brain structure versus function: Jansen, A.G., Mous, S.E., White, T. et al. What Twin Studies Tell Us About the Heritability of Brain Development, Morphology, and Function: A Review. Neuropsychol Rev 25, 27–46 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-015-9278-9

- Heritability of all traits is about 50%: Polderman TJ, Benyamin B, de Leeuw CA, Sullivan PF, van Bochoven A, Visscher PM, Posthuma D. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet. 2015 Jul;47(7):702-9. doi: 10.1038/ng.3285. Epub 2015 May 18. PMID: 25985137.

- The heritability of intelligence is probably not just a human thing. For example, general cognitive ability appears to be heritable in chimpanzees, too: Hopkins WD, Russell JL, Schaeffer J. Chimpanzee intelligence is heritable. Curr Biol. 2014 Jul 21;24(14):1649-1652. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.076.

- ‘When we deliberately try to breed for certain behaviours in mice’: DeFries JC, Gervais MC, Thomas EA. Response to 30 generations of selection for open-field activity in laboratory mice. Behav Genet. 1978 Jan;8(1):3-13. doi: 10.1007/BF01067700. PMID: 637827.

- ‘This points to one of the major findings in the genetics of human behaviour – that variation in behaviour is associated with variations in many, many bits of DNA‘ – Influence of genetic variation on behaviour is polygenic: Plomin R, DeFries JC, Knopik VS, Neiderhiser JM. Top 10 Replicated Findings From Behavioral Genetics. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2016 Jan;11(1):3-23. doi: 10.1177/1745691615617439.

- Here’s a fun example that illustrates the polygenic version intelligence – i.e., the accumulation of lots of small differences. It’s possible for all your kids to be genetically smarter than you and your partner. (Hey, or more stupid. Biology doesn’t care). Let’s say you have a mixed deck of red and black playing cards. This is an analogy for your genes! Your partner has a similar pack of cards. The black cards each tend to make you a tiny bit more intelligent, the red cards a tiny bit less. Let’s say you have both been dealt roughly even numbers of red and black cards in your packs, which makes you both averagely intelligent. When you have kids, you and your partner each select a random set of 50% of your cards to go into each gamete (egg or sperm). These then get put those together to make a baby (imagine soft lighting, romantic music). So, each of your children gets a random 50% of your cards and a random 50% of your partner’s cards. Just by chance, your 50% could have a majority of black cards. And so, just by chance, could the set selected from your partner. Your child will end up with a majority of black cards, even though you and your partner had about equal red and black cards. This would mean your child would be cleverer than you (at least, from the genetic side). On average that won’t happen. But it sometimes it does. And it could happen for all your kids. Sometimes it’s tough being a parent.

- ‘the average level of intelligence can appear to rise from generation to generation‘ – the Flynn effect. See Flynn, J. R. (2007). What is intelligence? Cambridge University Press. Note, technically the increase in intelligence scores between generations in the 20th century is a group difference, not an individual difference. And importantly, the causes of group differences can be different from individual differences (if that is not too many different differences for you). For example, differences between groups can arise for an environmental reason, even while differences within the groups can still be mostly heritable, due to genetic differences. So, group A can have higher intelligence than group B for an environmental reason (say, an authoritarian government doesn’t allow group B to go to school); but within both group A and group B, differences in intelligence may be heritable. Behavioural genetics is confusing like that. As well as changes in health and diet over the last century, the Flynn effect probably represents an alteration of education systems to focus on teaching kids the kinds of abstract reasoning skills that intelligence tests measure rather than, say, mending ploughs. And these days we may indeed, as a generation, have poorer plough mending skills compared to when IQ scores were first measured. Some things go up, some things go down. Societies decide what skills they will give to their children through education, and raises or lowers the population distribution (and hence average level) of the skills that the next generation acquires.

Back to sex for a moment

- ‘It tells us that female and male brains have slightly different ways of working‘ – Compensatory brain differences between sexes: Deary IJ, Cox SR, Hill WD. Genetic variation, brain, and intelligence differences. Mol Psychiatry. 2022 Jan;27(1):335-353. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01027-y.

- ‘apart from the overall differences in size … there’s almost no difference between male and female brains‘ – No sex differences in macro brain structure other than size (brains scale with body size): van Eijk L, Zhu D, Couvy-Duchesne B, Strike LT, Lee AJ, Hansell NK, Thompson PM, de Zubicaray GI, McMahon KL, Wright MJ, Zietsch BP. Are Sex Differences in Human Brain Structure Associated With Sex Differences in Behavior? Psychol Sci. 2021 Aug;32(8):1183-1197. doi: 10.1177/0956797621996664.

- ‘Male/female brain differences appear trivial and population-specific’: Lise Eliot, Adnan Ahmed, Hiba Khan, Julie Patel. Dump the ‘dimorphism’: Comprehensive synthesis of human brain studies reveals few male-female differences beyond size. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2021; 125: 667 DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.026

- ‘sex differences can be seen in neurons‘ – Male and female neurons have different morphology – these are mouse data: Keil, K.P., Sethi, S., Wilson, M.D. et al. In vivo and in vitro sex differences in the dendritic morphology of developing murine hippocampal and cortical neurons. Sci Rep 7, 8486 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08459-z. See also Goikolea-Vives, A. (2022). Development and plasticity of structural and functional neural networks in the mouse brain. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Royal Veterinary College, University of London, UK.

- ‘inhibitory GABAergic neurons have receptors for oestrogen and progesterone‘ – Inhibitory GABAergic neurons have receptors for female sex hormones: Thind KK, Goldsmith PC. Expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in glutamate and GABA neurons of the pubertal female monkey hypothalamus. Neuroendocrinology. 1997 May;65(5):314-24. doi: 10.1159/000127190. .

When variations are larger

- Differences in gross brain anatomy in genetic syndromes: Down syndrome: Pinter JD, Eliez S, Schmitt JE, Capone GT, Reiss AL. Neuroanatomy of Down’s syndrome: a high-resolution MRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001 Oct;158(10):1659-65. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1659. PMID: 11578999.

- Williams syndrome: Reiss AL, Eliez S, Schmitt JE, Straus E, Lai Z, Jones W, Bellugi U. IV. Neuroanatomy of Williams syndrome: a high-resolution MRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12 Suppl 1:65-73. doi: 10.1162/089892900561986. PMID: 10953234.

- Fragile X: Hoeft F, Carter JC, Lightbody AA, Cody Hazlett H, Piven J, Reiss AL. Region-specific alterations in brain development in one- to three-year-old boys with fragile X syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 May 18;107(20):9335-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002762107. Epub 2010 May 3. PMID: 20439717; PMCID: PMC2889103.

- An example of a study showing different brain chemistry in a genetic syndrome, in this case Williams syndrome: Millichap, J.G., 1998. Cerebellar MR Spectroscopy in Williams Syndrome. Pediatric Neurology Briefs, 12(8), pp.63–64. DOI: http://doi.org/10.15844/pedneurbriefs-12-8-11

- Survival to term of having trisomy of different autosomal (non-sex) chromosomes: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aneuploidy. Aneuploidy means the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell.

- In our discussion of developmental conditions, we’re not considering sensory impairment, blindness, deafness, congenital growth problems with the body or its peripheral nervous system. We regrettably can’t cover everything, and our focus in the book was on how the brain (central nervous system) can work differently. Nevertheless, sensory impairments and changes in the body can cause functional reorganisation in the CNS during development as, for example, the neural tissue normally enervated by missing sensory information is repurposed into other functions.

- ‘Most of the variation in cortical development is likely to be general across the cortical sheet’: Deary, I.J., Cox, S.R. & Hill, W.D. Genetic variation, brain, and intelligence differences. Mol Psychiatry 27, 335–353 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01027-y: They say, ‘Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variation associated with intelligence has been linked to tissue-specific gene expression in specific classes of neuron, including pyramidal neurons of the somatosensory cortex, the CA1 region of the hippocampus, midbrain embryonic GABAergic neurons, and medium spiny neurons. These associations indicate that, rather than any one specific area, the association between genetic and intelligence variation is probably mediated in part by individual differences in gene expression across the cortex. Genetic variants associated with intelligence test scores tend to cluster in groups of genes linked with neurogenesis, the synapse, neuron differentiation, and oligodendrocyte differentiation’ (p.341).

- ‘However, there must be some regional differences in how the cortex is impacted to produce uneven cognitive profiles’: – See for example, Grasby KL, et al The genetic architecture of the human cerebral cortex. Science. 2020 Mar 20;367(6484):eaay6690. doi: 10.1126/science.aay6690. They say, ‘We show that the genetic architecture of the cortex is highly polygenic and that variants often have a specific effect on individual cortical regions. This finding suggests that there are distinct genes involved in the development of specific cortical areas and raises the possibility of developmental and regional specificity in expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) effects. We also find that rare variants and common variants in similar locations in the genome can lead to similar effects on brain structure, albeit to different degrees.’ (p. 6-7). Grasby et al. commented that regional effects appeared associated with genetic pathways linked to progenitor expansion (generating neurons for certain regions) and areal identity (chemical signals to tell neurons how to behave when in particular regions).

- While it is likely that regional differences produce uneven cognitive profiles in neurodevelopmental conditions, it could also be that more widespread differences are involved but impact on a processing / biological properties upon which a certain skill particularly relies, so-called domain-relevant properties. Karmiloff-Smith (1998) illustrated this possibility with a striking example of how a body-wide genetic effect nevertheless produced a very specific outcome of hereditary early acquired deafness: “Geneticists studying eight generations of a Costa Rican family found a 50% incidence of acquired deafness, with onset around age 10 and complete deafness by age 30. A single gene mutation was identified, with the last 52 amino acids in the gene’s protein product mis-formed, and the first 1,213 amino acids formed correctly. This gene produces a protein that controls the assembly of actin. Actin organizes the tiny fibres found in cell plasma which determine a cell’s structural properties, such as rigidity. Because the genetic impairment is tiny and the protein functions sufficiently well to control the assembly of actin in most parts of the body, no other deficits are observable. However, it turns out that hair cells are especially sensitive to loss of rigidity, such that even this tiny impairment has a huge effect on them, resulting in deafness. In other words, what might look like a specialized gene for a complex trait like hearing is, on closer examination, very indirect – hearing is dependent on the interaction of huge numbers of genes, one of which affects the rigidity of hair cells and has cascading effects on the others.” (p.392). Karmiloff-Smith A. Development itself is the key to understanding developmental disorders. Trends Cogn Sci. 1998 Oct 1;2(10):389-98. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01230-3. PMID: 21227254. Work referred to: Lynch, E.D. et al. (1997) Nonsyndromic deafness DFNA1 associated with mutation of a human homolog of the Drosophila gene diaphanous Science, 278, 1315–1318.

- Cortical regions and behaviourally defined conditions (though note, in most cases, subtle differences in multiple areas are observed):

- DLD, dyslexia and the temporal lobes: Richlan F. Developmental dyslexia: dysfunction of a left hemisphere reading network. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 May 1;6:120. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00120; Lee JC, Dick AS, Tomblin JB. Altered brain structures in the dorsal and ventral language pathways in individuals with and without developmental language disorder (DLD). Brain Imaging Behav. 2020 Dec;14(6):2569-2586. doi: 10.1007/s11682-019-00209-1.

- Congenital amusia and the temporal lobes (frontal cortex also implicated): Chen J, Yuan J. The Neural Causes of Congenital Amusia. J Neurosci. 2016 Jul 27;36(30):7803-4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1500-16.2016. Developmental coordination disorder / dyspraxia and frontal cortex: Biotteau M, Chaix Y, Blais M, Tallet J, Péran P, Albaret JM. Neural Signature of DCD: A Critical Review of MRI Neuroimaging Studies. Front Neurol. 2016 Dec 16;7:227. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00227.

- Dyscalculia the parietal lobe: McCaskey U, von Aster M, O’Gorman R, Kucian K. Persistent Differences in Brain Structure in Developmental Dyscalculia: A Longitudinal Morphometry Study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020 Jul 17;14:272. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.00272.

- ADHD and the frontal lobes: Gehricke JG, Kruggel F, Thampipop T, Alejo SD, Tatos E, Fallon J, Muftuler LT. The brain anatomy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in young adults – a magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS One. 2017 Apr 13;12(4):e0175433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175433.

- One might expect that regional effects to sensory lobes would impact on primary perception rather than just higher-level skills like language or attention; or that regional effects on the frontal cortex would manifest in profound motor deficits. However, where primary perceptual deficits are observed, these don’t seem to be associated with developmental differences in cortical systems, rather with lower-level anomalies in the mid-brain and brain stem (though more subtle cortical anomalies might feed through to higher level problems, such as in language disorders): Hans J. ten Donkelaar, Martin Lammens, Johannes R.M. Cruysberg and Cor W.J.R. Cremers (2006). Development and Developmental Disorders of the Brain Stem. In Hans J. Donkelaar, Martin Lammens, Akira Hori (Eds.) Clinical Neuroembryology: Development and Developmental Disorders of the Human Central Nervous System (p. 321-370). Springer. DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-54687-7_7

- Severe developmental motor problems, such as in cerebral palsy, are caused by a range of brain differences, including cortical damage to motor areas, damage to sub-cortical and cerebellar structures, but also widespread damage in white matter and grey matter. Cerebral palsy can be divided into individuals whose brain injury occurred during the gestational period, during delivery, and post-delivery. The diverse causes of motor problems perhaps reflect that much of the brain is dedicated to producing appropriate motor responses to sensory input. Some cases of cerebral palsy are associated with anomalies in the cerebrospinal tract, the communication pathway linking brain with spine. If the motor-cortex / basal ganglia / cerebellum hierarchy is not receiving the correct motor signals from the body, this can impair learning of appropriate motor plans. Paul S, Nahar A, Bhagawati M, Kunwar AJ. A Review on Recent Advances of Cerebral Palsy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022 Jul 30;2022:2622310. doi: 10.1155/2022/2622310. PMID: 35941906; PMCID: PMC9356840.; Korzeniewski SJ, Birbeck G, DeLano MC, Potchen MJ, Paneth N. A systematic review of neuroimaging for cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 2008 Feb;23(2):216-27. doi: 10.1177/0883073807307983. PMID: 18263759.

- Developmental conditions and the limbic system (though note, in most cases, subtle differences in multiple areas are observed):

- Childhood anxiety disorders and the amygdala: Blackford JU, Pine DS. Neural substrates of childhood anxiety disorders: a review of neuroimaging findings. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012 Jul;21(3):501-25. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.002. Epub 2012 Jun 4. PMID: 22800991; PMCID: PMC3489468.

- Autism, and amygdala and social function: Donovan AP, Basson MA. The neuroanatomy of autism – a developmental perspective. J Anat. 2017 Jan;230(1):4-15. doi: 10.1111/joa.12542. Epub 2016 Sep 12. PMID: 27620360; PMCID: PMC5192959.

- Callous and unemotional traits and the insula: Raschle NM, Menks WM, Fehlbaum LV, Steppan M, Smaragdi A, Gonzalez-Madruga K, Rogers J, Clanton R, Kohls G, Martinelli A, Bernhard A, Konrad K, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Freitag CM, Fairchild G, De Brito SA, Stadler C. Callous-unemotional traits and brain structure: Sex-specific effects in anterior insula of typically-developing youths. Neuroimage Clin. 2017 Dec 9;17:856-864. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.12.015. PMID: 29527490; PMCID: PMC5842751.

- Orbitofrontal cortex, limbic system, and conduct disorder: Gao Yidian, Jiang Yali, Ming Qingsen, Zhang Jibiao, Ma Ren, Wu Qiong, Dong Daifeng, Guo Xiao, Liu Mingli, Wang Xiang, Situ Weijun, Pauli Ruth, Yao Shuqiao (2020). Gray Matter Changes in the Orbitofrontal-Paralimbic Cortex in Male Youths With Non-comorbid Conduct Disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00843. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00843; Passamonti L, Fairchild G, Fornito A, Goodyer IM, Nimmo-Smith I, Hagan CC, Calder AJ. Abnormal anatomical connectivity between the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex in conduct disorder. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048789. Epub 2012 Nov 7.

- Developmental disorders and the basal ganglia (though note, in most cases, subtle differences in multiple areas are observed):

- Basal ganglia and stuttering: Chang SE, Guenther FH. Involvement of the Cortico-Basal Ganglia-Thalamocortical Loop in Developmental Stuttering. Front Psychol. 2020 Jan 28;10:3088. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03088. PMID: 32047456; PMCID: PMC6997432. Alm PA. Stuttering and the basal ganglia circuits: a critical review of possible relations. J Commun Disord. 2004 Jul-Aug;37(4):325-69. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.03.001. PMID: 15159193.

- Tourette’s syndrome, motor tics, and basal ganglia: Caligiore D, Mannella F, Arbib MA, Baldassarre G. Dysfunctions of the basal ganglia-cerebellar-thalamo-cortical system produce motor tics in Tourette syndrome. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017 Mar 30;13(3):e1005395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005395. PMID: 28358814; PMCID: PMC5373520.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder and basal ganglia, example of this work: Chen J, Tian C, Zhang Q, Xiang H, Wang R, Hu X, Zeng X. Changes in Volume of Subregions Within Basal Ganglia in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Study With Atlas-Based and VBM Methods. Front Neurosci. 2022 Jun 20;16:890616. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.890616. PMID: 35794954; PMCID: PMC9251343.

- Developmental coordination disorder and the cerebellum: Biotteau M, Chaix Y, Blais M, Tallet J, Péran P, Albaret JM. Neural Signature of DCD: A Critical Review of MRI Neuroimaging Studies. Front Neurol. 2016 Dec 16;7:227. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00227. PMID: 28018285; PMCID: PMC5159484.

- Midbrain / brainstem developmental disorders: Hans J. ten Donkelaar, Martin Lammens, Johannes R.M. Cruysberg and Cor W.J.R. Cremers (2006). Development and Developmental Disorders of the Brain Stem. In Hans J. Donkelaar, Martin Lammens, Akira Hori (Eds.) Clinical Neuroembryology: Development and Developmental Disorders of the Human Central Nervous System (p. 321-370). Springer. DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-54687-7_7. Barkovich AJ. Developmental disorders of the midbrain and hindbrain. Front Neuroanat. 2012 Mar 6;6:7. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00007. PMID: 22408608; PMCID: PMC3294267.

- ‘Environmental disruptions to early development can also affect multiple systems. For an environmental ‘sledgehammer’ event, take the example of the Romanian orphans who experienced extreme physical and social deprivation‘ – Chugani and colleagues’ fMRI study of these Romanian children subsequently showed significantly decreased activity in the orbital frontal gyrus, parts of the prefrontal cortex, the temporal cortex, the hippocampus, the amygdala and the brain stem. Chugani concluded that the dysfunction in these brain regions may have resulted from the stress of early global deprivation and be involved in the long-term cognitive and behavioural deficits displayed by some Romanian orphans: Chugani HT, Behen ME, Muzik O, Juhász C, Nagy F, Chugani DC. Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: a study of postinstitutionalized Romanian orphans. Neuroimage. 2001 Dec;14(6):1290-301. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0917. PMID: 11707085.

- ‘Differences in intelligence aren’t closely tied to differences in personality’ – for example, a small genetic correlation (overlap) is observed between factors of intelligence and psychopathology in children. That is, different genetic variation is linked to general intelligence and extreme variations of personality. Grotzinger and colleagues reported a small genetic correlation of -.19 between additive genetic variation for the general intelligence ‘g’ factor and psychopathology ‘p’ factor (negative because poor mental health impacts on IQ test score achievement), while the overlap (correlation) between environmental factors causing children to be similar and environmental factors causing children to be different were both higher, .39 and .33 respectively: Grotzinger AD, Cheung AK, Patterson MW, Harden KP, Tucker-Drob EM. Genetic and Environmental Links between : General Factors of Psychopathology and Cognitive Ability in Early Childhood. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019 May;7(3):430-444. doi: 10.1177/2167702618820018. Epub 2019 Jan 18. PMID: 31440427; PMCID: PMC6706081.

- ‘Giftedness does not arise through mutations; it’s not a mirror image to genetic syndromes. Significant mutations almost always make development worse.‘ – Significant mutations generally make things worse, but this mustn’t always be true because evolution does require significant mutations for major biological innovations. However, the useful big mutations are as rare as hen’s teeth (teeth which evolution has not yet produced, hence the idiom!).

- We’re just covering giftedness here, that is, achievements against well understood societal benchmarks which fall beyond the expertise achieved merely through extensive practice. We are not considering more mysterious skills such as creativity or ‘genius’, or how they might align with personality (such as addictive behaviour) or mental illness. We’re also not considering mastery of decision making and empathy, involved in skills such as wisdom and compassion.

- ‘[On the genetic side] giftedness is only produced by extremes of typical variation, an accumulation of many genetic variants all making brain function better‘ – Here’s a paper on the polygenic nature of giftedness: Thomas MSC. A neurocomputational model of developmental trajectories of gifted children under a polygenic model: When are gifted children held back by poor environments? Intelligence. 2018 Jul-Aug;69:200-212. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2018.06.008. PMID: 30100647; PMCID: PMC6075940.

- ‘a cortex with large computational capacity‘ – Here’s a paper on the neuroanatomy of giftedness focusing on differences in white matter connectivity in memory systems associated with high cognitive performance: Kuhn T, Blades R, Gottlieb L, Knudsen K, Ashdown C, Martin-Harris L, Ghahremani D, Dang BH, Bilder RM, Bookheimer SY. Neuroanatomical differences in the memory systems of intellectual giftedness and typical development. Brain Behav. 2021 Nov;11(11):e2348. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2348. Epub 2021 Oct 14. PMID: 34651457; PMCID: PMC8613411.

Let’s break one we made earlier

- ‘For the cortex especially, where you are is what you do. There is different content in different regions. If the adult brain then experiences damage to a specific area, this can result in quite specific loss of behaviour‘ – For more on notable cases of selective behavioural deficits following brain damage, see Code, C., Wallesch, C-W., Joanette, Y. & Roch, A. (1996) Classic Cases in Neuropsychology. Psychology Press.

- ‘Damage to Broca’s area produces a loss of the ability to produce language‘ – there is no doubt that Broca’s area, in the cortex of the left posterior inferior frontal gyrus, is involved in language production. In that sense Paul Broca’s initial observations in the 1860’s have stood the test of time, and this is a tribute to Broca’s careful behavioural and anatomical analysis of the relatively few patients he had. However, Broca did not dissect the brain of his two most famous patients (Leborgne, nicknamed ‘Tan’ after the one word he could say, and Lelong), but only described the surface damage. The brains of these two patients were fortunately preserved, and in 2007 Dronkers and colleagues used modern MRI scanning to investigate the detailed damage (Dronkers et al, Brain, 130(5), 1432-1441, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awm042). Their key finding was that damage was more extensive than Broca concluded, involving subcortical areas such as the basal ganglia and insula, and the arcuate fasciculus (the major pathway connecting Wernicke’s area in the temporal lobe with Broca’s area in the frontal lobe). Dronker and colleagues were happy to conclude that Broca’s area is involved in speech production, but there is still a debate on the additional contribution of subcortical systems. For more, see the section on language in Chapter 9.

- ‘But if you damage this high-up spatial region in the parietal cortex, you get something called neglect‘ – here’s a review of the phenomenon of spatial neglect: Adair JC, Barrett AM. Spatial neglect: clinical and neuroscience review: a wealth of information on the poverty of spatial attention. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008 Oct;1142:21-43. doi: 10.1196/annals.1444.008. And a recent assessment of its prevalence, concluding it is generally caused by right hemisphere damage, but sometimes by left hemisphere damage too: Esposito E, Shekhtman G, Chen P. Prevalence of spatial neglect post-stroke: A systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2021 Sep;64(5):101459. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.10.010. Epub 2021 Sep 24. PMID: 33246185.

- ‘One of the most influential studies in neuroscience was one of the earliest. In 1848, Phineas Gage…‘ – the case of Phineas Gage has generated discussion from the time of his accident (1848) to the present day. Although observations of his recovery and behavioural problems post-accident were rather fragmented and unsystematic, there was enough detail to argue about…..at the time there was a lively debate on the nature of cerebral function. On one side were the cerebral localisationists (they probably didn’t call themselves that), who thought that particular functions were strictly localised to specific areas of the cortex. At the extreme of this approach were the phrenologists, such as Gall, who argued that different aspects of personality were located in different parts of the brain and would produce correlated ‘bumps’ on the skull that could be interpreted by a skilled phrenologist. Although the skull bumps/personality link was rapidly debunked, the idea of localised functions in the brain remained popular, and contrasted with the ‘equipotentiality’ hypothesis that the cortex in particular was a generalist, with specific functions distributed across large areas rather than being localised. Gage had lost large chunks of his left frontal lobe. Localisationists emphasised the behavioural problems he had – social skills, loss of behavioural control etc, which must be centered in the damaged areas, while generalists emphasised the impressive recovery he made, e.g. being able to hold down a job i.e. no specific functions were lost. The debate continued into the 20th century, particularly in the work of Karl Lashley (e.g. Lashley, K.S., Brain Mechanisms and Intelligence, University of Chicago Press, 1929). He proposed the Law of Mass Action, whereby it was the amount of cortex damaged rather than its precise location that resulted in behavioural impairments. The debate then ran for several more decades, but with the recent and rapid introduction of advanced neuroscience methods we can now see that pretty well everyone was right – to some extent.

- Some cortical functions are clearly localised (remember, where you are is what you do). Primary sensory areas such as visual, auditory or somatosensory cortex have specific and characteristic functions that are predictably affected by damage. Frontal areas support executive functions, planning, memory, decision making, integrating the activity of multiple brain systems. A general ‘localisation’ is possible (see our Battenberg model of prefrontal cortex, p.90), but the behavioural categories are by their very nature too complex to be neatly localised along the lines of sensory cortex. Phineas Gage initially lost functions through frontal lobe damage, but the brain’s capacity for plasticity and reorganisation then compensated (see Macmillan, M, 2002, An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage. MIT Press, for a thorough analysis of the Gage saga). For more, see also: Damasio, H., Grabowski, T., Frank, R., Galaburda, A. M., & Damasio, A. R. (1994). The return of Phineas Gage: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. Science, 264(5162), 1102-1105. Van Horn, J.D., Irimia, A., Torgerson, C.M., Chambers, M.C., Kikinis, R. Toga, A.W. (2012) Mapping connectivity damage in the case of Phineas Gage. PloSone, 7(5), e37454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037454

- ‘For example, one patient, HM, had both left and right hippocampi removed for [due to intractible epilespsy]. The result was a particular deficit in episodic memory‘ – Henry Molaison (HM) probably contributed more to psychology than most actual psychologists. From his operation in 1953 (bilateral removal of large parts of his temporal lobe to relieve his severe epileptic condition) he has been studied by psychologists, up to his death in 2008. As our book outlines, his amnesic syndrome pointed to the role of the hippocampus in the transfer from short-term memory to long-term memory and the separation of episodic memory from procedural memory, major contributions to later models of memory and the brain. The subject of literally hundreds of research projects (with his episodic amnesia, he was happy to be tested over and over again), HM is the most famous case in neuropsychology (Squire, L.R. (2009) The legacy of patient H.M. for neuroscience. Neuron, 61, 6-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.023). Incidentally, his bilateral temporal lobectomy also involved bilateral removal of the amygdala, something that is rarely commented upon… though see Hebben et al, 1985, Diminished ability to interpret and report internal states after bilateral medial temporal resection: Case H.M. Behavioral Neuroscience, 99, 1031-1039. Hebben and colleagues link HM’s decreased sensitivity to pain and lack of fear responses (other emotions appeared in the normal range) to the loss of the amygdala. For more on HM, see Corkin, S. (2014) Permanent present tense: The man with no memory, and what he taught the world. Penguin Books.

- ‘sometimes damage produces unexpected effects, such as alien hand syndrome‘ – For more on alien hand syndrome: see Aboitiz, F.; Carrasco, X.; Schröter, C.; Zaidel, D.; Zaidel, E.; Lavados, M. (2003). The alien hand syndrome: classification of forms reported and discussion of a new condition. Neurological Sciences. 24 (4): 252–257. doi:10.1007/s10072-003-0149-4. ISSN 1590-1874. PMID 14658042. S2CID 24643561

- ‘the lowest part of the cortical motor hierarchy that controls hand movement, the primary motor area, starts to operate in isolation of the level above it which normally generates the plan‘ – Normal order of processing in the motor system: Kayser, A. S.; Sun, F. T.; D’esposito, M. (2009). A comparison of Granger causality and coherency in fMRI-based analysis of the motor system. Human Brain Mapping. 30 (11): 3475–3494. doi:10.1002/hbm.20771. PMC 2767459. PMID 19387980

- ‘When a person insists that a loved one has been replaced by an imposter, called Capgras delusion, this is a disconnection...’ – Explanation of Capgras delusion as disconnection of face recognition and emotional response: Hirstein, W (2010). The misidentification syndromes as mindreading disorders. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 15 (1): 233–60. doi:10.1080/13546800903414891. PMID 20017039. S2CID 7811360.

- ‘Those computations end up spitting out a delusional belief‘ – Discussion of how disconnection then leads to a delusional belief: Davies, M.; Coltheart, M.; Langdon, R.; Breen, N. (2001). Monothematic delusions: Towards a two-factor account. Philosophy, Psychiatry, and Psychology. 8 (2): 133–158. doi:10.1353/ppp.2001.0007. S2CID 43914021. Caveat: not all cases of damage and not all sets of symptoms are the same.

- ‘Damage does reveal one interesting fact about how brains differ when they are working normally‘ – The example showing five sufficient but not necessary brain areas to do the semantic classification task, where damage reveals different peolle must be using different subsets to normally perform the task, is unpublished work from Cathy Price’s lab, which she has presented at seminars. She gave us the following references as showing the main principles behind the finding, in published papers: Seghier ML, Lee HL, Schofield T, Ellis CL, Price CJ. (2008). Inter-subject variability in the use of two different neuronal networks for reading aloud familiar words. Neuroimage. 2008 Sep 1;42(3):1226-36. Richardson FM, Seghier ML, Leff AP, Thomas MSC, Price CJ. (2011). Multiple routes from occipital to temporal cortices during reading. J Neurosci. 2011 Jun 1;31(22):8239-47. Seghier ML, Bagdasaryan J, Jung DE, Price CJ. (2014). The importance of premotor cortex for supporting speech production after left capsular-putaminal damage. J Neurosci. 2014 Oct 22;34(43):14338-48. Kherif F, Josse G, Seghier ML, Price CJ. (2009). The main sources of intersubject variability in neuronal activation for reading aloud. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009 Apr;21(4):654-68.

- ‘Damage has different effects when it happens in the developing brain, which is still in the process of self-organising its functional circuits‘ – Early plasticity / vulnerability of the child’s brain, for an overview, see: Thomas, M. S. C. (2003). Essay Review: Limits on plasticity. Journal of Cognition and Development, 4:1, 99-125, DOI: 10.1080/15248372.2003.9669684.

- ‘if the same left-hemisphere areas which cause Broca’s or Wernicke’s aphasia in an adult are damaged in a young child… he or she usually recovers to exhibit language skills in the normal range‘ – Early focal brain damage and child language development: Bates, E., & Roe, K. (2001). Language development in children with unilateral brain injury. In C. A. Nelson & M. Luciana (Eds.), Handbook of developmental cognitive neuroscience (pp. 281–307). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Disrupting the dynamics

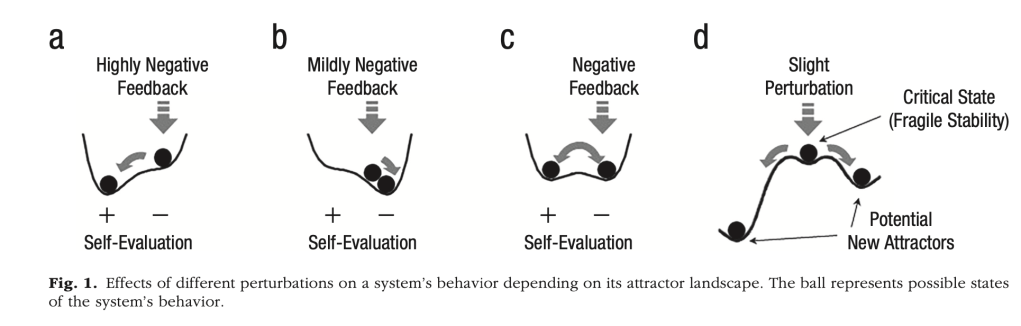

- In this section, we initially had an idea that we were going to introduce psychiatric conditions using a metaphor that focused on dynamics. We would start by thinking about the iterative loops that experience follows: motivations alter control of behaviour which yields experiences which produce rewards, memories, and emotional responses, which affect motivations, which alter control of behaviour which yields experiences which… and so on. We were going to introduce a metaphor to convey the idea of attractor states in the dynamics of these interactions, like a rubber ball bouncing across the floor. An ‘attractor’ is a state of a system which it readily falls into to (and can potentially get stuck in). And then we’d say that if the system is detuned in different ways, by changes in activity or connectivity, the system can get stuck in certain states (beliefs, behaviours), or fall too easily into and fail to exit certain states (depression), or be too ready to leave certain states (anxiety, distractibility). Balls can be too bouncy or not bouncy enough (internal factors), the floor too hard or too soft (experiences and the environment), both altering the typical way a ball bounces. That was the metaphor anyway.

- Well, then we’d discuss schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, psychosis in these terms. We’d talk about neurotransmitters as possible mechanisms of this detuning, and how the actions of certain drugs made us think that this interpretation might be true. Schizophrenia might be caused in part by detuning of the modulatory system’s control over and monitoring of posterior cortex (perhaps we’d link back to alien hand syndrome or Capgras syndrome, where disruptions to internal states, of prediction or control, lead to delusional beliefs). We’d link back to nature/nurture, to argue the disruption to dynamics could be caused by intrinsic differences in internal dynamics (not the right amount of neurotransmitters like serotonin, norepinephrine or dopamine) so that events are not rewarding enough or there is insufficient generation of proactive behaviour; or by external events (a lot of bad things happening causes you to become depressed); or by a combination of both internal and external factors (a system with non-optimal tuning is more likely to be pushed into poor dynamics by some bad life events). Perhaps we’d throw in the finding that sometimes the drugs stop working: perhaps when you dose up on extra neurotransmitters, the brain eventually adjusts to counteract the increase, using homeostatic mechanisms designed to maintain the biochemical status quo; or perhaps because if the cause of the unusual dynamics is bad things in the world, putting a plaster on the internal dynamics won’t have made those events go away and the pressure on the dynamics will persist. Sometimes the world is indeed a mad, bad place. To finish with, perhaps we would have pointed out that this dynamical system can also be ‘fried’ by super strong environmental events, such as threat to life: extreme experiences can burn-in changes to the amygdala (sensitivity to threat), the hippocampus (memory of episodes) or medial prefrontal cortex (fear regulation) that cause lasting effects on future behaviour, as in post-traumatic stress disorder. Perhaps there are good versions of super strong environmental events, too, such as when you win the lottery or a reality TV competition, which also fry future self-regulation and judgement…

- Ah, but in the end, we didn’t think we could make the metaphor fly, so we include it here just for fun. But if you’re interested in dynamical systems – ones that exhibit internal states which evolve over time and interact with externally applied input – then this book gives a good introduction to dynamical systems theory in the context of neurocomputation and development: Spencer, J., Thomas, M. S. C., & McClelland, J. L. (2009). Toward a new unified theory of development: Connectionism and dynamical systems theory re-considered. Oxford: Oxford University Press. And if you’re interested in a dynamical systems perspective on psychiatric disorders, here’s an illustrative paper that focuses on depression within this framework: Cramer AOJ, van Borkulo CD, Giltay EJ, van der Maas HLJ, Kendler KS, Scheffer M, et al. (2016) Major Depression as a Complex Dynamic System. PLoS ONE 11(12): e0167490. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167490. And if you interested in how you can characterise the normal functioning of the cognitive system in terms of attractor states, see: Gernigon, C., Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Vallacher, R. R., & van Geert, P. L. C. (2023). How the Complexity of Psychological Processes Reframes the Issue of Reproducibility in Psychological Science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231187324. Figure 1 gives a flavour of those attractors, in this case showing how an individual’s self-evaluation may be influenced by feedback. Different systems have different dynamics and attractor ‘landscapes’, so that externally dlivered feedback produces different responses:

- ‘Psychiatry is embedded in medical science, as psychiatrists complete a medical degree before specialising‘ – As we see in the text, the psychiatric/medical model of mental disorders dominates the diagnosis and treatment of conditions such as schizophrenia, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and autism. Over the years the DSM system of diagnosis and classification has had to be flexible, as social and cultural changes influence our awareness of and attitudes e.g. to homosexuality. Other categories of disorder e.g. eating disorders, addictive disorders, have been recognised and introduced more recently (a large and unanswered question is whether such ‘disorders’ have always been around and simply undiagnosed). For the current diagnostic manual, see: American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition). https://doi-org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- The DSM/medical approach has always been subject to criticism. It pathologises behaviour, although with the best of intentions. Modelled on medical conditions, it tries to outline a ‘nosology’ for a disorder – this means that in an ideal world the diagnosis has certain outcomes – cause, treatment, and outcome. For medical conditions such as cancer or a broken leg, this can work reasonably well, but for psychological disorders it is less satisfactory. For schizophrenia, for instance, we do not know the causes and outcomes are unpredictable (drugs are only effective for 40-50% of patients). In the 1960s the anti-psychiatry movement developed as a reaction against medical psychiatry. Szasz (2011; first published 1979) was a leader of this movement, arguing that psychological problems were embedded in problems of living (Szasz, T. (2011) The myth of mental illness: 50 years later. The Psychiatrist, 35, 179-182. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.110.031310). The psychiatric approach ignored the personal and emotional aspects of behavioural problems, but was used instead to drug and in many cases institutionalise ‘difficult’ patients. (See the film ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ for strong arguments against the psychiatric approach). The anti-psychiatry approach advocated non-drug talking therapies based in psychoanalysis and existential psychology (another leader of the movement was R.D. Laing – see ‘The Divided Self’, Penguin, 1960).

Schizophrenia

- ‘Even today, two people diagnosed with schizophrenia may have no symptoms in common‘ – There is no doubt that there are major issues with psychiatry. We saw that two people diagnosed with schizophrenia may have no symptoms in common; that there is a major issue with positive versus negative symptoms (see the British Journal of Psychiatry, 2023, vol.223, special issue no. 1, ‘Negative symptoms of schizophrenia’, for an exhaustive review of research into negative symptoms), and despite three generations of antipsychotic drugs, outcome for 50% of patients is still poor. However, many people with schizophrenia or depression do benefit from drugs, and the DSM system is certainly useful for standardising diagnostic criteria so that we know what we are talking about.

- A softer position, but still critical of current psychiatric approaches, is taken by Richard Bentall (Bentall, R., Madness Explained: Psychosis and Human Nature; Penguin, 2003). One important practical point he makes is the symptom overlap between schizophrenia and e.g. bipolar disorder. Given that most problems in schizophrenia research emerge from its varied, heterogenous symptoms, Bentall suggests that we should focus instead on the phenomenology and neurobiology of individual symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions, regardless of the syndrome label. This should also include the individual experience and meaning of the symptom i.e. a multi-level analysis, from experience to neuron. In practice, this is already happening within neuroscience research, as we see later.

Explanations – neurotransmitters

- ‘Antipsychotic drugs were introduced in the early 1950s, and one, chlorpromazine, was found to be reasonably effective in around 50% of patients with schizophrenia… it turned out that all drugs effective against schizophrenia were potent antagonists at dopamine receptors‘ – There have been thousands of papers published on dopamine (DA) and schizophrenia, and only slightly less on the potential involvement of other neurotransmitters, peptides and proteins. The review by Stepnicki et al (2018) is exhaustive and detailed – you may need to complete your Masters in Neuropharmacology before understanding all of it (Stepnicki, P, Kondej, M. & Kaczor, A.A. (2018) Current concepts and treatments of schizophrenia. Molecules, 23, 2087-2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23082087). However, skim read for the key points – issues with drug treatment, problems with the dopamine explanation, potential new targets for drug therapies etc. The idea that positive symptoms represent subcortical DA hyperactivity – too much – and that cortical DA hypoactivity – too little – is linked to negative symptoms respectively is still accepted. The first antipsychotic, chlorpromazine (CPZ; trade name, largactyl) was introduced in the early 1950s, by trial and error. It has always been a feature of neuropsychopharmacology that new compounds are routinely assessed across a range of disorders just to see if they work; things are a little more systematic now – Stepnicki et al discuss the potential role of beta-arrestin, a small protein active at glutamate receptors; glutamate had been implicated in regulating cortical DA activity and in schizophrenia, so let’s develop beta arrestin antagonists and see if they are clinically active… Consistent results are not yet in…

- How did they stumble across chlorpromazine in the 1950s? CPZ was being used in hospitals as a pre-operative sedative in surgery patients when a psychiatrist working next door thought he would try it on his patients with schizophrenia, and found a significant therapeutic benefit (especially compared with the frontal lobotomy, then widely used in treating schizophrenia). So began the age of drug therapy for schizophrenia (for more on the story of chlorpromazine, see Lopez-Munoz, F. et al, 2004, Half a century since the introduction of chlorpromazine and the birth of modern psychopharmacology; Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 28, 205-208; https://10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00165-9).

- Where are we now? Stepnicki et al (2018) bring us pretty well up to date, with a review of potential targets for new drugs – e.g. glutamate, serotonin, acetylcholine, GABA and the endocannabinoid system (the brain network targeted by the active ingredients in cannabis). There are, nevertheless, practical problems in testing new drugs. Clinical trials need to use large numbers of participants, all of whom should have the same profile of symptoms (e.g. mainly positive or mainly negative symptoms). Ideally they should also be drug-naïve (i.e. first episode patients), with similar socioeconomic backgrounds (age, gender, cultural background etc). These conditions are often impossible to fulfil, so compromises are made e.g. adding new drugs to current medication, or using patients with a mix of symptoms.

- One of the more promising avenues is the glutamate hypothesis. Uno & Coyle (2019) review the status of this approach (Uono, Y. & Goyle, J.T. (2019) Glutamate hypothesis in schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 73(5), 204-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/pcn.12823). There is some evidence for glutamate abnormalities in schizophrenia (glutamate is the most common excitatory transmitter in the brain, which interacts with and regulates many other neurotransmitters). And some drugs that induce psychotic states, such as ketamine, seem to act through glutamate receptors (also known as NMDA receptors. Don’t worry abut the acronym…). However, there is little clinical evidence so far for glutamate-active drugs being effective antipsychotics.

- McCutcheon et al (2020) review support for both glutamate and dopamine (and their interaction) involvement in schizophrenia (McCutcheon, R., Krystal, J.H. & Howes, O.D. (2020) Dopamine and glutamate in schizophrenia: Biology, symptoms, and treatment. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 227-235. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20440). This is another dense paper, but the general messages are clear. A number of changes to these systems are found in schizophrenia, but their interactions are complex and widespread throughout the brain. The authors also review genetic factors, concluding that some of the genes implicated in schizophrenia are linked to glutamate function (therefore a significant genetic loading), but matching genetic factors are not found for dopamine. Therefore dopamine abnormalities are more likely to related to non-genetic factors such as early stress (this is picked up in the McCutcheon et al, 2023 paper). They also emphasise that the widespread nature of glutamate makes it difficult to design drugs that act on those networks relevant to schizophrenia.

- Before moving on, a quick reminder of the complexity of this area (Stepnicki et al, 2018). At the behavioural level we have the heterogeneity (‘variability’) of the symptoms of schizophrenia. Symptoms cover cognitive, affective (emotion), and motivational aspects of behaviour. These will involve multiple neurotransmitter systems, including both long axon pathways (dopamine, serotonin etc) and short axon interneuron networks utilising e.g. GABA and glutamate. Drugs targeting any of these could in theory influence the course and outcome of schizophrenia.

- Here are some other good sources for recent research on schizophrenia and neurotransmitters: Roelfs, D., Alnaes, D. & 6 others (2021) Phenotypically independent profiles relevant to mental health are genetically correlated. Translational Psychiatry, 11, 202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01313-x; Taylor, M.J., Freeman, D., Lundstrom, S., Larsson, H. & Ronald, A. (2022) Heritability of psychotic experiences in adolescents and interaction with environmental risk. JAMA Psychiatry, published online: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1947

Explanations – genetics, neuropathology, and neurodevelopment

- ‘It has been known for 60 years that schizophrenia has a high genetic loading… the closer the genetic relationship to someone with schizophrenia the greater the chance of developing the disorder‘ – While remembering that the various explanatory approaches to schizophrenia are not mutually exclusive, there are distinct research areas. In the 1950s and 1960s twin studies (comparing the incidence of schizophrenia in genetically-identical monozygotic twins with non-identical dizygotic twins), as well as family and adoption studies had established a genetic influence in schizophrenia. Current estimates put it at about 70% (Rees, E., O’Donovan, M.C., & Owen, M.J. (2015) Genetics of schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 2, 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2014.07.001). There were early attempts to link schizophrenia to a single ‘big bang’ ‘schizophrenia’ gene, but the rapid advances in methods of gene analysis over the last 25 years soon showed this was unrealistic. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in particular have produced a wealth of findings (Rees et al., 2015), though not much clarity.

- Over 100 genetic factors have been identified (though different studies tend to come up with different profiles, albeit with some findings in common), but these cover a range of genetic changes. There may be de novo (‘brand new’) mutations to single genes, copy number variants (CNVs; repeated copies of a segment of the genome), and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; these are changes to single letters of the DNA code, e.g. substitution of the nucleotide guanine for thymine at one particular point in the genome). CNVs and SNPs may affect gene sections or non-coding sections of the genome; most of the genome is non-coding (i.e. not part of a gene that produces a protein) but it is vital in the regulation of gene expression, turning genes on or off at the appropriate time.

- These changes tend to be elevated in schizophrenia (Rees et al., 2015), and some have been associated with genetic control of synaptic plasticity, receptor activity, neural growth and development, and the immune system. Some studies show immune system dysfunction and neuroinflammation in around 30% of people with schizophrenia, and propose an important role for immune dysfunction in the disorder – see Ermakov, E. et al, Immune system abnormalities in schizophrenia: an integrative view and translational perspectives. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 880568; https//doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.880568. For example, the immune system usually be utilised in synaptic pruning; an over-active immune system may therefore disrupt neural connectivity.

- Unfortunately, there is lack of consistency in basic findings, and we still know too little about the pathways between variation at the genetic level and e.g. brain systems and their development (though progress is impressively rapid. See this space in two years time…). We do know that there is a significant genetic loading in schizophrenia, and also that there is an overlap between the genetic background to schizophrenia and other conditions such as ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), bipolar disorder, and depression. In fact, Jutla et al. (2020) propose a closer relationship between ADHD, ASD, and schizophrenia. Looking at high risk individuals (those with a family history of schizophrenia) they conclude that childhood signs of ADHD and ASD (issues with social communication, problems with attention, repetitive behaviours) are an early indication of vulnerability to later psychosis (Jutla, A., Califano, A. & 9 others (2020) Neurodevelopmental predictors of conversion to schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in adolescence and young adulthood in clinical high-risk individuals. Schizophrenia Research, 224, 170-172. https://doi.org/j.schres.2020.10.008)

- ‘If schizophrenia is not entirely determined by genetics, what are the contributing environmental factors?‘ – As explained in the ‘Nature or Nurture’ section of the book (p.168 et seq), all behaviours involve genetic-environment interactions. With schizophrenia, many environmental risk factors have been identified (Stilo & Murray, 2019; Howes & Murray, 2014; McCutcheon et al., 2023), such as birth trauma, childhood adversity (stress), lower socio-economic status (poverty), living in the city, use of cannabis, being a member of an ethnic minority and Spring birth. Each can increase the risk of schizophrenia by a small but significant percentage, but nothing like the impact of genetic vulnerability. Children who go on to develop schizophrenia as adults can show early ‘soft’ neurological signs (i.e. slight perturbations in behaviour or cognition; reviewed in McCutcheon et al, 2023), suggesting that schizophrenia may be a neurodevelopmental disorder based in complex interactions between genetic vulnerability and early environmental factors.

- References: Stilo, S.A. & Murray, R.M. (2019) Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21, Article 100. https://10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3; Howes, O.D. & Murray, R.M. (2014) Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. Lancet, 383, 1677-1687. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62036-x; McCutcheon, R.A., Keefe, R.S.E. & McGuire, P.K. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Mol Psychiatry 28, 1902–1918 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-01949-9.

- Although moving somewhat beyond the available data, Murray’s group (Stilo & Murray, 2019; Howes & Murray, 2014) have provided a speculative model of how genetics and the environment may interact in producing schizophrenia. A genetic vulnerability combines with e.g. early brain trauma and childhood adversity to sensitise the dopamine system, leading to increased dopamine synthesis and presynaptic release. Social stress during early childhood then produces negative cognitive schema (‘the world is a dangerous place’ – see section on depression for more on schema), leading to the paranoid interpretation of life experiences. This is underpinned by the dysfunctional dopamine system, which has a leading role in evaluating the salience of external stimuli. Cognitive interpretation and the search for explanations of these anomalous experiences leads to the psychotic symptoms associated with schizophrenia.

- The authors quote some evidence that stress in monkeys and humans increases dopamine synthesis and release, and the model overall has some plausibility. However it lacks detail (largely because the research evidence is not available) but is in line with the contemporary view that schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental disorder reflecting both genetic elements and non-genetic environmental factors.

- References: Delisi, L.E., Szulc, K.U., Bertisch, H.C., Majcher, M. & Brown, K. (2006) Understanding structural brain changes in schizophrenia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 8, 71-78; Kirkbride, J.B., Hameed, Y. & 15 others (2017) Ethnic minority status, age-at-immigration and psychosis risk in rural environments: Evidence form the SEPEA study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(6), 1251-1261. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx010

Schizophrenia – cognitive processing

- ‘People with schizophrenia show a range of cognitive deficits, so much so that cognitive impairment has been proposed as a potential diagnostic criterion for the disorder‘ – Cognitive impairments are not a part of the formal DSM diagnosis of schizophrenia, but they are widely present in patients. It is also likely that they underpin many of the positive and negative symptoms, as we shall see. Research (see McCutcheon et al., 2023, for a comprehensive review) has demonstrated problems with processing speed, learning, attention, working memory, language processes and theory of mind. In fact the impairments are so widespread it is hard to imagine a coherent single hypothesis to account for them, but of course it hasn’t stopped people trying.

- In fact, if we view the brain as sets of interacting systems (as this book does) – modulatory, content-specific hierarchical sensory and motor, action selection, memory, language etc – then it looks impossible to even suggest a single central dysfunction. But if we had to guess, then we would focus on the modulatory guidance and integrating systems of the prefrontal cortex.

- This is the approach of McCutcheon et al (2023), who focus on the balance between excitation and inhibition in prefrontal cortex. This is the area modulating, amongst other things, attention, working memory, and other executive functions. As pointed out in the book (p. 185), schizophrenia has been linked to dopamine hypofunction in the cortex. However, cortical microcircuits involve a range of neurotransmitters besides dopamine contributing to the balance between excitation and inhibition; long-axon excitatory neurotransmitters such as dopamine and acetylcholine, and short-axon interneurons utilising glutamate (excitatory), GABA (inhibitory) and glycine (inhibitory). McCutcheon et al propose that in schizophrenia a combination of cortical glutamate overactivity and underactivity in GABA interneurons leads to a state of cortical disinhibition, disrupting key cortical functions. These would include those executive/modulatory functions mentioned earlier, and these would lead to the cognitive impairments associated with the disorder.

- There is some evidence for the cortical alterations in neurotransmitter activity, and, as McCutcheon et al (2020) point out, these are potential targets for drug therapy aimed at the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Unfortunately, therapy targeted at just the cortex is currently impossible given the widespread brain distribution of e.g. glutamate and GABA, and the few clinical trials of e.g. cholinergic and glutamatergic compounds, have been disappointing.

- There are less detailed but broader models of the neuropsychology of schizophrenia. In 1992 Chris Frith produced ‘The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Schizophrenia’ (Psychology Press), in which he put forward some influential ideas about the symptoms of schizophrenia. One was that we needed a central monitor to decide which actions, ideas and experiences were internally generated and controlled, and which were due to some external agency (we covered some related ideas in the book, such as the dysfunctions in alien hand and Capgras syndrome). Another was that many of the symptoms of schizophrenia, positive and negative, were caused by failures of ‘metarepresentation’ – this is the process of having insight into our intentions and actions, and into the intentions and actions of others. Although research evidence at the time was not really adequate to confirm these ideas, they have been influential, and similar models have been put forward over the years. One example is the focus of Waters et al (2012) on auditory hallucinations (Waters, F., Allen, P. & 10 others (2012) Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia and non-schizophrenia populations: A review and integrated model of cognitive mechanisms. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(4), 683-692. https://10.1093/schbul.sbs045).

- Here are some more relevant papers: Wood, L., Williams, C., Billings, J., & Johnson, S.(2020) A systematic review and meta-analysis of cognitive behavioural informed psychological interventions for psychiatric patients with psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 222, 133-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.041

- Hu, M-L., Zong, X-F. & 7 others (2017) A review of the functional and anatomical default mode network in schizophrenia. Neuroscience Bulletin, 33(1), 73-84. https://10.1007/s12264-016-0090-1

- Moseley, P., Fernyhough, C. & Ellison, A. (2013) Auditory verbal hallucinations as atypical inner speech monitoring, and the potential of neurostimulation as a treatment option. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(10), 2794-2805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.10.001

- Ho, K.K.Y., Lui, S.S.Y., Hung, K.S.Y., Wang, Y., Li, Z., Cheung, E.F.C. & Chan, R.C.K. (2015) Theory of mind impairments in patients with first-episode schizophrenia and their unaffected siblings. Schizophrenia Research, 166, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.033

Major depressive disorder (MDD)