Much of the book so far has focused on how brains work in a similar way across most vertebrates, mammals, and social primates. In this chapter, we focus on things that humans do that make them special. Hooray! We are unique in … messing up the environment. No wait, save that till the next chapter. In this chapter, we’re upbeat. We cover things like language and culture, the way we fashion our environments and dream of better futures; the way we make ourselves cleverer through education; how humans construct special social hierarchies … and how we give each other awards (and the Oscar goes to). We even consider how the human brain gets to generate consciousness.

Intro

- ‘And we did say at the outset that we weren’t going to obsess about what makes humans fantastic and better as a species‘ – See who wins the my-brain-is-specialer-than-yours competition: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_animals_by_number_of_neurons

- ‘we probably have the same number of neurons as our ancestors in the wider archaic homo family tree, including Neanderthals‘ – The wider archaic homo family tree: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaic_humans

- ‘Let’s start with a couple of easy wins. Language. Undoubtedly, the ability to share ideas through language is our species’ signature cognitive skill‘ – Some introductory colour that didn’t make the final cut: To the psychologist, language is an extremely clever box of trick, a type of communication that sets humans apart in its use of syntax, a recipe for recombining a limited set of words into an infinite set of sentences, making humans immensely expressive (well, some of them). To the linguist, the world’s languages offer rich sets of grammatical rules and regulations, bylaws and practices, speech systems and vocabulary items, which can be captured in abstract systems. It’s a prized cultural artefact (the complete works of Shakespeare! Download them now); there’s a department of linguistics in every university (or should be); it’s the subject of strong normative pressures (how dare they add an apostrophe to it’s or, um, its, when your using the third person neutral possessive, I’m mean when you’re using the… boy this is tricky); and it’s a marker of social group (British audiences will know it’s so common to drop yer aitches, ain’t it – see Pygmalion for further details: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pygmalion_(play)).

Language in the brain

- ‘Language is a truly beautiful artefact, capable of infinite expression, the medium of some of our greatest works of art. And some poems.’ – Our brilliant proofreader added a note to this sentence that read “Is the sarcasm necessary?!” We agree, we’re not sure sarcasm is ever necessary! But rest assured, we are poetry lovers, too. We are partial to a bit of Rainer Maria Rilke. As Rainer asked, ‘Do you remember still the falling stars / that like swift horses through the heavens raced / and suddenly leaped across the hurdles / of our wishes—do you recall?’ Hippocampus, right there.

- ‘Now let’s get into the nitty gritty of how language works in the brain‘ – The nitty gritty account of how language works in the brain is largely based on: Price CJ. A review and synthesis of the first 20 years of PET and fMRI studies of heard speech, spoken language and reading. Neuroimage. 2012 Aug 15;62(2):816-47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.062.

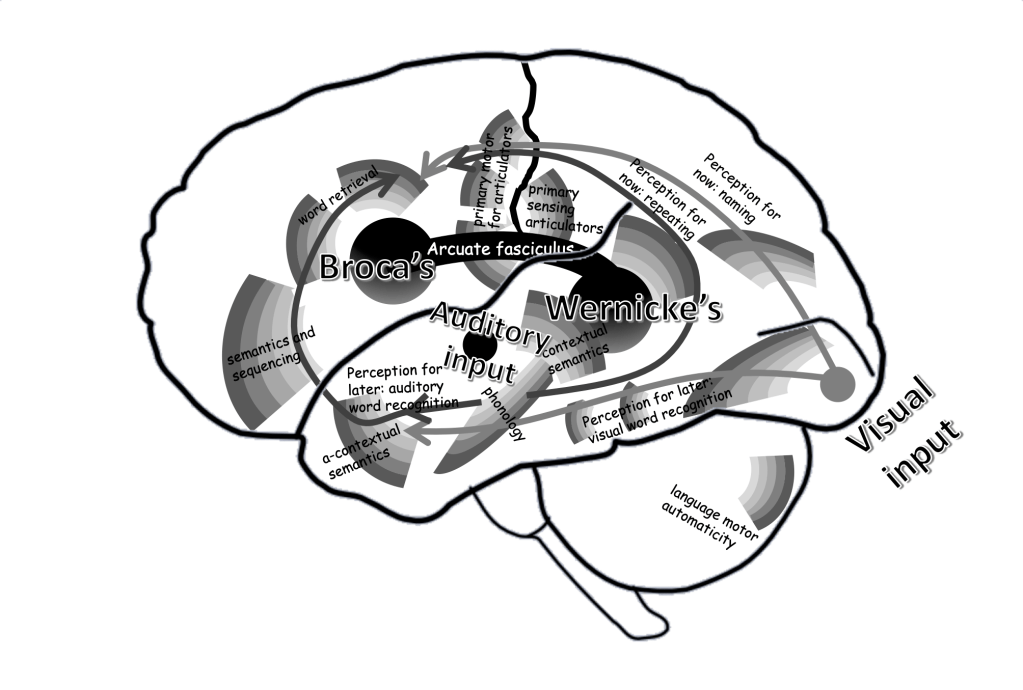

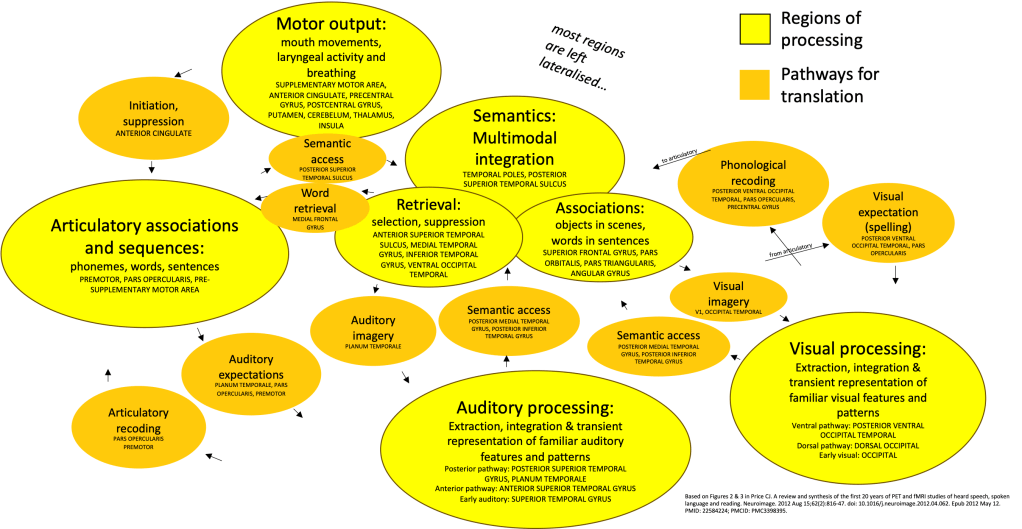

- Here’s our best schematic of the language brain based on Price’s (2012) synthesis, but it wasn’t pretty enough, or indeed comprehensible enough, to make it into the book. The ‘grey rainbows’ represent sensory or motor hierarchies, the schematic shows the two routes from perception to action (separately for oral and written modalities), the mechanisms for sequencing and retrieval, and the two semantic stores, contextual and a-contextual, as well as Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas as linked hubs.

- Ug, right? We had another go, using our favourite ‘bubbles’ format, but still we found we had to include pathways as well as systems, because language is mostly about translating: from auditory information to phonological information and from phonological information to meaning (comprehension); and from meaning to phonological information and to articulatory sequences (production) … and that’s before you learn to read and try to map it all onto visual symbols. Let alone try to spell words like ‘acquiescence’.

- ‘First, there’s the perception-for-now dorsal route, allowing repetition of the speech without accessing meaning … The perception-for-later route by contrast involves connecting the sounds of words with two different stores of meaning‘ – Ventral and dorsal routes for language: Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, Kümmerer D, Kellmeyer P, Vry MS, Umarova R, Musso M, Glauche V, Abel S, Huber W, Rijntjes M, Hennig J, Weiller C. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Nov 18;105(46):18035-40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805234105.

- ‘two different stores of meaning, which work in partnership. One store … [is a hub that] recognises objects irrespective of the sensory context in which they are encountered. The other store of meaning … processes meaning in context, the actual emerging understanding as you process the words in a sentence‘ – For the view of the roles of the two semantic stores in anterior temporal lobe and posterior superior temporal regions (here discussed in terms of another name for the region, the angular gyrus), see: Kuhnke P, Chapman CA, Cheung VKM, Turker S, Graessner A, Martin S, Williams KA, Hartwigsen G. The role of the angular gyrus in semantic cognition: a synthesis of five functional neuroimaging studies. Brain Struct Funct. 2023 Jan;228(1):273-291. doi: 10.1007/s00429-022-02493-y.

- There are other interpretations of the respective roles of these two stores, e.g., that anterior temporal lobe (ATL) is an amodal hub while the angular gyrus is a multi-model hub, that is, it is still couching information in sensory information; or that the ATL is more taxonomic and abstract while the angular gyrus is more concrete, thematic and associative. We follow Price (2012) in viewing Wernicke’s area as about contextual integration of meaning.

- ‘you can still pass 20-questions type tests about word meanings using the context-independent store of definitions at the front of the temporal lobe‘ – Semantic categorisations are still possible in adults with Wernicke’s aphasia, see: Robson H, Zahn R, Keidel JL, Binney RJ, Sage K, Lambon Ralph MA. The anterior temporal lobes support residual comprehension in Wernicke’s aphasia. Brain. 2014 Mar;137(Pt 3):931-43. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt373. See Jeffries and Lambon Ralph for a comparison between patients with Wernicke’s aphasia and patients who have semantic dementia, which tends to initially impact the anterior temporal lobe and impact knowledge of meanings across modalities, that is, differential damage to the two semantic stores: Jefferies E, Lambon Ralph MA. Semantic impairment in stroke aphasia versus semantic dementia: a case-series comparison. Brain. 2006 Aug;129(Pt 8):2132-47. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl153.

- ‘the brain makes predictions of what motor commands should produce what sounds‘ – Learning phonology by predicting the sensory consequences of motor outputs – here’s a neurocomputational model that explored this account: Plaut, D. C. and Kello, C. T. (1999). The emergence of phonology from the interplay of speech comprehension and production: A distributed connectionist approach. In B. MacWhinney (Ed.), The emergence of language (pp. 381-415). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

The special bit

- ‘it’s hard to find any part of the brain’s language system that just processes syntax and not a word’s meaning‘ – See: Fedorenko E, Blank IA, Siegelman M, Mineroff Z. Lack of selectivity for syntax relative to word meanings throughout the language network. Cognition. 2020 Oct;203:104348. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104348.

- ‘arithmetic, music, and action observation/planning, these skills don’t employ the same regions within Broca’s area‘ – For evidence that regions of Broca’s area are specific to language sequences and not arithmetic/music/action planning, see: Fedorenko E, Varley R. Language and thought are not the same thing: evidence from neuroimaging and neurological patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Apr;1369(1):132-53. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13046. Contra domain-generality, Fedorenko and Varley present evidence that not all thought involves language, such that skills including arithmetic, solving complex problems, listening to music, thinking about other people’s mental states, and navigating in the world are still intact in patients with global aphasia (complete loss of language).

- A lot of detailed work is still necessary to identify the functional specialisation of areas within temporo-parietal cortex with respect to phonology, semantics, speech perception and speech production. Here’s one paper showing this painstaking work: Ekert JO, Gajardo-Vidal A, Lorca-Puls DL, Hope TMH, Dick F, Crinion JT, Green DW, Price CJ. Dissociating the functions of three left posterior superior temporal regions that contribute to speech perception and production. Neuroimage. 2021 Dec 15;245:118764. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118764.

The evolution of language

- ‘One of our favourite speculations is that the evolution of language was linked to the evolution of tool use.’ – For discussion of this idea and the proposal that gestural communication precedes oral communication in the evolution of language, see: Forrester GS, Rodriguez A. Slip of the tongue: Implications for evolution and language development. Cognition. 2015 Aug;141:103-11. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.04.012.

- ‘If you compare the structure of the vocal cords, these look different in humans compared to monkeys‘ – Vocal cords, these look different in humans compared to monkeys: Nishimura T, Tokuda IT, Miyachi S, Dunn JC, Herbst CT, Ishimura K, Kaneko A, Kinoshita Y, Koda H, Saers JPP, Imai H, Matsuda T, Larsen ON, Jürgens U, Hirabayashi H, Kojima S, Fitch WT. Evolutionary loss of complexity in human vocal anatomy as an adaptation for speech. Science. 2022 Aug 12;377(6607):760-763. doi: 10.1126/science.abm1574.

- ‘the arcuate fasciculus, connecting Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas … looks similar in humans and monkeys‘ – See: Becker Y, Loh KK, Coulon O, Meguerditchian A. The Arcuate Fasciculus and language origins: Disentangling existing conceptions that influence evolutionary accounts. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022 Mar;134:104490. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.12.013. See also: Balezeau F, Wilson B, Gallardo G, Dick F, Hopkins W, Anwander A, Friederici AD, Griffiths TD, Petkov CI. Primate auditory prototype in the evolution of the arcuate fasciculus. Nat Neurosci. 2020 May;23(5):611-614. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0623-9.

- Evolution may involve tweaking the wiring: This study shows that the cortical motor network for the larynx is similar across primates, but humans show additional connectivity from this system to sensory systems, which allows more accurate prediction and tuning of speech production: Veena Kumar, Paula L. Croxson, Kristina Simonyan (2016). Structural Organization of the Laryngeal Motor Cortical Network and Its Implication for Evolution of Speech Production. Journal of Neuroscience 13 April 2016, 36 (15) 4170-4181; DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3914-15.2016

- ‘the central nervous system … is sufficiently flexible that it can use the hands to produce language and vision to perceive language, using similar sensorimotor association cortex, in the form of sign language‘ – For the brain organisation of sign language, see: Trettenbrein PC, Papitto G, Friederici AD, Zaccarella E. Functional neuroanatomy of language without speech: An ALE meta-analysis of sign language. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021 Feb 15;42(3):699-712. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25254.

- ‘Why don’t other primates have our kind of language?‘ – Ah, gorillas, why have you failed to evolve human language? We asked this guy:

And then we invented reading

- One shouldn’t get hung up on reading as the perfect example of central nervous plasticity to cultural artefacts. Evolution doesn’t care, it doesn’t commit to specific computations. And the central nervous system doesn’t care, it adapts. Right now, sitting in your brain, there’s a sensorimotor system for using touchscreens and a detector for your mobile phone (probably not far away from the place where, in another life, you might have had a banana detector…)

- ‘an English learner is required to learn that p, b, d, and q are not the same object‘ – Mirror reversal errors in letter recognition while learning to read: Duñabeitia JA, Dimitropoulou M, Estévez A, Carreiras M. The influence of reading expertise in mirror-letter perception: Evidence from beginning and expert readers. Mind Brain Educ. 2013 Jun 1;7(2):10.1111/mbe.12017. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12017.

- ‘The left [hemisphere] kicks out face processing and comes to focus on recognising written words‘ – Reorganisation of left and right fusiform function visual object recognition function during reading acquisition: Dehaene S, Pegado F, Braga LW, Ventura P, Nunes Filho G, Jobert A, Dehaene-Lambertz G, Kolinsky R, Morais J, Cohen L. How learning to read changes the cortical networks for vision and language. Science. 2010 Dec 3;330(6009):1359-64. doi: 10.1126/science.1194140.

- For more on the neuroscience of reading, see Seidenberg, M. S. (2017). Language at the Speed of Sight: How We Read, Why So Many Can’t, and What Can Be Done About It, Basic Books. And DeHaene, S. (2010). Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read. Penguin Books.

Consciousness

- ‘We consider consciousness here … not because we think other animals don’t experience some form of consciousness … but because humans are the ones bragging about it‘ – For example, here’s what Max Plank, Nobel Prize-Winning German Physicist and Father of Quantum Theory, had to say: “I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.” Sounds like bragging to us.

- ‘We’re the ones taking the selfies‘ – Here’s the latest on why we take selfies: Niese, Z. A., Libby, L. K., & Eibach, R. P. (2023). Picturing Your Life: The Role of Imagery Perspective in Personal Photos. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506231163012

- ‘Our theories about the degree of consciousness in other animals feed into our moral views on how we should treat other species‘ – Regarding the moral consequences of consciousness, many don’t want to harm (let alone eat) life that is conscious, and believe that possession of consciousness conveys rights to a species: Mazor M, Brown S, Ciaunica A, Demertzi A, Fahrenfort J, Faivre N, Francken JC, Lamy D, Lenggenhager B, Moutoussis M, Nizzi MC, Salomon R, Soto D, Stein T, Lubianiker N. The Scientific Study of Consciousness Cannot and Should Not Be Morally Neutral. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2022 Sep 28:17456916221110222. doi: 10.1177/17456916221110222. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36170496.

- In Chapter 5, we used the example of the honeybee brain to demonstrate what level of computational power could be delivered by one million neurons. Here’s an article from the Washington Post proposing that those 1 million neurons are sufficient to support consciousness in bees and that sentience conveys ethical status. Text.

- Here’s some work considering conscious states of boredom in animals and their importance for thinking about animal welfare, for example in farming: Wemelsfelder, F. (1984). Animal boredom: Is a scientific study of the subjective experiences of animals possible? In M.W. Fox & L.D. Mickley (Eds.), Advances in animal welfare science 1984/85 (pp. 115-154). Washington, DC: The Humane Society of the United States.

- ‘Some view consciousness as the greatest current mystery in science‘ – Here’s an example: https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/consciousness-how-can-we-solve-the-greatest-mystery-in-science/

- ‘Others slice up the problem, identifying the easy part (the biological processes that underlie mental functions, like perception, memory, and attention) and the hard part (explaining subjective experience, why the operation of these biological processes should feel like anything)‘ – Here’s a paper drawing the distinction between the hard and easy parts of the problem: Chalmers D. 1995. Facing up to the hard problem of consciousness. J. Conscious. Stud. 2, 200–219. For more recent discussion, see: Dennett Daniel C. 2018 Facing up to the hard question of consciousness. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, 373, 2017034220170342. http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0342

- So if explaining the ‘what it feels like’ of consciousness is the hard part, come on then, tell us what the easy problems of consciousness are! Well, Daniel Dennett summarises some of them for us. Apparently, it is relatively easy to explain the following: the ability to discriminate, categorise and react to environmental stimuli; the integration of information by a cognitive system; the reportability of mental states; the ability of a system to access its own internal states; the focus of attention; the deliberate control of behaviour; the difference between wakefulness and sleep. Dennett also identifies another hard problem, which he thinks more pressing: once some item or content ‘enters consciousness’, what does this cause or enable or modify? Dennett DC. 2018 Facing up to the hard question of consciousness. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373: 20170342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0342

- ‘First we draw out the territory of possible explanations – you can pick your favourite‘ – Here’s a more formal version of the theoretical landscape of consciousness theories from some of our previous work: Atkinson, A.P., Thomas, M.S.C., & Cleeremans, A. (2000). Consciousness: Mapping the theoretical landscape. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4 (10), 372-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01533-3. Figure 1 from this paper was adapted into our Venn diagram.

- ‘If you don’t think consciousness is something magical, there are four kinds of ways you could explain it‘ – We don’t think consciousness is magical because it seems to vary systematically with the states of the brain. E.g., damage or stimulation to certain parts of the brain produces alterations in consciousness in predictable ways. But as you saw in our discussion of the predictive brain, we do like magic, too.

- ‘There have been various propositions‘ – Here are some references for proposals that consciousness arises as a function of integrating, sharing, or merely representing information (and one that it’s a quantum effect):

- Integrated Information Theory: Tononi, G., & Koch, G. Consciousness: Here, There and Everywhere? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Philosophical Transactions B, 370 (1668). 2015. Doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0167;

- Global Workspace Theory: Mashour, G. A., Roelfsema, P., Changeux, J-P., & Dehaene, S. (2020). Conscious Processing and the Global Neuronal Workspace Hypothesis. Neuron, Volume 105, Issue 5, 4 March 2020, Pages 776-798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.026;

- Higher-order thought: R. Brown, H. Lau, J.E. LeDoux (2019). Understanding the Higher-Order Approach to Consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci., 23 (2019), pp. 754-768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.06.009;

- Consciousness as a quantum effect: ‘Orchestrated objective reduction’: Stuart Hameroff (2021) ‘Orch OR’ is the most complete, and most easily falsifiable theory of consciousness, Cognitive Neuroscience, 12:2, 74-76, DOI: 10.1080/17588928.2020.1839037.

- ‘there could be cortical activation which doesn’t contribute to experience but anticipates it or is triggered by it‘ – The tricky part of deriving neural correlates of consciousness is identifying processes that precede or follow the experience such as selective attention, expectation, self-monitoring, unconscious stimulus processing, task planning and reporting. This argument is adapted from: Koch C, Massimini M, Boly M, Tononi G. Neural correlates of consciousness: progress and problems. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016 May;17(5):307-21. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.22. PMID: 27094080, p.308

- ‘Google says its chatbot is not sentient, but how do we tell?‘ – See: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/google-engineer-claims-ai-chatbot-is-sentient-why-that-matters/

- ‘[An illustrative proposal that] fits pretty well with current evidence’ – For that evidence, see: Koch C, Massimini M, Boly M, Tononi G. Neural correlates of consciousness: progress and problems. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016 May;17(5):307-21. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.22. PMID: 27094080.

- ‘consciousness is primarily associated with activity in the higher levels of the sensory hierarchies in the back of the brain‘ – Conscious only associated with upper levels of posterior sensory hierarchies: Koch, C. (2018). What is consciousness? Nature, 557, S8-S12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05097-x: Koch says: “curiously, the primary visual cortex that receives and passes on the information streaming up from the eyes does not signal what the subject sees. A similar hierarchy of labor appears to be true of sound and touch: primary auditory and primary somatosensory cortices do not directly contribute to the content of auditory or somatosensory experience. Instead it is the next stages of processing—in the posterior hot zone—that give rise to conscious perception.”

- ‘and not with activity in the frontal cortex, sub-cortical structures, or cerebellum‘ – Cerebellum doesn’t contribute to consciousness: Koch, C. (2018). What is consciousness? Nature, 557, S8-S12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05097-x. Some of the recent evidence that consciousness is not directly related to prefrontal cortex functioning: Omri Raccah, Ned Block and Kieran C.R. Fox (2020). Does the Prefrontal Cortex Play an Essential Role in Consciousness? Insights from Intracranial Electrical Stimulation of the Human Brain. Journal of Neuroscience 10 March 2021, 41 (10) 2076-2087; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1141-20.2020

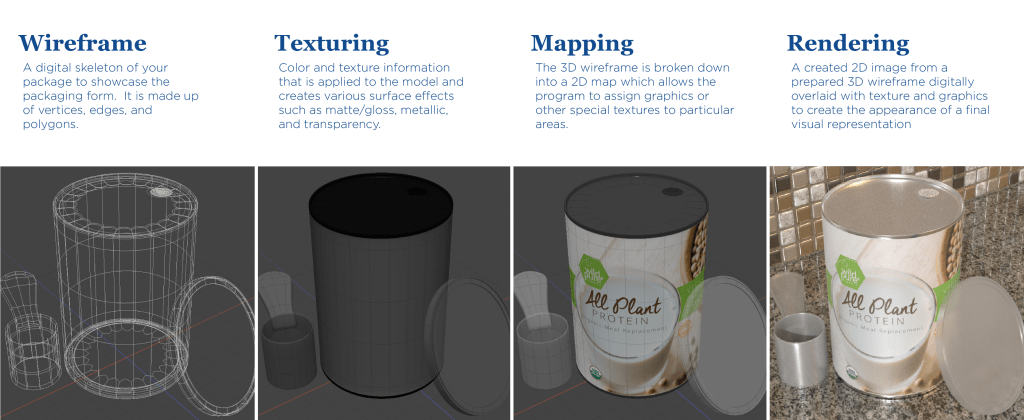

- ‘In video games that create photorealistic 3D worlds, the program generates the photorealistic images by a process called rendering or image synthesis‘ – Here’s an example of rendering (from here):

- ‘If you’re in a shoot-em-up game, your body may also be rendered, holding your proton ray gun out in front of you to zap the aliens‘ – Here’s an example of a video game where the body is rendered as part of the created 3D world:

- ‘If the model guesses wrong, that produces an illusion‘ – Visual illusions are meat and drink to consciousness researchers. In the sensory render theory, that’s because they are instances when the rendered 3D model of the world based on sensory input is wrong, so they reveal the 3D model-making process in action.

- ‘However, these systems may contribute content to the sensory render. For instance … limbic system activity may produce the sensation of a fast-beating heart and cold sweat, sensory information delivered from bodily organs modulated by limbic activity‘ – There are proposals that body sensations produced through emotions are key in driving decision making, as in Damasio’s somatic marker hypothesis: Damasio, Antonio R. (2008) [1994]. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4070-7206-7.

- ‘We know that the 3D model of the body is flexible. For example, the ‘bored’ bit of the 3D model that is left after limb amputation can get up to mischief and cause phantom limb sensations’ – Phantom limbs from somatosensory cortex plasticity: Hill A. Phantom limb pain: a review of the literature on attributes and potential mechanisms. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Feb;17(2):125-42. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00136-5. PMID: 10069153. Reshaping phantom limbs through mirror therapy: Kim, S. Y., & Kim, Y. Y. (2012). Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. The Korean journal of pain, 25(4), 272–274. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2012.25.4.272

- ‘we can be made to feel that we have extra body parts, such as a sixth finger‘ – Example of sixth finger illusion: Cadete, D., & Longo, M. (2022). The long sixth finger illusion: The representation of the supernumerary finger is not a copy and can be felt with varying lengths. Cognition, Volume 218, January 2022, 104948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104948

- ‘or even given a robot sixth finger to control‘ – Tamar Makin’s work at UCL suggests that the new extended body representation might alter how your original body is sensed, because there is only so much real estate in the brain to build the 3D model of the body. Sensations in new body parts might be at the expense of reducing sensations in your existing body. See: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2021/may/robotic-third-thumb-use-can-alter-brain-representation-hand

- ‘The limiting factor in expanding the conscious body would be the interface of the tool with the motor nervous system and sensory nervous system‘ – Here’s how things are going on neuron-computer chip interfaces, at least for playing video games: Kagan et al., In vitro neurons learn and exhibit sentience when embodied in a simulated game-world, Neuron (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2022.09.001

- Here’s another example of cutting-edge work, Daily Mail article “Bionic arm allows amputees to feel with fake fingers: Prosthetic combines intuitive motor control, touch and grip for the first time to create sensation of opening and closing a hand”. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-9947897/Bionic-arm-combines-intuitive-motor-control-touch-grip-time.html]

- Does the sensory render theory work for you as in illustrative example? You might find yourself asking: but why is this (sensory) bunch of neurons generating consciousness and not some others; or, who is it that’s observing the 3D sensory model of the world? If you’re asking those questions, then you’re back in the original ‘popcorn’ conceptualisation of consciousness: that the activity of some neurons will present conscious experience to an inner you, who’s watching life unfold on a movie screen while munching on a carton of popcorn. In the reconceptualisation, you’re no longer asking how the activity of the sensory part of the brain becomes conscious to ‘you’. Instead, you’re asking how the sensory part of the brain creates the world that is you, based on the physical stimulation the central nervous system receives from sensory neurons, themselves receiving electromagnetic, mechanical, or chemical stimulation from the body and world. The challenge (and this tells you a lot about what it feels like to work in consciousness research) – is this reconceptualisation a thinkable idea for you? Or does your mind resist, insisting instead that there’s got to be someone inside you, looking out at an independently existing world, because that’s the way it feels?

More gizmos

Tool use

- ‘One thing humans do exceptionally well is to build and use tools, to shape and interact with our physical world‘ – For more on the evolution of tool use, see Bracken, E., Billings, B.K., Barnes, M.J., Spocter, M.A. (2021). Evolution of Tool Use. In: Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_2948

- For recent work on archeological evidence of hominin tool use, and a comparison of tool use found in non-human primates today focusing on stone flakes, see: Harmand S, Arroyo A. Linking primatology and archaeology: The transversality of stone percussive behaviors. J Hum Evol. 2023 Aug;181:103398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103398. Epub 2023 Jun 15. PMID: 37329870. The authors conclude: “we argue that while it has been shown that extant primates can generate unintentional flakes, early hominins exhibited skills in the production and use of flakes not identified in primates.”

More power

- ‘What marks humans out is more conceptual power, which comes from larger brain size‘ – Greater brain size association with properties like tool use and cognitive control: Finlay BL, Uchiyama R. Developmental mechanisms channeling cortical evolution. Trends Neurosci. 2015 Feb;38(2):69-76. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.11.004. Epub 2014 Dec 11. PMID: 25497421.

- ‘For example, one study of primates found that the time an individual would wait for a preferred reward was correlated with absolute brain size‘ – See: Stevens JR. Evolutionary pressures on primate intertemporal choice. Proc Biol Sci. 2014 Jul 7;281(1786):20140499. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0499. PMID: 24827445; PMCID: PMC4046412.

- ‘Simply extending the duration of generating neurons during brain development may be the cause of human brain expansion‘ – See: Charvet CJ, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Variation in human brains may facilitate evolutionary change toward a limited range of phenotypes. Brain Behav Evol. 2013;81(2):74-85. doi: 10.1159/000345940. Epub 2013 Jan 25. PMID: 23363667; PMCID: PMC3658611.

- Larger brains take longer to develop, with implications for complex tool use: Heldstab SA, Isler K, Schuppli C, van Schaik CP. When ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny: Fixed neurodevelopmental sequence of manipulative skills among primates. Sci Adv. 2020 Jul 24;6(30):eabb4685. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb4685. PMID: 32754638; PMCID: PMC7380958. The authors argue: “complex foraging techniques therefore critically require a slow life history with low mortality, which explains the limited taxonomic distribution of flexible tool use and the unique elaboration of human technology”.

- ‘The mixing of limbic activity with concepts and social scripts in the cortex creates a wider palette of emotions‘ – See Mary Helen Immordino-Yang’s book on “Emotions, Learning and the Brain”, for an idea of how this works. For example, Chapter 9 covers admiration. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Emotions-Learning-Brain-Implications-Neuroscience/dp/0393709817

A clutch

- ‘The brain can even disengage while it carries out automatic activities. We can daydream about winning the lottery while we do the washing up’ – Here’s some functional brain imaging work on how one of the networks, the default mode network, is involved in depressing the clutch, thereby disengaging the brain from generating motor output in response to current sensory stimulation, and allowing daydreaming: Kucyi A, Davis KD. Dynamic functional connectivity of the default mode network tracks daydreaming. Neuroimage. 2014 Oct 15;100:471-80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.044. Epub 2014 Jun 25. PMID: 24973603.

Niche construction

- ‘Niche construction is the modification of components of the environment through an organism’s activities‘ – For an overview of the human specialism of niche construction, see Flynn, E.G., Laland, K.N., Kendal, R.L. and Kendal, J.R. (2013). Developmental niche construction. Dev Sci, 16: 296-313. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12030

No, this is simply not good enough

- ‘This brings us to a puzzle‘ – Mismatch of evolutionary increase in hominin brain size and cultural complexity: Howard-Jones, P.A. (2014), Evolutionary Perspectives on Mind, Brain, and Education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 8: 21-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12041

- ‘Some have even noted a possible decrease in human brain size since the end of the last Ice Age‘ – Recent decrease in human brain size and its explanation: DeSilva JM, Traniello JFA, Claxton AG and Fannin LD (2021). When and Why Did Human Brains Decrease in Size? A New Change-Point Analysis and Insights From Brain Evolution in Ants. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:742639. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.742639

- ‘The origin of cultural innovations is not obvious, and evidence of long periods of cultural stagnation across deep human history suggests innovation is not inevitable‘ – For current thinking into the explosion of cultural complexity in humans and what enabled it, see: Scerri EML, Will M. The revolution that still isn’t: The origins of behavioral complexity in Homo sapiens. J Hum Evol. 2023 Jun;179:103358. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103358. Epub 2023 Apr 13. PMID: 37058868. Scerri and Will say: “The behavioral origins of Homo sapiens can be traced back to the first material culture produced by our species in Africa, the Middle Stone Age (MSA). Beyond this broad consensus, the origins, patterns, and causes of behavioral complexity in modern humans remain debated … Instead of a continent-wide, gradual accumulation of complex material culture, the record exhibits a predominantly asynchronous presence and duration of many innovations across different regions of Africa. The emerging pattern of behavioral complexity from the MSA conforms to an intricate mosaic characterized by spatially discrete, temporally variable, and historically contingent trajectories. This archaeological record bears no direct relation to a simplistic shift in the human brain but rather reflects similar cognitive capacities that are variably manifested. The interaction of multiple causal factors constitutes the most parsimonious explanation driving the variable expression of complex behaviors, with demographic processes such as population structure, size, and connectivity playing a key role.”

- ‘Local conditions, therefore, may have been important in both the appearance and disappearance of symbolic behaviour in human populations, the accumulation of knowledge spiralling upwards or sputtering out in different cultures. Brain-wise, it could have been Neanderthals on the moon. Instead, Homo sapiens got lucky.’ – We asked Scarlet to sketch a cartoon to go with the idea of Neanderthals on the moon, but we couldn’t quite squeeze it in the book. Here it is for you.

Where does your mind stop?

- ‘So powerful are information tools that smartphones have even been pioneered as a strategy to support the everyday living skills of people who have experienced damage to their hippocampi‘ – Smart phone replaces the hippocampus: Svoboda E, Richards B. Compensating for anterograde amnesia: a new training method that capitalizes on emerging smartphone technologies. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009 Jul;15(4):629-38. doi: 10.1017/s1355617709090791. PMID: 19588540

- ‘What, then, marks the new boundaries of the mind?‘ – The boundaries of the extended mind and questions for philosophers: see Andy Clark’s book, see “Supersizing the Mind” (2010, Oxford University Press). https://www.amazon.co.uk/Supersizing-Embodiment-Cognitive-Extension-Philosophy/dp/0199773688

- ‘expert abacus users can also form a mental model of their abacus and use the model to carry out these calculations swiftly in their heads‘ – Brain imaging expert abacus users: Wang, C. (2020). A Review of the Effects of Abacus Training on Cognitive Functions and Neural Systems in Humans. Front. Neurosci. 14:913. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00913

- ‘For old people, [new information tools] may mark the collapse of society and the cultural decay of the youth of today‘ – Information tools and cultural decay of the youth of today: https://www.theguardian.com/science/head-quarters/2015/aug/13/susan-greenfield-bmj-editorial-digital-technology-video-games-need-less-shock-and-more-substance, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/11050871/Susan-Greenfield-Im-not-scaremongering.html. “With her new book Mind Change, Susan Greenfield collates scientific research on how digital technology affects our brains – but are her more worrying claims substantiated? The book recounts a familiar litany: links between video games and short attention spans, between social media use and social isolation…”

Upgrade Your Operating System

- ‘Deductive logic is an invention of culture that occurred only 2,500 years ago‘ – The historical invention of logic – see Michael Shenefelt and Heidi White’s book “If A then B: How the World Discovered Logic” (2013, Columbia University Press). https://www.amazon.co.uk/If-Then-World-Discovered-Logic/dp/0231161050/

- ‘in one study, participants were asked to derive valid deductive inferences for problems that stipulated erroneous facts about the world, while their brains were scanned‘ – Brain imaging of belief-conflicting logical problems: Houdé, O., and Borst, G. (2015). Evidence for an inhibitory-control theory of the reasoning brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9:148. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00148.

- More broadly, for the role of inhibitory control in learning counter-intuitive concepts, see: Mareschal, D. (2016). The neuroscience of conceptual learning in science and mathematics. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, Volume 10, August 2016, Pages 114-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.06.001

- ‘To show a contrast, here’s an example of reasoning from an adult who had not experienced such training‘ – The example of an apparent lack of logical deductive reasoning in an uneducated peasant from a remote area of the Soviet Union is quoted from: Luria, A. R. (1976). Cognitive development: Its cultural and social foundations. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. Pp. 108-109. Foreword. For further discussion, see Flynn J. R. (2009). What is Intelligence? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, chapter 2.

- There is an alternative view of this example, however, which is that it may represent the social context of the time, and the unequal power relations of scientists visiting from Moscow in 1930s Russia and rural peasants, rather than definite evidence of limits in deductive logic. Perhaps the peasant took the view that the scientist was asking trick questions, and when individuals in authority ask you trick questions, well perhaps the safest answer is to stick to what you know and have observed for yourself, as if you were in court. While Luria interpreted this peasant’s responses as demonstrating difficulty with hypothetical syllogistic reasoning as opposed to more concrete inferences in practical situations, difficulties typical of individuals whose cognitive abilities were formed by experience rather than by systematic instruction, for this particular example, the difference may have been less one of education than one of power. For more debate on this point, see this blog by Mark Liberman.

For the cool kids, the basic, the noobs, the geeks, the neeks and the nerds: How humans do hierarchies

- ‘Robert Sapolsky’s excellent work on social dominance in baboons‘ – Sapolsky, R. (2017). Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. Penguin Random House, London UK.

- ‘Let’s start with mice, who are another species that like a pecking order. One ingenious study traced the encoding of social rank to the mouse’s medial (middle) prefrontal cortex‘ – How social rank is encoded in the mouse brain: Padilla-Coreano, N., Batra, K., Patarino, M. et al. Cortical ensembles orchestrate social competition through hypothalamic outputs. Nature 603, 667–671 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04507-5

- ‘What about the human brain? Social dominance is equally salient to humans.’ – Neural mechanisms of social dominance in humans, see: Watanabe N and Yamamoto M (2015) Neural mechanisms of social dominance. Front. Neurosci. 9:154. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00154

- ‘This system is likely the place where social rank is played off against other demands in the system‘ – Social dominance learned through rewards and adverse experiences in striatum: Ligneul, R., & Dreher, J.-C. (2017). Social dominance representations in the human brain. In J.-C. Dreher & L. Tremblay (Eds.), Decision neuroscience: An integrative perspective (pp. 211–224). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805308-9.00017-8

- ‘a burst of testosterone marks a victory in a conflict‘ – Testosterone levels fluctuate as a function of the outcome of competitive interactions: Mazur, A. A biosocial model of status in face-to-face primate groups. Soc. Forces 64, 377–402 (1985). And: Batrinos ML. Testosterone and aggressive behavior in man. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Summer;10(3):563-8. doi: 10.5812/ijem.3661. Epub 2012 Jun 30. PMID: 23843821; PMCID: PMC3693622.

- ‘higher serotonin levels when you are among your people‘ – Serotonin levels depend on the social rank of monkeys in the presence of subordinates: Raleigh, M. J., McGuire, M. T., Brammer, G. L., and Yuwiler, A. (1984). Social and environmental influences on blood serotonin concentrations in monkeys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 41, 405–410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790150095013. For more recent work with humans on the involvement of serotonin in learning social ranks, see: Janet, R., Ligneul, R., Losecaat-Vermeer, A.B. et al. Regulation of social hierarchy learning by serotonin transporter availability. Neuropsychopharmacol. 47, 2205–2212 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-022-01378-2

- ‘The third human difference is that we have leaders‘ – For more on baboon social dominance hierarchies, human leaders, and limbic system influences on voting behaviour, see Chapter 12 in Sapolsky, R. (2017). Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. Penguin Random House, London UK.

- ‘around 40% of the differences we see in political leaning are heritable‘ – 40% heritability of political leanings from: Hatemi PK, Medland SE, Klemmensen R, Oskarsson S, Littvay L, Dawes CT, Verhulst B, McDermott R, Nørgaard AS, Klofstad CA, Christensen K, Johannesson M, Magnusson PK, Eaves LJ, Martin NG. Genetic influences on political ideologies: twin analyses of 19 measures of political ideologies from five democracies and genome-wide findings from three populations. Behav Genet. 2014 May;44(3):282-94. doi: 10.1007/s10519-014-9648-8. Epub 2014 Feb 26. PMID: 24569950; PMCID: PMC4038932. These genetic influences are, as we have seen, polygenic: lots of small contributions from many genetic variants. There is no ‘political gene’; a single gene or small group of genes does not directly influence ideological preferences. Rather, there are many subtle influences on the tuning of cortical, limbic, and reward systems which when exposed to the vagaries of life lead to the development of political leanings. The authors say: “Yet, it appears once ideological orientations become instantiated by some function of genetic disposition, environmental stimulus or epigenetic process, the psychological mechanisms that guide behavior in predictable ways appear somewhat stable and this stability appears to be related to genetic disposition. Thus, future studies that identify genetic and environmental pathways by which genes influence the regulation of hormonal, cognitive and emotive states, which in turn influences the selection into, interpretation of, and reaction to, environmental stimuli relevant to political values, may eventually provide the necessary glue to combine the multitude of neurobiological influences on ideology captured across the sciences.”

Box 9.1

- For more on the ethics of cognitive enhancement, see: Roskies, A. (2021) Neuroethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Metaphysics Research Laboratory, Stanford University

Box 9.2

- For more on the big questions in neuroethics, see: Fuchs T. Ethical issues in neuroscience. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;19(6):600-7. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000245752.75879.26. PMID: 17012939.